Arsenal (1929): Ukraine in Revolution

Introduction |Zvenyhora (1928) | Arsenal (1929) | Earth (1930) | Conclusions

Filmography | Earth Chronology | Bibliographies | Contact

|

|

Rrrrevolution to rrrecord it you rrrequire Thrrree ‘rrri’ - ‘rrri’ So the Hurrricane Rrroarrrs from the arrrbourrrs and the windstorrrms shrrriek.

|

||

|

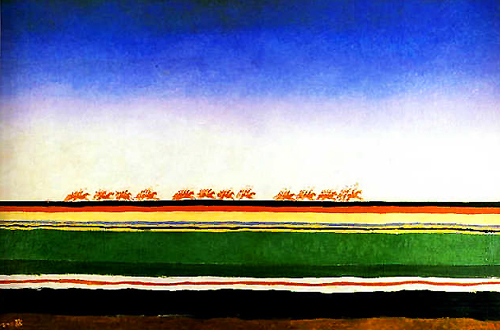

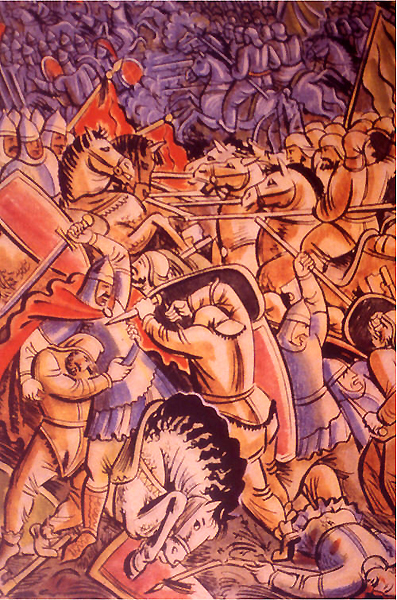

Kazimir Malevich, Red Cavalry

Riding, Kyiv (1918)

|

While Arsenal does not possess the same historical breadth as Zvenyhora, it does follow Zvenyhora in having the same seven part episodic division. In the film’s opening titles, Dovzhenko defines the film as a “Historical-Epic”. Because the film seems to cause so much narrative confusion [111], a brief description and summary of the events and figures portrayed will be given from the outset before venturing into more turbulent waters.

Episode One: During the spring of 1917, an emaciated village mother stands alone in her dilapidated cottage. Populated by cripples and World War I’s amputees, the village is largely deserted. Later, the woman attempts to sow seeds while her sons, World War I soldiers on a train, journey to the front. Oblivious to current events, Tsar Nicholas writes a letter in St. Petersburg. In desperation, a mother beats her children while a villager beats his horse. Enigmatic soldiers fight on ill-defined fronts in silhouette. Armies cross lines. A German soldier is driven to insanity by laughing gas.

Episode Two: The Train of revolution: attempting to hijack a train filled with soldiers returning from World War I, a group of haidamaks from Ukraine’s national army confronts the film’s hero. Preventing the hijacking with a show of machine-gun diplomacy, the train continues. Despite the engineer’s reservations, the train journeys down a steep grade and crashes. Rising from the wreckage is a demobilized former arsenal worker and soldier, Tymish Stoyan. Returning to his Kyiv arsenal factory for work, the director questions Tymish: “Who are you? A Ukrainian? A deserter?”

Tymish answers: A demobilized soldier - an arsenal worker.

Episode Three: Tymish witnesses the proclamation of an independent republic coinciding with Easter. Tymish views the proclamation in Kyiv of a Free Ukraine and the reading of the ‘first Universal’ in a mass gathering and parade in St. Sophia Square. Demobilized soldiers sign up for Petliura’s army; Tymish withholds signature.

Episode Four: Representing the Bolsheviks, Tymish attends the first congress of the Ukrainian national government in Kyiv. While the small Bolshevik group is outnumbered, their opinion is in alignment with a telegram that interrupts the congress from the Black Sea Fleet. Tymish's’ group of Bolsheviks leave the congress. Segments of the larger population are pictured supporting the ‘workers’ cause.

Episode Five: Various segments of society wait to see what will transpire in the country. The proletariat sabotage trains. The Kyiv bourgeoisie confer on which way to proceed. Groupings of people are paralyzed in their next course of action.

Episode Six: Carrying one of their comrades for burial to his mother, Red partisans on horseback gallop through the winter countryside outside Kyiv. horses converse during the 1918 winter. The arsenal uprising continues. A tank called ‘free Ukraine’ roams the Kyiv streets. An older nationalist confronts his Bolshevik student in a strange student/teacher Oedipal confrontation.

Episode Seven: In the uprising’s seventy-second hour, the arsenal workers launch their final offense. Confronted by the nationalist forces, Tymish realizes his machine gun is out of bullets. He makes his final stand. Announcing himself as a ‘Ukrainian worker’, the nationalists fire on him. He is unkillable and continues standing.

(Arsenal (1929): Full Movie, 88 minutes)

| Arsenal begins where Zvenyhora breaks off. It covers the soldiers’ mass defection from World War I in early 1917, the proclamation of independent Ukraine, the brief reign of the national government (Central Rada), and ends with the failed Kiev Bolshevik arsenal uprising in January 1918.[112] White, Red, Anarchist, Nationalist, American, German, Polish or even Austro-Hungarian histories all construct different accounts of these events. Usually, one version’s constructed narrative centre becomes footnote in another. |

|

|

|

Arsenal Poster

(1929)

|

In his work on the Formation of the Soviet Union, Harvard historian, Richard Pipes, characterizes the complexity of this period thus:

In Kiev itself governments came and went, edicts were issued, cabinet crises were resolved, diplomatic talks were carried on - but the rest of the country lived its own existence where the only effective regime was that of the gun. . .The Communists, who all along anxiously watched the developments there and did everything in their power to seize control for themselves, fared no better than did their Ukrainian nationalist and White Russian competitors.[113]

|

Ukraine became a common territorial battleground for competing nation states and later, historical narratives. In another silent Hollywood film during this period, emigré director, Maurice Stiller, titled Ukraine in this interval, The Hotel Imperial (1927). The film's European Title Hotel Stadt Lemberg referred to Western Ukraine's Lviv's various occupied national identities (Lviv, Lvov, Lemberg.) | ||

| Hotel Imperial Poster (1927) | |||

As in Pudovkin’s Mother (1926), the issue of identity and the development of a social-political consciousness is at the centre of Arsenal. Unlike Pudovkin’s film, the identity of Dovzhenko’s soldier has wider political implications. Dovzhenko plays on the oft-cited notion: whosoever controls the soldier and army’s loyalty controls the larger nation[114] . Presenting a condensed symbolic visualization from the perspective of a demobilized soldier, Dovzhenko figures the events of World War I, the revolution, the rise of the Ukrainian National republic and the failed Kyiv Arsenal uprising.

In an essay on the Communist Party of Ukraine and its role in the Ukrainian Revolution, John S. Reshetar, Jr. characterized the micrologic historical event Dovzhenko chooses to figure thus:

The Bolsheviks who remained in Kiev attempted an armed uprising to overthrow the Rada (Ukrainian National Government) in late January 1918. Basing themselves primarily on the Kiev Arsenal, the local Bolsheviks succeeded in waging street warfare against the forces of the Rada from January 29 to February 2. Aided principally by Russian railroad workers, the Kiev Bolsheviks were unable to overthrow the Rada. The Rada’s forces in the city which included many students, numbered six to eight thousand, while the Bolsheviks claimed that they had four to five thousand. The Rada retained control of the telephone system, had greater mobility, and had the services of many trained army officers as well as aid of Ukrainian sailors from the Black Sea fleet. By February 2 and 3, the Bolshevik insurgents were besieged in the Arsenal and were compelled to surrender when Ukrainian forces under the command of Symon Petliura arrived in the city and deployed artillery. Petliura’s forces had retreated from the area northeast of Kiev, where they had been resisting the advancing Russian forces. It is evident that the local Bolsheviks could not themselves have overthrown the Rada, but their uprising in Kiev did weaken the defense of the city and aid the Russian invader. On February 7, after several days of fighting, Murayev’s forces succeeded in establishing themselves in Kiev, although sporadic fighting continued for several days.[115]

| As Eisenstein did in Battleship Potempkin (1925), Dovzhenko appropriates this historical incident to his own purpose. Unlike Eisenstein and to the consternation of contemporary Soviet critics, the historical Arsenal does not become a central episode in the film. Unlike the dominant presentations of the Russian Revolution of 1917, the revolution portrayed in Arsenal is presented only as secondarily socio-economic. In Dovzhenko’s visualization, the conflict centrally regards the country’s national aspirations. |

|

||

|

Poster for Eisenstein's Battleship

Potempkin (1925)

|

|||

Contemporary Ukrainian review would paint an equivocal picture of Arsenal. While people like the symbolist, Yakiv Savchenko, presented sympathetic analyses[116], a denunciatory critique was launched by the journal Komsomolets Ukrainy (Communist Youth Association of Ukraine). On December 21, 1928, a couple of months before Arsenal’s official premiere and release, articles such as “False Arsenal” and “Rather than an Epic - A Farce” were printed to prevent Arsenal’s distribution[117]. This early contemporary denunciation by fellow members of the Ukrainian avant-garde is interesting not so much for its devaluation but for the published reasons of censure and commentary as to why official party publishing umbrellas (Komsomolets Ukrainy) felt Arsenal to be ‘un-Soviet’. It also provides some different early opinions regarding the film. The attack on Arsenal would be led by Semyon Getz, who would later publish a similar Russian denunciation in Zhizn iskusstva on April 2, 1929. In his Ukrainian variant Getz would write:

Dovzhenko is a wonderful artist but his far seeing talent and film qualifications lack one thing: a feeling for the proportionality of the exposition. . .either Dovzhenko wanted only to turnover the glorious page from the past Arsenal - if so, he should have built the entire scenario around it. Or he gave himself the serious task of relaying all the grand events of the beginnings of the October revolution - if so he is right in producing such a wide-reaching exposition. But let’s not argue about which path is more believable but leave it with the conclusion that the historic Arsenal suffered considerably from this mode of composition. . .From whence comes such pessimism?[118]

Getz is correct in his conjecture. Unlike Eisenstein’s Strike (1924) or Battleship Potemkin, the historic Kyiv arsenal uprising does not form the centrepiece of Arsenal but is marginalized and appropriated to ‘other’ purposes.

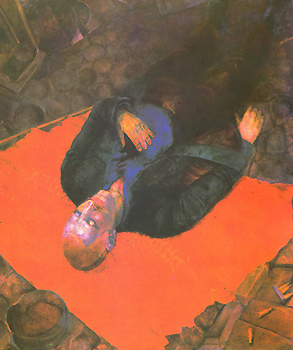

Diego Rivera's In the Arsenal Factory (1928), Frieda Kahlo Hands out Arms

Unlike Eisenstein’s Potemkin or Diego Rivera's celebratory painterly tribute to the historical incident Dovzhenko's Arsenal presents to say the least an ambivalent and, as Getz puts it, ‘pessimistic’ picture of the historic event. Apart from Getz, the rest of Komsomolets Ukrainy‘s denunciations were ironically enlisted from well-known former VAPLITE members and the Ukrainian avant-garde. Kino editor, Mykola Bazhan’s, denunciation of the film was at best half-hearted. “Against Arsenal, it’s not made in a mathematical method; against Arsenal, you won’t be able to see, the abstraction of mediocre people through professonial statistics.” [119] Valerian Polischuk commented, “Arsenal gave us altogether not what might have been expected. Rather than aesthetic beauty, Dovzhenko gave us a fraudulent depiction”. The futurist filmmaker, Berezil theatre associate director and Dovzhenko’s collaborator and director for his screenplay, Vasia the Reformer (1926), Faust Lopatynsky would write:

In the first place, for the February Revolution in Ukraine Dovzhenko substituted an operetta of the Central Rada’s (Ukrainian National Government) last days and existence . . .Second Error: Dovzhenko chose to totally ignore those social economic facts that would explain the further struggle between the national movement and the social revolution. These two cardinal errors do not belong within the film. To my mind, without first and foremost correcting them ( as well as other smaller ones), a trace of this picture should not be allowed on screens”.[120]

Why did the Ukrainian avant-garde write against Dovzhenko? Were the writers, fellow Vaplitians and colleagues denouncing Dovzhenko and later sending a writers’ delegation with a petition against the film to Moscow and Stalin of their own volition? Later commentators[121] and Dovzhenko himself all hold differing opinions regarding this Arsenal-inspired debacle. Dovzhenko comments in his 1939 biography:

Although I was not surprised by the reception Arsenal was given, I was oppressed by it. The film was accepted and understood by the people and the Party but not by the writer’s community, or, one must suppose, the higher Ukrainian leadership. For betraying “Mother Ukraine”, for profaning the Ukrainian nation and intelligentsia, for depicting the Ukrainian nationalists as provincial nonentities and adventurers, and so forth, the film was reviled in the press; I was boycotted for many years, and the leadership treated me for a long time with a cool reserve that I could not comprehend. In any case, the delegation of writers that travelled to Moscow with a protest and a demand to ban the film was not reproached by the leadership.[122]

The dominant ‘opinion’ of Arsenal in the West was that Arsenal was made ‘In the Service of the State’[123] . The western critics who look at Arsenal take as their optic a passage from Dovzhenko’s 1939 autobiography[124]. The passage reads:

In my next film, Arsenal, I considerably narrowed the range of my cinematic goals. The assignment to make the film was entirely political, set by the Party. [125]

|

Used to link Arsenal with Eisenstein’s October (1927), Pudovkin’s End of St. Petersburg (1927) and Schub’s Fall of the Romanoff Dynasty (1927), this passage guides western and post 1931 ‘Soviet’ readings of Arsenal and, it is not unfair to say, the placement of Dovzhenko. | ||

|

French Poster for October

(1927)

|

Prescribed as a condition for his re-application for CP(B)U membership, Dovzhenko’s 1939 auto-biography from which the above passage is taken was written as a public apologia. This work’s intended audience was an official ‘party’ audience. The Stalinist terror had been running in gear for several years. Ukraine had suffered a famine which had killed a quarter of the population. The intelligentsia had been decimated. Most of the figures of the cultural renaissance had been silenced. Those with an international reputation had been forced into internal exile from their own republics (Dovzhenko to Moscow). The former members of Ukraine’s cultural renaissance who were producing creative work had been ‘brought to a correct ideological understanding’ and were publishing Stalinist panegyric[127].

The passage’s original English translator, Marco Carynnyk, made a comparison with the original holograph, showing that the Soviet editor’s project had large western resonance.[128] Throughout the text of Dovzhenko’s already self-censored autobiographical statements, sentences are cut, pasted out of context, edited, deleted and reworked towards a stronger ideologic viewpoint.[129] Translated in the West, this ideologically revamped autobiography was read, more often than not, without context. Cited by western critics, the above passage placed Dovzhenko into an established line.

|

||

|

Victor Palmov (ARMU), May

Day, 1929, oil on canvas, Kyiv

|

Forms

In terms of genre, Arsenal begins with an announcement of its title and the subheading “a Historic Revolutionary Epic”. Like Zvenyhora, Dovzhenko begins with the form of the classic poetic epic. Zvenyhora moved towards comedy and Menippean satire. Arsenal moves towards funereal lament and tragedy. Finding its roots in a regional variant of the oral and musical form of the epic, the type of poetic epic Dovzhenko references in Arsenal is ‘the duma’ or traditional Ukrainian oral lament. The search for new forms, often transposed from other media, was common in early slavic modernism which drew on musical forms. Olha Kobylyanska’s “Impromptu Phantasie”, Mykhailo Kotsiubinsky’s “Intermezzo”, or the Russian modernist, Andrei Belyi’s fascination with musicology and earlier realist antecedent in stories such as Tolstoy’s “Kreutzer Sonata” can serve as examples.

One of Dovzhenko’s early contemporary critics, the symbolist poet, Yakiv Savchenko, grappled with Arsenal’s generic innovation:

From the perspective of traditional ‘thematics’, ‘suzhet’ etc., Arsenal doesn’t open itself up to satisfactory understanding: the film walks past the borders of such terminology: it’s deeper and with more substance than these terms encompass. . .First of all, if we want to delineate genre, the one that Arsenal opens, we could benefit from literary terms: this - in terms of tone - is the ballad, poem, or ‘duma’ but, for the country, saturated with the psychology of our times.[130]

|

The “duma” was a lyric historical-epic musical oral form of folk origin. Originating as a cossack epos, ‘the duma’ emerged in the seventeenth century as quasi-heroic song sung by wandering blind “kobzars” playing either “kobza”, “bandura” or “lira” (hurdy-gurdy). Visualized earlier as a motif in his silent trilogy at Zvenyhora’s beginning, this traditional folk form was revitalized by nineteenth-century Romantics like Kostomarov, Kulish and Shevchenko[131]. In Dovzhenko’s time this interest in the duma was rekindled through a second wave of interest in ethnography[132]. Throughout Arsenal Dovzhenko references the thirty well-known dumas.[133] |

||

|

Blind Kobzar, Ukraine,

1918

|

|||

Through the rhythms of montage, visual rhyme, but also an application of ‘choreographic’ and choric structure, Dovzhenko visually plays on the duma’s musical phrasing. The dumas did not have a set strophic form but consisted of uneven segments, each of which constituted a syntactic whole. Arsenal echoes this strophic structure, each of the episodes uneven in length but embodying a syntactic whole.

A peasant’s lamentable situation is figured in Arsenal’s opening through a village mother sowing grain alone without the help of her sons. She falls in the fields in a rhythmic funereal ‘duma’-like visualization. Contextually referencing historical dumas, Dovzhenko’s ‘choric’ intent is also on the level of form. In the later biography and memoirs of Dovzhenko’s long-time collaborator, the cinematographer of Arsenal, Earth and Ivan, Danylo Demutsky notes:

Arsenal’s opening episode was thought of by Dovzhenko as the introductory canto or introductory verse of the film. Like the lyric intonation of the ancient Ukrainian dumy, it served as an epic introduction. For his imagined embodiment, it was absolutely indispensable to know the rhythm of the women’s movements and correspond those rhythms with that of the duma. . . .more than once Oleksander Petrovich (Dovzhenko) compelled the aged woman to sow the grain in front of the camera, and I, at this time, quietly sung to myself the measures of a duma which I knew looking through the viewfinder so the woman’s movements were choreographed with the duma’s rhythm.[134]

By the time he went to work for Dovzhenko as cinematographer, Demutsky (1893-1954) was already known as an avant-garde photographer. He had acted as cinematographer on Staboviy’s Two Days (1927) and previously with Dovzhenko on Vasia the Reformer (1926). Demutsky would also collaborate with Dovzhenko on his next projects Earth and Ivan. In June of 1927, VUFKU’s KINO had profiled Demutsky, speaking about his exhibitions and awards in Paris for his “Photo-Impressionism”[135].

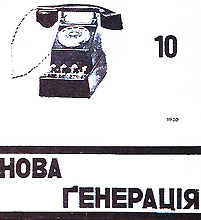

| Concurrent with Arsenal’s release, Semenko’s Futurist Journal Nova Heneratsiia would profile stills from Demutsky’s Arsenal cinematography in a comparative perspective with the Hungarian modernist, Moholy Nagy[136]. Stills from Arsenal would also be exhibited in a fine arts context in the photography section of the Second Exhibition of Soviet Ukrainian Artists, which would travel through Ukraine in 1929[137]. |

|

||

|

Futurist Journal New

Generation

|

|||

Connected with the Renaissance and part of ARMU, Demutsky’s background was much in alignment with Dovzhenko’s aesthetic prescriptions in his “On the Problems of the Visual Arts”. Like the rest of the team Dovzhenko was assembling during the silent trilogy, Demutsky had an international European ‘aesthetic’ orientation.

The ‘duma’ connection is larger than has been allowed. Demutsky’s father, Porfyr, had been one of folklore’s early ethnographers,[138] recording more than one thousand folk songs and collecting Ukrainian dumy. Porphyr Demutsky was a member of the ethnographic Commission of the Academy of Sciences of Ukrainian SSR, had published investigations on the characteristics of polyphony, Bahatoholossia, Narodni Ukrainski Pisni v Kyivschyni (Ukrainian Folk Songs in the Kiev Region, 2 vols., 1905-1907 and examinations of the duma or genre of epic lament, Lyra ta ii motyvy (The Lyre and Its Motifs, Kyiv, 1903).

Kobzars Gathering, Kharkiv, 1911, note both 'lyra' and 'bandura'

In 1939 Stalin brought together Ukraine’s remaining blind duma playing ‘kobzars’ and ‘lyra” singers for a concert, conference and gathering. After the concert, he had them shot [139]. In the suppression, destruction, bowdlerization and censorship of ‘duma’ collections (i.e. Kateryna Hrushevska, Porphyr Demutsky) and silencing of these cultural treasures, the politically resistive nature that this folk epic posed to the Soviet regime is evident.

Dovzhenko’s interest in folk music dates back to his school days at the Hlukhiv Academy. His writings, novelettes and short stories[140] extensively quote folk lyric and later he was to write essays on characteristics of “the Ukrainian Folk Song” [141]. Demutsky would work closely with Dovzhenko both on Zemlya (1930) and Ivan, contributing to what has been called Dovzhenko’s ‘poetic’ or lyric style. Like much of the team that worked on the silent trilogy, he would also be exiled to Central Asia and was only partially rehabilitated after the Second World War.

| Dovzhenko consciously and politically constructed his ‘filmmaking team’. Through a planned ‘collective creativity’, he synthesized and drew from the cultural renaissance’s leading groups. Punning on a current novel by Ukrainian neo-romantic writer, Yuri Yanovsky (Maistr Korablia, Master of the Ship, 1928) in which the young Dovzhenko figures as the main character, Yakiv Savchenko, would comment about Dovzhenko as a “Maister Syntezy” (Master of Synthesis)[142]. Savchenko would also similarly speak about Dovzhenko’s drawing from the cultural renaissance as a larger project of fulfilling early cinema’s ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ (work of total art) synthetic ambitions. In later lectures at the Moscow Film School, VGIK, Dovzhenko would discourse on cinema as a syncretic aesthetic. |

|

||

|

Bookcover for Yuri

Yanovsky's "Master of the Ship" (1928)

|

|||

The cinema itself is an aesthetic of synthesis. It takes to itself elements of literature, short-stories, novels, and plays. The majority of cinematic works are closer to drama than to the novel but cinema integrates elements of theatre, fine art and music.[143]

Dovzhenko’s draws on the choric and ‘peoples’’ (narodny) folk form of the ‘duma’ with its anonymous oral folk form and polyglossia. The notions being articulated are what would historically have resonance later as socio-semiotics (i.e. Bakhtinian: polyphony, polyglossia, choric). In Arsenal these notions would be worked out in a unique cultural synaesthesia through the folk song and ‘duma’. Oral folk models of the epic ‘dumy’ would be foregrounded in a peculiarly modernist, Marxist and collective model of aesthetic production. In a line from Krychevsky, Demutsky, Khvylovy and Vaplite’s polemics, Berezil’s actors and other figures who shall be mentioned, Dovzhenko’s aesthetic and political agenda constructed a polyphonic or many-voiced creativity orientated towards a Western European modernism and a rearticulation of traditional folk forms.

At the heart of Arsenal is the question of ‘identity’ and ‘national consciousness’. Through a duma-like visualization, Arsenal traces this development in one of the film’s central characters, the demobilized World War I soldier. Questions as to whether Dovzhenko is attempting to consciously ‘deconstruct’ the genre, work at odds with one of its historic purposes or, subversively, create another level of dialectic in Arsenal’s larger meaning are open for investigation. As Arsenal progresses, this question of genre as strategy of political resistance or cooptation will become important as to how to ‘read’ the aesthetic.

Dovzhenko references this lamentory aspect of the duma genre from Arsenal’s beginning through naming the genre “historo-poetic epic” and Arsenal’s opening inter-titles:

“Oi Bulo v Materi try syny”.

Bula Viyna

Nema v materi syny.

“Oy, there was a mother with three sons.

There was a War.

The mother’s sons are no more”.[144]

By working in this genre of lament, Dovzhenko questions and comments on borders of the Bolshevik prescription ‘national in form and socialist in content.” Dovzhenko visualizes the traditional conventions of lament of the musico-literary oral folk ‘dumy’ genre but also reconfigures the genre saturating his visual duma with the psychology of contemporary times. Through a modernist visualization of this historic epic in silent cinema, Arsenal’s aesthetic acts as a limit ground and border case of the above Bolshevik internationalist prescription. Dovzhenko’s working method is a Hegelian-inspired philosophic Marxist form of argumentation: taking a thesis, ‘national in form, socialist in content’, pitting it against its antithesis, the ‘duma’, where the form and content is tied to a national orientation, and testing this through the synthesis of the two within the produced material document - Arsenal.

Contemporaneous to Dovzhenko, the closest twentieth century literary analogue working along the same lines as Dovzhenko is the Ukrainian poet, Pavlo Tychyna. Tychyna also took up the traditional folk ballad and reconfigured it in modernist variant. In his poem, “Three Sons”, Tychyna writes:

|

Three Sons came home to see their mother: Three soldier-sons unlike each other One the poor defended One the rich attended The last would lend his strength to no one, free: A bandit, he.[145] |

||

|

Cover for Tychyna's Wind from Ukraine. Cover Design by Dovzhenko's earlier set designer Vasyl Krychevsky |

Like

Arsenal, Tychyna’s ‘Try Syny” figures the situation after World

War I through a reconfiguring of traditional folk form and three sons

gone to war. To figure the upheaval, anarchic conditions and tragedy

of the times, both Tychyna and Dovzhenko liberate traditional forms by

reconfiguring the well-known “duma”, “About the Widow and Her Three

Sons”[146].

|

The traditional duma from which both figures draw begins:

Oh, on Sunday, early in the morning Very early, at the time of twilight, It was not the pine forest rustling, And it was not the green glade talking with the wind, It was a poor widow, an old woman, Pale as the turtle dove, Speaking to her children, the widow’s sons. She had three sons, Bright as young falcons, And she raised them from a young age to maturity And she did not send them to work as hired hands, She did not let strangers abuse them, She was hoping to achieve fame and glory through them, She was hoping to live with them throughout her declining years.[147] |

|

||

| Blind Kobzar with guide, Ukraine, 1915 |

In Dovzhenko’s reconfiguration, the widow’s three sons become villagers mobilized to World War I. Visualizing the heads of three sleeping soldiers in sheepskin caps, Dovzhenko portrays the young sons as lambs led to the slaughter. Inter-titles read, “And the woman had no sons”. The three sons succumb to war’s fatalities and the film opens with the mother’s lament. Alone, the mother’s tragedy and fate is figured through her sowing and fall in the fields. The original duma figures the mother’s tragedy thus:

She fell to the ground

She shed copious tears

She stood on her knees before God.

“Oh my sons, my young children,

How I worried and worried over you,

And look what I have gotten from you in return!

Where am I supposed to go now to await death?

Where am I supposed to rest my head now?[148]

| In Dovzhenko’s variant, the woman rests her head on the earth, fallen, fetally positioned, clinging to the earth. In the duma, the mother’s grief becomes a morality play because of the sons’ abandonment. In Dovzhenko’s re-articulation, the sons’ abandonment is due to their World War I mobilization. |

|

|

|

Still from Arsenal's

Fallen Mother (1929)

|

||

Film Poetry, Anarchy, Iconology

The creation of new artistic forms is always a complex transformation of old forms under the influence of new factors that have arisen in the environment that lies outside art.

(Dovzhenko, Vaplite: First Notebook, 1926)[149]

Tychyna’s “Three Sons” allegorically figures each of the sons presenting competing forces during this period of revolution and civil war - the nationalists, the communists and the anarchists. In Dovzhenko’s conceit none of these forces are presented as victors. The anarchic political voice is woven into the film form in what has been called Arsenal’s anarchic image juxtaposition.

During the historic period that Dovzhenko figures, Ukraine is subject to Europe’s largest twentieth century ‘anarchist’ manifestion. On this historical situation Orest Subtelny comments:

In 1919 total chaos engulfed Ukraine. Indeed, in the modern history of Europe no country experienced such complete anarchy, bitter civil strife, and total collapse of authority as did Ukraine at this time. Six different armies - those of the Ukrainians, the Bolsheviks, the Whites, the Entente, the Poles, and the anarchists - operated on its territory. Kyiv changed hands five times in less than a year. Cities and regions were cut off from each other by numerous fronts. Communications with the outside world broke down almost completely. The starving cities emptied as people moved into the countryside in their search for food. Villages literally barricaded themselves against intruders and strangers. Meanwhile, the various governments that momentarily managed to establish themselves in Kyiv devoted most of their attention and energy to fending off the onslaughts of their enemies. Ukraine was a land easy to conquer but almost impossible to rule.[150]. . .Isolated from each other and the rest of the world, during this historical juncture, Ukraine’s previously ‘imperially’ subdivided territories fell apart into innumerable regions. Variously holding the power balance in Ukraine, the violent and preferred largest ‘stateless’ anarcho-polito movement, led by Nestor Makhno, Matvii Hryhoriv and an estimated 35,000 peasants, based itself out of Huliai Pole and variously moved in and out of Kyiv[151].

In Arsenal, Dovzhenko foregrounds an ‘aesthetic of anarchy’. Contemporaneously writing about Arsenal, Eisenstein commented on this anarchy as a rearticulation of film form: “The liberation of the whole action from the definition of time and space. . .a dramaturgy of the visual film form”[152].

In Culture and Imperialism Edward Said suggests that ‘nation states’ and ‘imperiums’ themselves are ‘narratives’ and ‘fictions’ with their own structured ‘mythologies’[153]. Said suggests a correlation between the nineteenth century realist narrative and a culture of imperialism. Dovzhenko figures an avant-garde liberation against this type of formal imperial correlative. In terms of film form, Arsenal’s thrust is against the ‘three act narrative structure’. In a contemporary review (1929), Eisenstein would comment about Arsenal , “I do not think there will be any students of this genre either. Perhaps this is one of the consumer faults in a planned economy”.[154] Eisenstein’s valorization makes a connection between a cultural superstructure and a certain type of ascendant economic base, now at variance with Dovzhenko’s aesthetic. Significantly, in 1929, Eisenstein places Arsenal’s form in alignment with the revolution’s utopian aspirations.

|

In a line from the ancient Slavic ‘war’ chronicle, Arsenal introduces a funereal ‘song’ or lament. Instead of following the traditional heroic deeds of the last Tsar or Nicholas II, Dovzhenko works against ‘war chronicle’ genre convention. Portraying the last Tsar of the Romanov dynasty not through heroic deeds or tragedy but through irony and satire, Arsenal follows a demobilized soldier. | ||

|

Photograph of Tsar Nicholas

II

|

In terms of the war film, the closest contemporary reference, other than Russian revolutionary portrayal, is the French avant-garde and Abel Gance’s epic, Napoleon (1925-27). In a brief scene where the soldiers return to their countries, Dovzhenko reflexively pays homage to Napoleon, a French soldier returning to his now pregnant wife, a bust of Napoleon adorning the background. Significantly, the Napoleons here are relegated to background busts. Dovzhenko’s foreground follows demobilized soldiers.

At the time of Arsenal’s release and in the same issue devoted to the film, VUFKU’s KINO would publish a longer feature on the war film mentioning William Wellman’s Wings (1927), King Vidor’s The Big Parade (1925), Les Kurbas’s now lost adaptation of Upton Sinclair’s Jimmie Higgins (1928) and the French Leon Poiret’s Verdunne [155]. Working against conventional ‘war’ film or battle chronicle convention, one of the repeated comments of contemporary reviewers surrounding Arsenal would be that for a ‘war’ film, Arsenal shows a lack of war or battle scenes. Appropriating the war film genre for other thematic purposes, Arsenal has closer affinities with the ancient Slavic battle chronicle, ‘Song of Igor’s Campaign’.

|

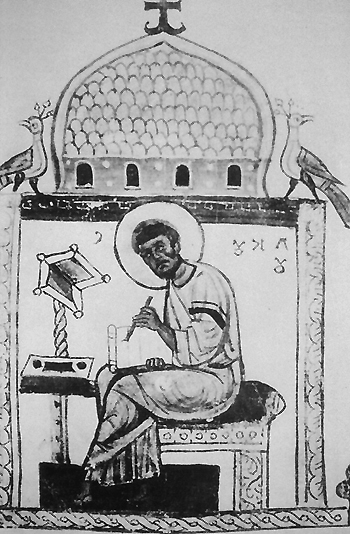

One of the original disputed sources for the dumy epos and early masterpieces of Kyivan-Rus literature is the ancient Kyivan-Rus war chronicle, The Lay of the Warfare Waged by Ihor, Son of Svyatoslav, Grandson of Oleg, or more commonly known as, The Song of Ihor’s Campaign (Slovo O Polky Ihorevi). Written at a time of feudal fracturing, the song tells of one of the historical princes of Kyivan-Rus, Prince Ihor, and his disastrous campaign undertaken in 1185 against the Mongol hordes. In Arsenal Dovzhenko follows the convention of The Song of Ihor’s Campaign, beginning with an epic invocation. Similar to Zvenyhora’s beginning, there is a calling to the muse and a historo-literary antecedent in ironic parody of genre convention. | ||

|

Ivan Padalka's

Illustration to a 1918 Kyiv Republication of The Song of

Ihor's Campaign

|

|||

Zvenyhora’s opening evoked Shevchenko and Semenko. Arsenal’s opening evokes The Song of Ihor’s Campaign and Modest Mussogorsky’s opera Boris Godunov, but both in the modality of ironic parody.[156] The invocation to the muse in The Song of Ihor’s Campaign begins:

Wishing to summon forth song in someone’s honor, Boyan the Wise

Would let his thoughts flow through the tree of his dreams

Would let them speed as the grey wolf over the earth,

Would let them soar as the blue eagle under the clouds.

They say he would recall warfare of old.

Then he would loose ten falcons upon a flock of swans

And when a falcon fell upon a swan,

Then that swan would cry out in song

Of ancient Yaroslav, of the valiant Mystyslav

who slew Rededya before the Kassog host

Or of Roman the Fair, son of Svyatoslav

but my brethren, Boyan

loosed not ten falcons upon a flock of swans

but let inspired fingers fall upon living chords,

and they themselves sang out glory to princes.[157]

| Prosaically figuring the chronicler, the opening passage from Ihor’s campaign hyperbolizes on the oratorial ability of Ihor’s diarist. Instead of having a chronicler write of the last Tsar of the Romanoff dynasty’s deeds, Arsenal figures the final monarch and Tsar of the Romanoff dynasty, Ihor’s hereditary successor, alone and monkish, attempting to write his chronicle: “September 12th. Today I shot a crow. Splendid weather. Nicky.” In contrast to the Song of Ihor's Campaign’s baroque invocation, the Tsar’s impotence and mundane nature is figured in Arsenal as a paucity of creativity. In close-up, the last Tsar is figured as static and immobile. Dovzhenko’s screenplay adaption reads, “Not a single larger conception falls across the tsar’s head. Boring and grey, the last of the tsars.”[158] While largely not referred to in the West, Dovzhenko is not unique in his drawing upon The Song of Ihor’s Campaign, but follows in a line of Ukrainian writers beginning with the earlier national revival[159] to his own time and compatriots’ modern translations of The Campaign[160]. |

|

||

|

Miniature from

Dobylovoho's Evangel (1164)

|

|||

Like the “Mighty Heaps” and particularly Mussogorsky’s opera, Boris Godunov’s re-articulation of Slavic peasant folk melodies to re-invigorate classical forms (eg. opera), there is a connection from Arsenal’s outset between the Tsar and the people’s suffering figured through contrast and pathetic fallacy. In Boris Godunov, because of Tsar Boris’s heinous killing the throne’s true heir (the young Dmitri), the people or masses suffer hunger and ill-fated times. In Arsenal’s conception, through metonymy and visual counterpoint, because of Tsar Nicholas II’s feeble mindedness, the Russian empire’s external landscape takes on a desert-like nature.

|

Unlike the village portrayed in Earth, Arsenal’s village is barren and empty; the mother literally falls in the fields; the streets are populated by immobile women, starving children and cripples Responsibility for the mother and women’s suffering in Arsenal’s opening is shown through inter-cutting. Women stand separated from each other in an abandoned village. | ||

| Arsenal Still, Village Mother with Children | |||

Alone

in a field, another woman sows grain. In close-up, Tsar Nicholas II

writes a letter. By a visual metonymy, the implied suggestion is that

because of the Tsar’s moral abandonment, the woman’s sons are no more.

The Tsar’s traditionally prescribed and defined role as ‘servant of

the people’ has been forsaken. Spiritually, morally and physically

displaced and abandoned, the peasants literally fall in the fields.

Nicholas II’s cloistered St. Petersburg life offers little sympathy.

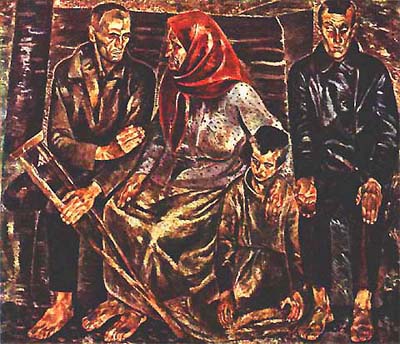

Anatoly Petrytsky, Invalids (1924) National Museum of Kyiv

Dovzhenko portrays the village populated by crippled men. On one level, this comes from historic fact. These are returned, incapacitated veterans, unable to reassume their traditional role of working the fields. In his contemporary theatrical variant, playwright Mykola Kulish satirically portrays this tragic situation in his banned play of the Ukrainian revolution:

In the basement Nastia stands like a statue. In the doorway crawls a legless soldier wearing the ribbon of the St. George Cross.

Ovram: Don’t you recognize your husband, Nastia? Hallo! As you can see, they've shortened me a bit, made me lower than anyone else. But it does not matter. I’ll go back to the comrades in the factory, they’ll lift me up. I’ll crawl back but I’ll get there. For two months I’ve been crawling back to you. Why are you staring? Come and let me put my arms around you, though I’m only half of your husband.

(Sonata Pathetique)[161]

Amputated by land mines, these returned veterans are the First World War’s victims.

|

Dovzhenko shows one of these returned amputated veterans alone and without legs, a shining St. George’s veteran’s cross displayed on his chest. Rather than an overt narrative, the image is iconic. Like much of Arsenal’s aesthetic, the image has affinity with painterly tableau and Marxist secularization of the traditionally religious Eastern Orthodox icon. | ||

|

Arsenal Still (1929),

Returned Amputated Veteran

|

In this opening sequence nother good contemporary art historical

analogue to what Dovzhenko is figuring cinematically is Fedir

Krychevsky’s “Life” tryptych. As previously discussed, Dovzhenko had

worked with Krychevsky’s brother, Vasyl as set-designer for Zvenyhora

(1927). He had studied under both of the brothers at the Kyiv Academy

of Fine Arts.

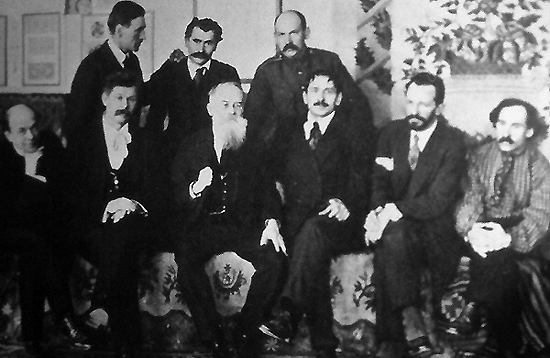

Ukrainian State Academy of the Arts: (standing left to right): H.

narbut, V.H.Krychevsky, M. Boichuk,

sitting: A. Manevich, O. Murashko, F. Krychevsky, The Historian M

Hrushevsky, I Steshenko, M. Burachek

In the following year,Dovzhenko would work with Krychevsky’s son as set designer for the final work of his trilogy, Zemlya (1930). The elder brother, Fedir, was a well-known painter under whom Dovzhenko studied at the Ukrainian State Academy of Arts.

| In 1928 at the Venice biennial, Fedir Krychevsky had been awarded one of the highest awards for his painterly triptych, “Zhyttia” (Life). Done in an expressionist manner and reminiscent of Klimt or Munch’s symbolic expressionism and friezes, the “Zhyttia” triptych was divided into three larger panels, “Love”, “Family” and “Return” (1925-1927). |  |

||

|

Fedir Krychevsky, circa 1929

|

|

In Krychevsky’s “Zhyttia triptych”, the first panel, “Love”, depicts a young peasant couple in an embrace much in the style of Klimt’s, “The Kiss” (1907-1908). In Krychevsky’s variant, the young peasant maiden is in a traditional skirt, kneeling with hands held up and together, the two young villagers form a solid column-like foundation. In Arsenal, one of the larger questions surrounding the hero will be where he should ‘stand’. “Tymish Stoyan” literally translates as “Timothy, the one who stands”. In the film the demobilized soldier and former arsenal worker’s quest will be a search for foundations or bases from which to stand. | ||

| Fedir Krychevsky "Love", First Panel, Life Triptych 1925-1927 |

|||

Krychevsky’s central panel is entitled “Simya”, translated, “Family” but in the Ukrainian homology having etymologic connotations with ‘seed’. A family of husband, wife, child and grandmother are depicted in iconic form and the centrally presented madonna is evocative of Klimt’s “Three Ages of Woman”. The panel underscores woman’s creativity and power. In Arsenal, Dovzhenko figures the tropes of family and women’s nourishing fertility in a displaced and misplaced variant. The women are presented barren, emaciated and against desert-like landscapes.

Fedir Krychevsky, Family "Simya", 2nd Panel in in Life "Zhyttia"

Tryptich (1927-29)

In Krychevsky’s centre triptych a traditionally dressed madonna-like peasant, with an embroidered Ukrainian ritual cloth, ‘rushnyk’, forms a connecting link to bind three generations of rural family around her. The panel combines a closely knit pictorial expressionism with an Byzantine iconic reverence for the family. Perhaps the central poetic conceit Dovzhenko in Arsenal regards the purpose to which the Ukrainian population should be put. In Arsenal this cloth is depicted in the opening scene’s ‘khata’ (cottage) background. It lies on the ground, torn and tattered.

| Krychevsky’s triptych’s final panel is called “Return” . It depicts an older ghostly pale aged peasant father, mother and their returned uniformed, World War I amputated son. The peasants are barefoot in the traditional white ‘chumak’ peasant attire, and while the son has returned in boots, he is missing a leg. The father’s hands congregate in front of his loins and a look of desolation deforms his face. The mother tearfully leans on her returned soldier son who now carries a cane and is depicted in an ugly military green. In contrast to the blush of Krychevsky’s “Love” and unity of “Family”, the deathly white of the face and symbols of impotence in “Return” are jarring. In Arsenal amputated soldiers populate the film. |

|

||

|

Fedir Krychevsky, Return,

(1927-1929)

Final Panel of Life (Zhyttia) Triptych |

The extended metaphor of amputation is a gruesome politico-cultural trope. Witness Kulish’s theatrical variant from Sonata Pathetique:

Sailor: Are these your legs, mate?

Ovram: Mine are in the ground. Imperialism has buried them.

Sailor: And these are half-buried by the bourgeoisie.

Ovram: Yes.

Sailor: So there isn’t much difference between them.

Ovram: (crawls to the legs and inspects one boot): Only one size different. (His head droops)

Sailor: Down with the bourgeoisie![163]

The metaphor is also economic and commenting on Marx’s notion of base and superstructure, but also Ukraine’s foundation or, rather, lack thereof.

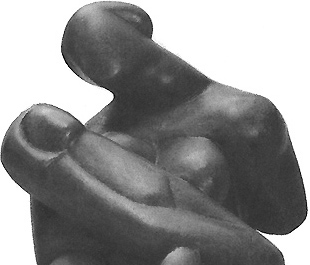

In Arsenal’s painterly aesthetic there is a complex Marxist transfer and secularization of the Eastern Orthodox Byzantine icon. In gesture and inter-title, Dovzhenko compositionally sets up iconic parodies of Slavic and Byzantine iconography (‘The Three Saints’, Boris and Hlib, 13th C.)[164]. Overtly, Arsenal’s various sequences rearticulate Eastern Orthodox Byzantine icons for contemporary times. The Eastern Slavic religious icons of the Virgin Hodegetria (She Who Knows the Way, 16th Century) and Virgin of Vladimir (early 12th Century) are figured in ‘internationalized’ tableau-like scenes of various countries’ soldiers returning home to child-carrying warbrides[165] . In these iconic images, Dovzhenko presents a unique modernist syncreticism.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Detail from Slavic Icon

"Virgin of Vladimir", 12th C.

|

Mother and Child,

Alexander Archipenko, 1913

|

Still Image, Arsenal's

Unmarried Warbride Madonnas

|

Later, Dovzhenko displaces and transfers various traditionally religious iconic motifs onto Ukraine’s national poet, Taras Shevchenko, parodying a strange nationalist fetish and Easter parade veneration.

|

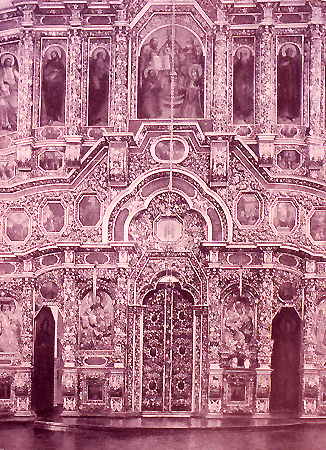

One may see Arsenal’s aesthetic as an Ikonostasis for contemporary revolutionary times. A focus for both instruction and veneration found in Orthodox churches, the ikonostasis consisted of a multitiered screen or icon panel[166]. The iconic element thrusts towards a visual connection with Ukraine’s largely oral based rural masses. In a later novelette only able to be published during the Khrushchev thaw, Dovzhenko would subversively write about these iconic visualizations officially proscribed by Soviet culture. | |||

|

Slavic Ikonostasis

Detail, Lviv

|

||||

Utilizing a memoirist’s voice of a child’s naivité to get past Soviet censorship against ‘religious’ motif, Dovzhenko describes the white walls of the village ‘khata’, or cottage, in which he grew up:

And on the white walls under (the Gods), all the way to mother’s dishes there hung a lot of beautiful pictures - the Pochayev Monastery, the Kievan Monastery, the Simono-Kananitsky monastery at Novy-Afon near the city of Sukhumi on the Caucasian coast. Over the monasteries holding herself in the breeze was the Virgin Mary (with Ukrainian embroidered cloths, rushnyky) where angels, winged like baby goslings, flew round her. (There were pictures of more worldly matters, too - the life of Man, St. George the Victorious, Cossack Mamai.) But the picture, (the one that meant much more than all the monasteries, tsars and princes put together) was the picture of (God’s terrifying last judgement), which Mother had bought in exchange for a hen at the market and brought home to terrify her enemies - Great-grandma, Granddad and Dad. It was so dreadful and (together with this instructive) that even Pirate, our dog, was afraid to look at it. The upper part of the picture was filled with Granddad and all the saints. In the middle the dead came crawling out of their graves, some to Heaven - upwards and others down. Through all the pictures middle and lower parts a great azure snake twisted and turned. (He was alot thicker than those snakes that we used to kill in pumpkins.) And beneath the snake, below everything was burning, like an inferno. That was Hell. . .Many were the sins, and many were the punishments, but for some reason none of us feared them any more. At first I had been terrified by this picture, but gradually I became accustomed to it, as a soldier at war becomes accustomed to the thunder of guns.[167]

| Forgrounding traditional iconic motifs, Arsenal is Dovzhenko’s neo-Byzantine Ikonistas or modernist Inferno.[168] Presenting a contemporary iconic apocalypse or ‘Last Judgement’, there are parallels . Unlike the relatively new art of the cinema and its then not as well-established codes and grammar, the Byzantine icon, ikonostasis and accompanying visual grammar would be an easy and natural analogue for the theocentric village masses. As an early commentary about the Byzantine icon would state, “In a picture even the unlearned may see what example they should follow. In a picture they who know no letters may yet read.”[169] |

|

|||

|

Last Judgement "Stranshiy

Sud" 15-16th Century, From the Church of the Virgin, Mshani

Ukraine

|

||||

Referenced in Zvenyhora, one of the great Slavic iconostasis of which Dovzhenko would later speak about was accomplished by Andrei Rublev in Zvenyhorod.[170] In Arsenal’s opening sequence’s village street and doubled later in the countryside, three peasant women stand at forty-five degree angles. From an action, plot and even protagonist’s point of view, no ‘event’ occurs. From a conventional three act narrative perspective, the sequence could be cut without disturbing a linear development of plot. Like many of the scenes in Dovzhenko’s trilogy, the tableau is not predicated on movement, ‘action’, plot point or an event to move the narrative along but works through emblem, symbol, iconic typology and static painterly composition.

|

Visually, the tableau is reminiscent of Andrei Rublev’s “Old Testament Trinity (1422-27)”.[171] In Rublev’s icon, the Trinity’s mystery is presented as three female angels positioned around a table in amiable conversation. Integrative parts of God’s nature are anthropomorphized to present a model for community. Depicted through the angels’ flowing robes, meeting gazes and free and easy communion, the figures present an icon of the togetherness, ‘sobornist’, of God and man. Dovzhenko’s trinity is presented through three figures’ hidden, kerchiefed and coated bodies. Fenceposts divide and each figure refuses to meet the other’s or viewer’s gaze.

|

||||

| In Rublev’s icon, the uncovered smiling right angel turns both to viewer and left angel. The left angel naturally turns to audience and central angel. The central angel lets her hands fall to the icon’s focal point, a communion chalice through which the audience is invited to complete the table and union. The painting engenders a thirst for God. In Dovzhenko’s inversion, each peasant woman’s gaze is directed away from the viewer. The viewer’s gaze is led through a mutual turning away to the frame’s overwhelming white, parched, grainy centre. In Rublev’s icon the three harmoniously interrelated female angels present a compositional model. The incomplete table invites the viewer’s perspective and interpellates a ‘fourth’ for its completion. Through the Byzantine icon’s inverse perspective, Rublev’s icon thrusts its focus out to the viewer inviting the audience in but reminding man of his distance from God. Dovzhenko inverts this, thrusting the viewer’s gaze frame centre, inviting them to contemplate their own isolation and alienation from other audience members. Statically inviting reflection, Dovzhenko allows the sequence to linger.[172] |

|

|||

|

"Old Testament Trinity",

Andrei Rublev 1422-27, Tretyakov Gallery

|

||||

Building his larger mythopoetic as a sequenced slide-show ikonostasis, Dovzhenko begins in historic fact and classic art historic typology. Out of this, he constructs an expressionistic, symbolic, Neo-Byzantine and secularized typologic form of conceptualization. There is a gesture similar to both the Western European modernists’ primitivism and rearticulation of ‘other’ cultures (eg. Brancusi, Gauguin, Modigliani, Archipenko, Boichuk) but also an appropriation of the current historic event and zeitgeist, articulated in the codes of the art historical antecedent and Byzantine iconography.

|

In contrast to a traditional three-act narrative with roots in realist drama, Arsenal is visually closer to that of modernist pictorial fine art or neo-Byzantine set of composite iconic tableau. Through this type of multi-paneled Eastern Orthodox ikonostasis, ‘theatrical’ narrative structures are rearticulated to a more closely fit revolutionary concern. Like Picasso with “Guernica”(1937), Dovzhenko takes the events of the Ukrainian Revolution and Civil War, presenting them through a modernist refraction that presents a mythopoetic and ikonostatic tableau played on through a complex kinetic layering of meaning. The reference to modernism’s pictoral representation is not only on the level of elective affinities or subject matter but in composition and aesthetic antecedent. Arsenal is not so much a ‘historic war movie’ to be read as theatrical narrative as it is a modernist ‘dadaist’ gesture to shock the viewer out of conventional viewing modalities. Composition, stasis and cognitive function take precedence over narrative arc. | ||

|

Slavic Byzantine

Ikonostas with various iconic narratives

|

| One of the better-known sequences in Arsenal is the agonizing portrayal of the laughing gassed soldier in the opening scene. The historical critique reads this sequence as emblematic of Dovzhenko’s ironic commentary on war’s insanity[173] and its ambivalent connections with the rest of the film’s ostensible purposes as revolutionary commemoration.[174] |

|

||

|

Ambrose Buchma as Gassed

Soldier, Arsenal

|

Amid various barbed wire fronts, groups of mask-wearing soldiers march in confused attack formations. Through similar uniforms and a foregrounded lack of differentiation, it is difficult to distinguish competing armies.[175]

Undifferentiated Soldiers, Arsenal

Emphasized through the sequence by cinematographer, Danylo Demutsky, a silhouette-like high-contrast conveys an anonymity of soldiers denying their role as representatives of different armies. The sequence’s varying shades delineate silhouetted fighting figures, not members of good or bad forces, but largely undifferentiated figures.

The war’s insanity and senselessness is conveyed in a brief series of six shots surrounding a single soldier’s changing expressions. Moving variously to the left and to the right amid clouds of smoke, a single German soldier[176] rips off his gas mask revealing an unshaven, dirty face. Tired, worn and surrounded by changing winds, the soldier goes through a spectrum of expression. An inter-title reads, “There are gases that make a person’s soul gay”. Gazing at a fallen comrade, the soldier convulses in laughter. A fellow soldier’s head and hand stick bulbous and vegetal out of the earth[177].

Although the soldier, played by Ambrose Buchma, is only on the screen a half minute, it is this cameo which is expanded into a poster by VUFKU to promote the film. Later, this sequence is somewhat ironically and misguidedly cited as Buchma’s greatest role. Buchma would have been known to contemporary Ukrainian audiences. The leading actor within Kyiv’s Les Kurbas Berezil Theatre, he had played a series of roles in the VUFKU silents: Vendetta (Kurbas, 1924), Macdonald (Kurbas, 1924) Jimmy Higgins (Kurbas, 1928), Taras Shevchenko (Chardynyn, 1926), Taras Triasylo (Chardynyn, 1927) and Mykola Dzheria (Tereschenko, 1927). In February of 1927, KINO had devoted a larger article to Buchma calling him the most known ‘physiognomy’ on Ukraine’s unknown screens.[178] Recently starring in Chardynyn’s Shevchenko and Taras Triasylo, Buchma had in two different features graced the screen as Taras Shevchenko. In Tereshenko’s Mykola Dzheria, he had also starred as the haidamak leader, Mykola Dzheria .

|

|

||

|

Ambrose Buchma as Taras

Shevchenko (1927)

|

Ambrose Buchma as Gassed

Soldier (1929)

|

In this cameo, Dovzhenko casts Buchma in a role that would be termed ‘against type’. For the contemporary Ukrainian audience, the gesture would raise questions in light of Buchma’s previous roles as Ukrainian heroes, Dzheria and Shevchenko. This brief opening appearance, insanity and death would herald a contradiction to spectatorial expectation. In Arsenal’s opening minutes, the film would raise questions about the nature or type of ‘ten year commemoration of the revolution’ that Dovzhenko was supposedly celebrating.

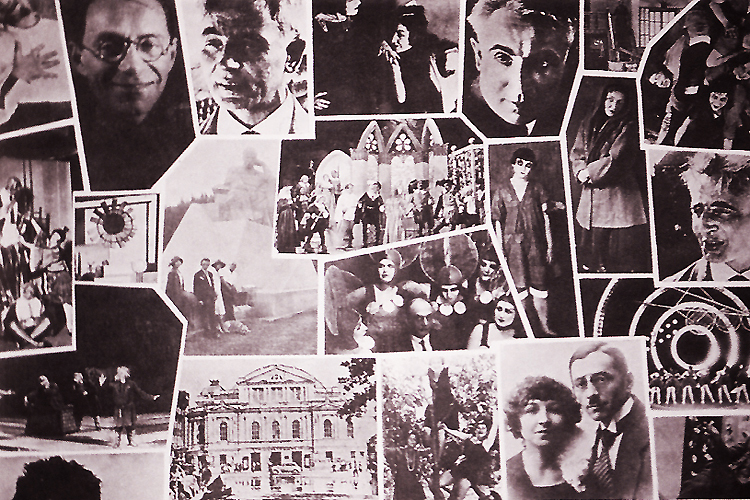

For the Power of the Soviets, Victor Palmov, 1927

Building on transformative gesture, Buchma’s expressionist acting method was emblematic of the Les Kurbas’ Actors Studio and Berezil Theatre[179]. For the most part, Dovzhenko’s acting ensemble and film crew for his silent trilogy was derived not from the schools of Meyerhold, Vakhtangov Stanislavsky, Tairov and Moscow Art Theatre, but from the suppressed Kyiv Lysenko Music and Drama Institute and the Berezil Theatre studios[180]. Les Kurbas was considered Ukraine’s most important twentieth century theatre director/theoretician. In style, aesthetics and repertoire, Kurbas had elevated the Ukrainian theatre from a largely provincial non-entity, working in farce and comic operetta, to a higher level of experimentation and dramatic creativity. With over 300 actors, six actors’ studios, Berezil was the focal point for theatre in Ukraine and a natural point of connection for the nascent and recently moved Kyiv VUFKU studios. Kurbas had developed a rigorous actors’ school and system for intellectual and technical training while also teaching at Kyiv’s Lysenko Music and Drama Institute. Dovzhenko and many of the destroyed or suppressed productions from VUFKU in this period would draw on the acting and creative talent developed out of Kurbas’s Berezil workshops and actors’, directors’, playwrights’ and set designers’ laboratories and theatre (1922-33).

Les Kurbas Theatre Montage: Many of Dovzhenko's Silent Trilogy Actors,

Set Designers and Productions Workers would come from Berezil

In the year of Arsenal’s production, Berezil had staged what became one of the controversies of twentieth century Ukrainian theatre, the subsequently banned Narodnyi Malakhii (National Malakhii, 1928). Part of a ‘national quartet’ by Berezil’s house playwright, Mykola Kulish[181], the play and the larger tetralogy of which it formed a part would come to be considered one of the few masterpieces of twentieth century Ukrainian theatre. Along with Kulish’s next proscribed piece, Sonata Pathetique (1930), dealing specifically with Ukraine in revolution, these works resonate with Arsenal in theme and subject matter. The connections among Berezil, Kurbas, Kulish’s tetralogy and Dovzhenko’s silent trilogy run from the same stable of actors[182] and group of designers[183] to the association of Dovzhenko, Kulish and Kurbas’s in VAPLITE to unexamined thematic relationships. In an early review of Narodnyi Malakhii that he would write for Vechirniia Kyiv, Dovzhenko’s interest in Kurbas and Berezil is clear.[184]

Most of Dovzhenko’s trained actors for the silent trilogy would come out of the modernistic theatrical ideas of Kurbas’s Molodyi and Berezil Theatre[185] For Arsenal, Dovzhenko would make extensive use of two of Berezil’s set designers, Iosef Schnipel and Vadym Meller.

|

|

||

| Vadym Meller, Cubofuturist Composition, 1918 |

Vadym

Meller, Costume for Prokofiev's City (1924)

|

Prior

to working with Dovzhenko, Meller had collaborated with the

constructivist, Oleksandra Ekster, in staging Prokofiev’s City

and acted as one of the founding members and artistic directors of

Kyiv’s Berezil Theatre.[186]

Because Kurbas, Kulish and Berezil were subsequently liquidated and

banned, connections between Dovzhenko and this grouping became muted.

Pronouncing connections between Berezil and Dovzhenko was less than

desirable in Soviet publication[187]

and lost on western film historians who would follow the lead of

Soviet Moscow Art theatre prescription[188].

Boardings and Departures: The Train of Revolution

The revolutionary committee is not a bedroom. It isn’t even a railway station where you can doze. It’s a locomotive.

(Mykola Kulish, Sonata Pathetique)[189]

Le Théâtre, c’est l’âge du cheval. Le Cinéma, c’est l’âge de la machine.

(Fernand Leger)[190]

Intercutting the out-of-control forward-moving train with a single soldier playing an accordion, Arsenal’s train sequence has been called a lesson in montage and film technique. Foregrounding kinetic plastic form through geometric abstraction, Arsenal’s train is reduced to a series of lines in motion. Bohdan Nebesio comments,

The prevalence of diagonal line in Arsenal is particularly striking. This effect was achieved by simply altering camera placement, thereby turning horizontal lines into diagonals within the frame. Most shots before the train crash form diagonals, as do those of staircases, bridges and buildings. In one instance the horizontal plane of a bridge moves to form a semi-diagonal.[191]

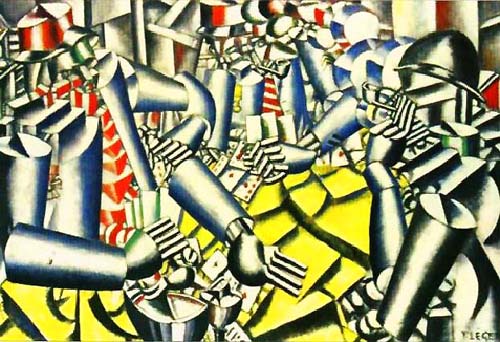

In Arsenal, the movie screen is appropriated as a painter’s canvas or framed rectangular surface onto which is composed a kinetic organization of foregrounded plastic geometric form. Constantly set up in Arsenal is a dialectic between the screen as illusionistic space and planar surface. There are parallels with Eisenstein’s aesthetic, debts to cubist paintings such as Leger’s geometric reduction of soldiers’ bodies in “La Partie des Cartes”(1917) and the early French avant-garde film, particularly Gance’s, La Roue (1922). In Arsenal, Dovzhenko isolates limbs and geometrically foregrounds sleeping soldiers’ heads as volumetric spheres.

Fernand Leger, La Partie des Cartes (1918)

Continuing the intra-psychic and social division discussed in Zvenyhora, Arsenal’s hero, Tymish, is introduced through a complex doubling and split. A crowd of soldiers pushes and shoves as they try to board the train. Two soldiers fall into argument. Inter-titles read: “Come on - pull off our Ukrainian boots. Take our Ukrainian coats, too. You’ve been torturing us for three hundred years”. This reference is to Bohdan Khmel’nytskyi, historic leader of the cossack state. Explicitly, the ‘three hundred years’ refers to Khmelnytskyi’s 1654 treaty of Pereiaslav with Muscovy’s tsardom. Resulting in Ukraine’s subsequent ruin, the treaty is regarded as the turning point in Ukraine’s transformation into a province of the Russian empire (i.e. Malorossia, Little Russia). Dovzhenko designates 1654 and Pereyeslav as the date marking Ukraine’s descent into colonial domination following Shevchenko.

In Arsenal a group of demobilized World War I soldiers spit seeds and watch the Easter/Independence Day parade perched on a large equestrian statue of Khmelnytsky. Erected in the centre of Kyiv by Tsar Alexander the III (1881-1894), the statue has Khmelnytskyi’s outstretched arm pointed northward as indication of Ukraine’s supposed desire to be historically linked with Russia. Dovzhenko plays on the statue’s ambivalent directionality and historical connection.

Prefacing the presentation of the film’s hero, Dovzhenko has both Russian and Ukrainian demobilized soldiers doubled by the same figure, a chubby cherubic boy[192]. At this point in Arsenal, the main hero, Tymish, has not yet been presented. When he is introduced shortly after this doubling, it will be in a curious second doubling pitting a confrontation between the returned demobilized soldiers and a band of nationalists. Tymish will be in opposition to a young man and leader of a group of soldiers from the army of Ukrainian National Republic.

When the two young soldiers argue, visually there is no difference between them. In the Ukrainian original of Arsenal, the young Russian soldier lapses into Russian in the inter-titles. Lost or submerged through Russian inter-title versions, this creates a strata of meaning lost to the West.[193] Flattened out of what Jay Leyda bizarrely termed, “Shelley Hamilton’s sensitive American adaptation”[194], the English-titled version of Arsenal aligns itself with a Russian linguistic dominant which does little justice to Dovzhenko’s semantically-loaded shift between languages. In Arsenal, after one of the soldiers lapses into Russian ‘eto ya?’, the diegesis immediately breaks, cutting to the previously buried head and hand of a fallen World War I soldier. Metonomyically, the association encourages connections between language and World War I’s carnage against a backdrop of the Russian imperium. In erasing this strata within Arsenal (the versions of Arsenal and Earth that we have in the West are ‘Russian’ inter-titled and edited), western critics would agree that ‘Arsenal simply presents a ‘dialect’ of the Russian Revolution’. Dovzhenko’s original language/power differential subtly presents a different picture.

| To make more clear as to how this necessarily submerged and semantically-loaded linguistic shift operates, it is wise to glance at one of Dovzhenko’s novelettes. In Zacharovana Desna Dovzhenko similarly presents this language politics through a schoolboy’s encounter with education’s imperializing function. Similarly lapsing into Russian[195] at key points to convey another layer of meaning, Dovzhenko writes an allegory of a child’srealization that he is a Ukrainian peasant’s son after his encounter with the Russian imperium and schools and, ironically, a teacher. |  |

||

|

Dovzhenko's self-portrait

as schoolboy, note the embroidered shirt

|

One of the larger questions Arsenal poses itself is the role of national consciousness in the Ukrainian revolution and civil war. Continuing the character doubling discussed above, Arsenal’s main hero, Tymish, the demobilized soldier and Arsenal worker, is born and makes his first appearance in the film out of the confrontation between himself and a UNR officer. In a sequence of inter-cutting between Tymish and the UNR Officer, the latter runs toward the railway tracks pulling out his sabre and gun shouting:

In the name of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, you are ordered to surrender your arms.

Tymish: In the name of the Ukrainian People? Who said so?

Arsenal poses the politically motivated question, “Who has the right to speak ‘in the name of the Ukrainian people’?”

|

If there can be said to be any movement or progression within his character, Tymish’s development in Arsenal will be a development of a social identity. Dovzhenko figures this development as specifically a former demobilized World War I soldier’s identity. After the train wreck, Tymish returns to his former arsenal factory. The factory owner questions him about his identity:

“Who are you?” “A demobilized soldier and arsenal worker - I have the honour of returning. “A Ukrainian? ? . . .A deserter?” |

|

||

|

Tymish, Arsenal's

demobilized Soldier

|

At this moment of historical fissure, there is a question and ambiguity as to larger societal identities. That of a ‘worker’ and a nationally defined identity are both in natal stages: unfixed, historically free-floating and up for ‘social’ and ‘intra-psychic’ contest. Free from imperial domination, Ukraine has not yet become a ‘worker’s state’. It is also not yet firmly in the Bolshevik’s hands. A politically defined ‘national’ consciousness is in its birthing stages. This close feeling of a ‘newborn social identity’ is figured in Arsenal through the soldiers returning home to their wives to find a new ‘child’ born. The different soldiers all repeatedly ask ‘Who?’. Immediately after, in a parallel scene the arsenal manager asks Tymish ‘who’ he is. Typologically, Dovzhenko figures Tymish as the still not fully ‘identified’ illegitimate child of revolution.

Regarding the context of this sense of territorialized but still natal national consciousness, it is again illuminating to look at Dovzhenko’s later novel, Zacharovana Desna. Here, this nascent sense of national awareness is similarly figured in a little boy’s questions to his father. Dovzhenko writes:

Something twinkled far away on the river. I looked again - yes, a light. Rafts were coming down. I could hear people’s voices. I turned round to Dad again.

“Dad?”

“What it is, son?”

“What’s that floating along the river?”

“That’s folks from a long, long way off. From Orel way. Russian people coming from Russia.”

“But what are we? Dad, aren’t we Russian?”

“No, we’re not Russian.”

“What are we, then? Dad, what are we?”

“God knows what we are,” said Dad rather sadly, after a moment’s thought. “We’re just common folks, son. . .(Kakhli) We’re the ones that bake the bread. Muzhiks, you could call us. Yes. Just muzhiks, that’s all. Once, they say, we were Cossacks but now there’s only the name left.”[197]

Dovzhenko and his father, early 40's.

Neo-Colonial Paralysis

While the Ukrainian nationalists under Petlyura were masters, the Ukrainian language was irrationally forced on the heterogenous Russian population.

(Jay Leyda, Kino)[205]

She: Have the glorious Cossack banners of Bohdan, Doroshenko, Kalnysh and Honta utterly faded for you?

(Mykola Kulish, Sonata Pathetique, Kyiv, 1930)[206]

Before the outbreak of civil war, Dovzhenko presents Ukraine in a state of paralysis. Factory mechanisms and gears stop, workers stand silent, men aim guns, the urban bourgeoisie sit immobile at dinner tables. In a delicate intercutting, heads and cranks are wound to breaking points. Building tension towards Arsenal’s final violent climactic sequence, Dovzhenko fragments the narrative into a series of increasingly static tableaux of Kyiv’s populace in paralysis.

| Zvenyhora referred to Leger’s surrealist inspired Entr’acte; Arsenal dialogues with Rene Clair’s science fiction slanted, surrealist inspired, Paris Qui Dort (1924). Presenting a surrealist-like vision of an empty metropolis in Paris Qui Dort (Paris Who Sleeps), French avant-garde filmmaker, Rene Clair, stills the streets of Paris through a mad scientist’s ‘motion’ machine. |

|

||

|

Paris Qui Dort (1924)

|

In Arsenal, Dovzhenko arrests several symbolic segments of the Kyivan populace in various poses of immobility. Soldiers smoke cigarettes. Groups of urban luggage-carrying bourgeoisie stand immobile in the streets. Investing Kyiv’s streets with a profound emptiness, the cinematographer, Danylo Demutsky compositionally frames the urban still life of this sequence reminiscent of Clair’s antecedent, the surrealist-admired French still photographer, Eugene Atget.[207] Admittedly, the static images of various immobile segments of the populace and empty city streets build tension, but also thematically follow on the larger political indecision and neo-colonial position that Ukraine finds itself on the eve of 1917.

Dovzhenko presents the urban, Russified metropolis, Kyiv, as internally divided. At a point where national aspirations manifest themselves, the city’s topography succumbs to a state of physical, metaphorical and visual paralysis or internal division. This inner division or conflict in Arsenal is presented through Dovzhenko’s doubling of figures. Subsequently, the resulting urban paralysis is literalized in shots of a paralytic soldier agonizingly making his way across a deserted Kyiv street. This stasis or trope of paralysis is within Arsenal from the beginning. The peasant women are presented immobile, alone or later by gravesites. Soldiers refuse to follow orders, frozen as statues. In the countryside peasant women stand paralytically. In Kyiv, mothers are arrested in frozen motion while they are watching their children sleep.

|

The final much commented sequence in Arsenal presents Tymish besieged and out of machine gun bullets. Confronted by a Petliurite band and fired at, Tymish exposes his chest and repels the barrage. Western critique and Soviet commentators read this conclusion as emblematic of Bolshevik revolutionary triumph[209]. This contextualization wishes to add another valence. | ||

|

Tymish Baring His Chest in

Arsenal's Famous Final Scene

|

The passage begins with Tymish having trouble with his machine gun. Three soldiers with rifles run towards him. Tymish gets up to fix the gun. An exchange between battling groups occurs. The variant of this scene in the 1964 publication reads:

At the arsenal’s last bastion Tymish is riddling the enemy with his machine gun. Hayadmaks run toward him. Fire! Fire! No good. Tymish’s machine gun is jammed. He kicks it in rage, then straightens up and begins to hurl rocks at the advancing enemy.

“Stop!” shout the dumbfounded haydamaks.

“Who’s with the machine gun?”

“A Ukrainian worker! Shoot!” Tymish throws his shoulders back, rips open the shirt on his chest, and stands as if made of steel. His eyes blaze with a terrible hatred and anger.

Three volleys do the haydamakas send at him until they see the uselessness of their shots and shout in stupefaction, “Fall! Fall!”

And then they themselves disappear.

Tymish stands - the Ukrainian worker.[210]

Commentary of this sequence reads Tymish refusing to die as the triumph of Bolshevism and essentially follows the above published scenario[211]. In contrast, early denunciations of Arsenal question Dovzhenko’s conclusion for its ‘pessimism’[212]. Instead of ending with the revolutionary triumph and the historical entrance of Bolsheviks into Kyiv, Dovzhenko ends Arsenal with an iconic image that necessitates a reading that must allude to later events to present ‘the triumph of Bolshevism’. In Arsenal’s final scene Tymish is not marked in either the published scenario or the film print as the unkillable ‘Bolshevik’ or ‘Bolshevik worker’. Tymish does explicitly announce himself as a ‘Ukrainian Worker’[213].

Both the ‘published scenario’[214] and commentary on Arsenal identify the soldiers attacking Tymish as nationalists from Petliura’s UNR ‘Haidamak Kish’. Of the three soldiers attacking Tymish, one is clearly dressed as the previously coded ‘Petliurite’ from the ‘Haidamak Kish’ of the nationalists. He wears a cossacks’ sheepskin cap, has a prominent cossack mustache and carries munitions of the earlier presented ‘haidamaky’. More ambiguous are the figures making up his right and left flank. Excised in mention from published scenario versions, a differently presented figure stands to the ‘haidamak’s’ left. From the viewpoint of costume, visage or dialogue, this figure is given Arsenal’s final inter-title lines. This unnamed figure, who consequently becomes central in Arsenal’s final close-ups, wears a sailor cap and costume resembling not the previously numerously presented ‘haidamak cossacks,’ or Petliurites, but stands incongruously close to the sailor costumes from the Black Sea Fleet of Battleship Potempkin. Iconically, this garbed figure seems out of the Potemkin propoganda or Rodchenko and Lavinskii posters for Bronenosets Potemkin.[215] From his previous film poster illustrator days at VUFKU, these images would be known to Dovzhenko.[216] Already used in Arsenal at the soldiers’ congress highlighting Battleship Potemkin’s gun boat canons, the poster-like Potemkin icon has been referenced before.

Sailor from Soviet Potemkin Propaganda Poster. Compare Arsenal's Final

Figures

The Poster Reads "1905: Glory to the National Heroes on Potemkin"

Tymish is figured against two extremes of the dialectic developed in Arsenal: the Ukrainian nationalists, presented by Petliura’s ‘Haidamak Kosh’, and a symbolic figure presented reflexively by the sailors costume almost out of Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. Both forces turn their guns on Tymish. All three figures have been set up to allude to a mythologization of a certain ideologic standpoint through costume.[217] Earlier in Arsenal competing armies’ soldiers uniforms had been blurred and undifferentiated to figure the insanity of brother-against-brother in World and Civil War; Here the symbolic differentiation of ‘haidamaky’, sailors and Tymish are marked.

Structured as absence in the published scenario, the final shift in action focuses onto Arsenal’s sailor and his curious inter-title speech. The camera moves from the ‘haidamak’. In the film’s final moments, the sailor is now central. Inter-titles read, “Fall, Fall, what are you wearing - armour or something?”[218]. The reference is to Tymish’s body becoming the ‘armoured vehicle’ of revolution and reflexively, a further allusion to Eisenstein’s Bronenosets (i.e. battleship, ironclad) Potemkin[219]. Rather than emblematic for the Russian ‘Bolsheviks’, Tymish, the iron-like unkillable ‘Ukrainian Worker’, stands in a synthetic position between two dialectic poles.

Arsenal ends not with a reconciliation but with ‘Tymish Stoyan’ standing his ground in a historically untenable position. The final close-ups are not of a denouement but agonizing images of Tymish’s scream.

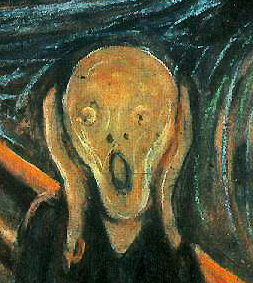

Tymish Close-up for Arsenal's Agonizing Final Silent Scream

Ivan Koshelivets compositionally relates this final image to Edward Munch’s contemporary modernist painting, “The Scream”(1893)[220]. Taking up Koshelivets’ suggestion and putting it into play with earlier discussion of Dovzhenko’s aesthetic in terms of the iconic tableau of the Byzantine Orthodox ‘ikonostas’ and ‘duma’ lament, this final panel may be seen not so much as tidying up loose ends but as the final panel in Dovzhenko’s larger kinetic ikonostatic tableau of the Ukrainian Revolution’s complexity.

|

Similar to Edward Munch’s secularized expressionist play with narrative type tableaux, Arsenal’s final panel iconographically portrays the untenable position of revolutionary Ukraine. Arsenal’s final sequence articulates in a modernist variant, the project’s thematic ambitions not as ‘three act denouement’ but the final panel in a kinetic spatio-temporal ‘ikonostas’ of Ukraine in revolution. The visual paradox is in the silent film’s final scream that cannot be heard. The gesture is profound in the light of Dovzhenko’s earlier dialogue with the ‘duma’ genre lamentory funereal wail and traditionally blind kobzars. | ||

| The Blind Kobzar, V. Haschenko, 1904 | |||