Philosophy, Iconology, Collectivization: Earth (1930)

Introduction |Zvenyhora (1928) | Arsenal (1929) | Earth (1930) | Conclusions

Filmography | Earth Chronology | Bibliographies | Contact

|

If it’s necessary to choose between truth and beauty, I’ll choose beauty. In it there’s a larger, deeper existence than naked truth. Existence is only that which is beautiful. (Alexander Dovzhenko)[221] |

||

Mykola Pymonenko, Reaper 1889, Ukraine |

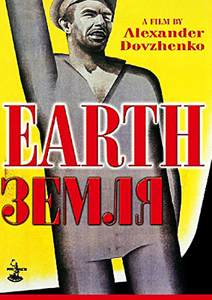

Of the silent trilogy, Earth (1930) is Dovzhenko’s most accessible film but, perhaps for these same reasons, most misunderstood. In 1958 a Brussels’ film jury would vote Earth as one of the great films of all time. Earth marks a threshold in Dovzhenko’s career emblematic of a turning point in the Ukrainian cultural and political avant-garde - the end of one period and transition to another.

Zemlya (Earth), Full Movie, 70 minutes

Zvenyhora spanned millennia in Ukraine’s history. Arsenal looked back ten years to the civil war. Earth draws from the present historical moment (1929) and central topic of the day, collectivization. Dealing not so much with collectivization as appropriating the topic, the film orchestrates philosophic meditation.

| Before its release, Earth was greeted with a cacophony of opposing opinion. Produced in 1929, released in 1930, Earth precipitated a debate that is still not understood. This led to censorship and the film’s reediting of which we have yet to see full restoration. The avant-garde and intelligentsia would celebrate Earth. In a series of party-backed protests the Bolsheviks and Moscow workers’ clubs would rise against it. The debates would also herald the Ukrainian cultural renaissance’s wane and lead to Dovzhenko’s longer self-censorship. A new period would begin in Ukraine marked by purges, terror and a party-orchestrated famine. |  |

||

English Poster for Zemlya, Earth (1930)

|

|||

Appropriating a simpler narrative plan than his previous films and closer to poetry than prose, Earth presents what has been termed a slight narrative structure to reflect on philosophical concern. The following Earth summary proposes congruence in division with the trilogy’s previous two films:

Episode 1: Encircled by family in the Ukrainian steppe, Grandfather Semen spends his final moments of life joking with his old friend. Semen eats a pear near a swaddling newborn before peacefully lying back onto the earth and passing away surrounded by the orchard’s falling apples.

Episode 2: Local kulaks, Arkhyp Bilokin and his family, lament while resisting efforts to collectivize. One of the family members threatens to kill his own horse rather than give animals up for collectivization. Women wail while Arkhip Bilokin reads the paper. What are they printing about the kulaks[223]?

Episode 3: Semen’s grandson, Vasyl, and the local komsomol organize a meeting back in their house to discuss collectivization. While Vasyl and his friends support collectivization, Vasyl’s father, Opanas, is sceptical and reticent about the new ways.

Episode 4: Vasyl brings the village its first tractor leading a delegation through the fields. Overheating the radiator, Vasyl stalls the tractor. The men must devise a way to get the tractor started.

| Episode 5: The peasants plow, till and harvest grain with the help of Vasyl who is driving the tractor. Women tie sheaves and men pitch hay. From planting seed to baking bread, this sequence presents a montage of the production process on the collective. |  |

|||

Earth Still, Wheatfield |

||||

Episode 6: After a hard day’s work, young farm workers meet with their sweethearts. In a strange night mist, Vasyl’s girlfriend, Natalka, takes comfort in his protection. Vasyl dances a hopak on his way home under the harvest moon. He is murdered at the crossroads.

Episode 7: Vasyl’s father leads a funeral procession deciding to support the collective,. Forsaking religious ceremony the villagers bury Vasyl singing ‘new songs’. In a complex montage, this variously censored sequence is inter-cut with: Vasyl’s mother bearing a child; Khoma Bilokin going insane; Vasyl’s girlfriend lamenting her lost lover; the village priest questioning the secular funeral. The film ends with a presentation of the earth’s fertility.

|

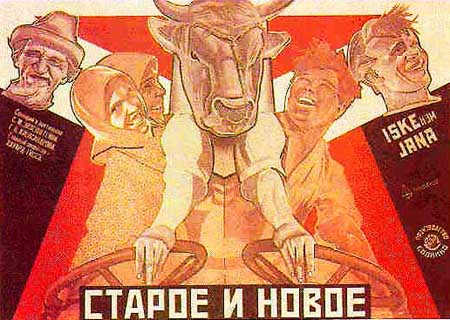

Earth’s aesthetic relies not on formalist gymnastics, camera movement or montage unlike it's closest analogue with regard to collectivization, Eisenstein’s The Old and the New (1929),. Grounded in stasis, the film is predicated on inter-frame composition and a painterly schema. Earth’s formal qualities have kinship with Dreyer’s Joan of Arc (1928) and narrative antecedent in Griffith’s A Corner in Wheat (1909). Unlike Zvenyhora and Arsenal, for whom there are no close narrative sources, for Earth there are antecedents in contemporary Ukrainian belles lettres and other literary works worthy at least of note: Olha Kobylianska’s Zemlia (Earth, 1902), On Sunday Morning For Herbs She Dug (1909)[224], Vasyl Stefanyk’s, short story collections, Kamminyi Khrest (The Stone Cross, 1900) and Zemlia (Earth, 1926)[225] and Andrii Holovko’s Buriian (Weeds, 1927)[226]. | ||

Poster for Dreyer's Joan of Arc (1928) |

|||

With regard to screenplay and print, all of Dovzhenko’s silent films come with their own version and translation problems. Due to Earth’s (1930) early censorship necessitated before its release, various existing prints add further complexity. There are at least six different versions of Earth circulating in East and West. Before Earth was released, it was reviewed by the Artistic Council of Ukrainfilm on February 26, 1930, and the Association of Revolutionary Cinema Workers on March 20, 1930[229]. On April 1, 1930, a week before its release, Demyan Bedny’s versified attack on Earth appeared in Izvestia resulting in Dovzhenko’s first set of pre-release cuts.

| Earth’s original North American release date was October 17, 1930 in New York,[230] six months after its April 8 Kyiv release. Between these dates Dovzhenko travelled with Earth’s assistant director, Julia Solntseva, exhibiting and lecturing on Earth in various European capitals[231]. Here, a young Siegfried Kracauer would write early on about Earth’s censorship and cuts[232]. | photographer30.jpg) |

||

Dovzhenko, his wife and co-director, Julia Solntseva & Futurist Poet Alexander Kruchenykh (1930), Photograph Alexander Rodchenko |

In its original North American release, Zemlia would be translated into English as Soil, the North American reviewers early on realizing the inadequacy of the provided translated title[233]. Later, the English name would shift to Earth[234]. Marco Carynnyk notes about the censored scenes:

The scenes were the replenishment of the tractor’s radiator, the fiancée tearing her clothes off in grief, and Vasyl’s mother in labor during her son’s funeral. They have been restored to copies of the film circulated since 1966.[235]

In a later memoir article, KINO VUFKU Ukrainian Paris correspondent and emigré avant-garde filmmaker, Eugene Deslaw, notes that the misunderstanding between Dovzhenko and Stalin began at the time of Earth. Deslaw relates that after a screening of the film at which Pudovkin and Eisenstein were present, Stalin pronounced that Earth did not tow the general line[239]. Through his recent request for changes in Eisenstein’s Old and the New (Spring, 1929; released, October, 1929), Stalin had a precedent for his interest in film surrounding collectivization.[240]

Perhaps the best that can be said about the better versions of Earth in the West is that they are not earlier VUFKU, Ukrainian, or the director’s cut, but post-humous reconstructions of a dupe negative with re-translated Russian inter-titles made in Krushchev’s time. In more than one of the censored sequences, inter-titles are missing.[242] While various censored copies of Earth exist in the West, the foundation of Dovzhenko’s original conception still holds up - a testament more to the integrity of Dovzhenko’s vision than preservation of the negative or ‘director’s archival version.

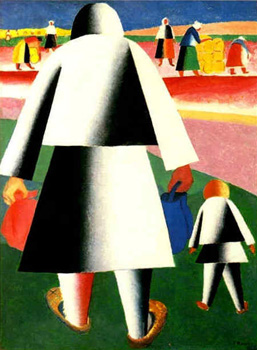

Harvest Time, Kazimir Malevich, 1929

Historical Background

Soil extends the message of collectivism farther into the province of the reflective, whither the film the world over must inherently progress. But in moving to the reflective, it becomes too personal a meditation, it becomes introspective where it should be prospective.

(Harry Allan Potamkin, New Masses, December 1930)[243]

|

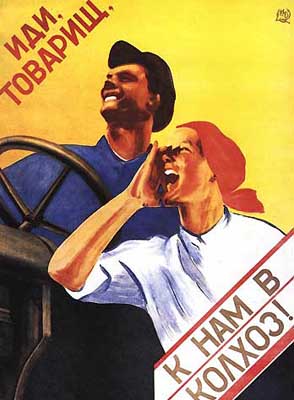

Earth takes place against the background of Ukraine’s collectivization or the transformation of agriculture from private-capitalist to collective socialist production. In 1921 Ukraine there were 193 voluntary collective farms; in 1928, 9,734, embracing 2.5 percent of all farms and 2.9 percent of the land[244]. The first version of the First Five-Year Plan for the Ukrainian SSR projected an increase to 12 percent of all arable land by 1932. Around the time Dovzhenko wrote and began principal photography on Earth, the final version of this first plan for collectivization was approved (April 1929) with an increase of 25 percent of the land projected to be collectivized. At the time of Earth’s post-production, these previous party plans were altered. In the Ukrainian countryside, forced collectivization was instituted. With the additional goal of ‘liquidating the kulaks as a class’, this altered plan radically increased the pace of collectivization. | ||

Soviet Collectivization Propaganda (1930). The poster reads "Hey Friend, Come with us into the Collective!" |

Robert Conquest comments:

In 1929 the Soviet Communist Party under Stalin’s leadership struck a double blow at the peasantry of the USSR as a whole: dekulakization and collectivization. Dekulakization meant the killing, or deportation to the Arctic with their families, of millions of peasants, in principle the better-off, in practice the most influential and the most recalcitrant to the Party’s plans. Collectivization meant the effective abolition of private property in land, and the concentration of the remaining peasantry in ‘collective’ farms under Party control. These two measures resulted in millions of deaths. . . Though confined to a single state (i.e. Ukraine), the number dying in Stalin’s war against the peasants was higher than the total deaths for all countries in World War I.[245]

By March 10, 1930, sixty-five percent of the Ukrainian farms and seventy percent of the land was collectivized. In light of Moscow’s new strong arm policy in dealing with Ukraine, there was a question. Would Earth be released? In the uncensored version of his later party autobiography, Dovzhenko would apologize for his misalignment with state policy thus:

I conceived Earth as a work that would herald the beginning of a new life in the villages. But the liquidation of the kulaks as a class and collectivization - events of tremendous political significance that occurred when the film had been completed and was ready to be released - made my statement weak and ineffectual. (At the Central Committee in Ukraine I was told that I had brought shame on Ukrainian culture with my work and my behaviour was called to order. A statement of repentance was demanded from me, but I went abroad for about four and a half months.)[246]

| The Soviet use of force in accelerating collectivization was excessive. Uprisings were provoked among the peasant populace and Stalin took a brief step back. On March 2, 1930, he published an article in Pravda entitled “Dizziness from Success”. Here, Stalin ordered forced collectivization’s end. On March 15, 1930, the peasants were permitted to resign from the collective farms and reclaim property if they so chose. Immediately following Stalin’s more permissive prescription, almost half of the coerced Ukrainian peasants left the collective farms. In this period, Dovzhenko’s Earth was allowed a brief, limited and hotly debated release (April 8 - April 17, 1930, Kyiv). |  |

||

| Soviet Collectivization Village Propaganda(1929): The Poster Reads "On our collective there is no room for priests or kulaks" |

Shortly after this time, Dovzhenko and his wife, Julia Solntseva, travelled through Europe demonstrating and speaking about Earth. From his letters it is clear that Dovzhenko had little desire to return to the situation in Ukraine. As his correspondence to Eisenstein in the United States suggests, Dovzhenko wished to emigrate [247]. In Ukraine, it became clear to the Bolsheviks that without force and coercion the collective farm would disintegrate. Ukraine’s overwhelming rural population would return to individual farming.

| Around the time of Earth’s first North American release (October 1930), forced collectivization was reinstituted. For both 1930 and 1931, Moscow raised the Ukrainian quota for grain deliveries by an impossible 115 percent. In the next harvest, at a time when left-leaning cinema clubs across Europe and North America were screening Dovzhenko’s images of abundance and western intellectuals witnessed presentations of bucolic fertility[248], a state-enforced famine of the Ukrainian rural populace occurred. |  |

||

Earth Still, Tilling the Land |

To generalize about Earth’s reception and different appropriation at this time in the West, Vlada Petric’s research on the reception of Soviet revolutionary films in America is useful[249]. Petric notes,

From the outset, Soviet silent films released in the U.S. raised two distinct reactions: one represented political hostility towards all Soviet productions without exception, the other was in sympathy with the ideological aspect of Soviet revolutionary films and quite favorable to them even when works were artistically insignificant. The Hearst press, which was mainly responsible for labelling the Soviet cinema “the Red Menace”, allied with a variety of political and religious groups in adopting a frontal attack upon Soviet film, as a part of their general program against Communism. . .On the other side the advocates of Soviet films were mainly young film-makers and theoreticians grouped around New York leftist publications, members of the Communist Party or the Socialist and Liberal organizations, who were ideologically along the same line with the subject matter of Soviet revolutionary films.[250]. . .The strategy chosen by The Daily Worker to ‘defend’ Soviet films from the political attacks of the Hearst press was, unfortunately, of the same blatant propagandistic brand as its ideological opposite. . .In fact, both antagonistic factions used Soviet revolutionary films as fuel for their political battle.[251]

During this period the United States had severed diplomatic relations with Lenin’s communist regime. The Hearst newspaper and magazine empire (i.e. Motion Picture Herald) was conducting a virulent anti-communist campaign. This would bloom into McCarthyism and the U.S. anti-communist witch hunts. Among western left-sympathizing intellectuals, journals and organizations[252], it was a badge of honour to valorize the Soviet Union through these films. News of the various republics’ dissent was ignored, discouraged or lumped with a retrograde nationalism.

At the height of the Ukrainian famine on July 27, 1933, the U.S. would formally recognize the Soviet Union, extending diplomatic recognition four months later on November 16, 1933. At this time, the death toll from the famine was around five million with conservative estimates figuring the death toll through this dark spring/summer/fall at roughly 25,000 people/day[253].

Bolshevik Harvest, Vasyl Kasian, 1934, Woodcut on Paper

On and off for the next few years after its production, Earth would be allowed release in North America and Europe by Soviet film sources[254] and used as a teaching tool in the early film/social history/aesthetics courses.[255] In contrast, a week after its limited engagement run in Kyiv, it would be withdrawn from Ukrainian and wider Soviet release.[258]

Contemporary opinion on Earth, even before release, was split. Many of the arguments against the film had less to do with the film itself than with what the film, in contemporaneous socio-political debates, was presenting, or, more often than not, omitting. The earliest critique placed Earth in line with Dovzhenko’s previous two silent features. Before its more general release, Kyiv’s Kino published sympathetic reviews of Earth by Mykola Bazhan and the western communist, Joris Ivens,[259] speaking of Earth as “the culmination of Dovzhenko’s aesthetic, a spiritual hymn to the earth’s fertility and larger philosophical meditation of life, death and the life cycle”.

Futurist poet, Geo Shkurupii’s journal, Avanhard Al’manakh, would publish notes by Dovzhenko on his working method and early screenplay fragments contemporary with Earth’s release, indicative of the borders in which Dovzhenko wished to place his film[260]. In this same issue articles were featured on De Stijl leader, Theo van Doesburg, the Czech avant-garde, modernist architecture, city planning and Der Sturm.

Editor, Geo Shkurupii, contributed a polemic essay that would have wider resonance. Entitled “The New Art in the Process of Development of Ukrainian Culture”[261], Shkurupii’s essay examined the avant-garde’s role in helping cultural currents overcome atavism and narrow domestic interest, and advocated a move towards ‘world proletarian culture’.[262] Here, he published Dovzhenko’s notes on his working methods on his soon-to-be released third feature, Earth.

|

On the other side of this fence and calling for Earth to be banned, the Moscow-based Russian Bolshevik papers, Pravda, Isvestia and the Russian Workers’ Club, trounced Earth as a pro-kulak film that would not instill in peasants the proper hatred and the demarcated class divisions of the Ukrainian villages such as those presented in Eisenstein’s Old and the New[263]. | ||

Poster For Eisenstein's Old and the New (1929) |

|||

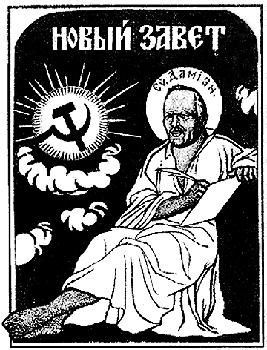

The most famous and known of the attacks and denunciations of the film was by Demyan Bedny[264] . Bedny’s versified articles would subsequently lead to Dovzhenko’s demonization as ‘pantheist, biologist, Spinozist and bourgeois nationalist’ precipitating a shift in his career’s fortunes.[265] In “The Philosophers”, Bedny wrote:

How many times have we quoted Lenin’s words: ‘For us the most important of the arts is the cinema.’ But the most important words have not been noticed. The most significant have not been noted; the most important is self-evident but ‘for us’ in our crucial battle, showing no pity to our enemies. . .advertisements cry out unceasingly, in honor of the cinema film Earth. Counter-revolutionary obscenity! That’s how low we have sunk.[266]

| According to Bedny, Dovzhenko had not painted the proper type of kulak infested village. He had painted an ambivalent picture. The party had expected a film that adhered to Marxist conceits that would visualize the economic necessity of ‘the liquidation of the kulak as a class’ so that ‘it matters not where or how they die’. What it received was a complex philosophical meditation on life and death. Ironically, even in his pedestrian versification, Bedny is correct in his argument. Dovzhenko does not present facile division between evil kulaks and goodhearted, simple-minded, party-obedient peasants but appropriates a slight narrative to accomplish something on a more complex level. |  |

|||

Bookcover for Demyan Bedny's Evangelist (1930). The text reads "New Testament" |

Early opinions were divided to say the least. Against a backdrop of complicated and intersecting debates, a historically longstanding Russian imperial / Ukrainian antipathy was commingled with a relatively new Bolshevik neo-imperialist / republics’ tension. These debates were also not unique to Ukraine but emblematic of the larger socio-political arguments contemporaneously occurring between the newly formed ‘republics’ and neo-imperial Red centre in Moscow[267]. It would only be later, in the face of international consensus, that official party opinion of Earth would make an about face. Attempting to erase notions of an earlier division, Soviet critique would distance itself from Bedny.

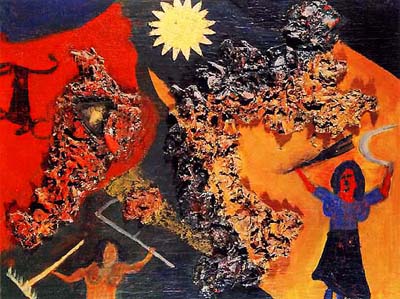

Harvesting, Mixed Media, David Burliuk, 1920's

The party-backed denunciation and orchestration of ‘the Moscow workers’ to rise

against Dovzhenko’s Earth has been noted.[268] Even

if to little effect, in VUFKU KINO’s final year there would be an effort

to counter this attack. A counter ‘ideological’ horizon of Ukrainian proletarian

opinion would be ‘rallied’ to state the workers’ opinions for Earth. The

Moscow ‘proletariat’ with the exception of one worker would be unified against Earth

as an unsuitable film for the proletarian masses. Kino’s assemblage of

Ukrainian workers’ opinion would diametrically mirror the Russian textual

construction. All of the Ukrainian workers, with the exception of one worker,

were for the suitability of Earth for Soviet screens[269]. In

the week prior to the film’s release, the debates regarding Earth had taken

on large political resonance.

Complex Presentiment, Yellow Half Figure against Blue Sky

Kazimir Malevich, 1928-32

Hegel, Skovoroda, Marx

How Dovzhenko came to be claimed both as a central showpiece of Soviet propaganda and an example of Ukrainian pantheistic spirituality, anti-Stalinism, and deep patriotism is one of the great paradoxes of his artistic development. Perhaps more. . .

(Myroslav Shkandrij, 1983)[270]

Earth opens with a series of longshots, sky against steppe. Wind moves over wheatfield in repeated lingering shots. Skies take two thirds of the frame as the noumenous unfolds. There is a serenity and harmony which opens the diegesis but also, oddly enough, for a communist and ‘officially’ atheist aesthetic, the uncanny feeling of a spirit invested in nature compassing a larger movement.

|

From the film’s beginning, distinctive forces harken beyond the socio-economic. There will be an undercurrent of imagery that acts as a visual dialectic and counterpoint to narrative and plot structure’s economic machinations progressing through Earth. In the predominantly rural Ukrainian landscape, Dovzhenko figures harvest rhythms and rituals through a grid of collectivization and ‘dekulakization’. Earth also dialogues with the work of the wandering philosopher (‘mandrivnyi filosof’), Hryhorii Skovoroda (1722-94)[272]. Dovzhenko significantly borrows from Skovoroda’s earlier appropriation of bucolic trope to present a philosophic cosmology.

Paraphrasing Skovoroda’s meditation on sowing rituals, the seed and kernel,

The whole world hides itself, as a beautiful blooming tree hides in its seed, then emanates from it. When a kernel decays in the field, new greenness comes out of it, and the decay of the old is at the same time the birth of the new; thus, where decay is, there is also renewal. [273]

|

||

| 1922 Memorial Sculpture to Hryhorii Skovoroda by one of the early VUFKU Avant Garde Filmmakers, I, Kavaleridze |

The progression of Earth’s opening visual images, wheat, sunflower seeds, family (in Ukrainian ‘simya’, homologous with ‘seed’), apple seeds, the dying grandfather, Semen (the name’s homology and etymology is analogous in both Ukrainian and English), is predicated on a complex meditation on the seed. For new life to arise, the seed must die and be transformed. These mystic truths are found in various cosmologic conceptions. What is unique in Dovzhenko is his way of philosophical conceit and appropriation of the steppe, countryside and ‘collectivization’ and ‘dekulakization’.

Wind over Steppe, Earth Still

Through a homology, the dying grandfather’s name, Semen,[274] associates him with the “movement of the seed” present in the film. At Earth’s beginning there are literally seas of wheat. A little later, a young girl’s head is metonymically associated with a sunflower filled with seeds. Vasyl’s kulak antagonists are presented standing unmoving, patronizingly spitting or wasting seeds. Later, the tractor illustrates Marx’s process of material production through a flurry of movement visualizing the seed’s trajectory into bread. In a similar manner, throughout Earth’s naturalistic imagery, Dovzhenko inflects the predominantly rural Ukrainian countryside’s images with a philosophic tradition. He foregrounds continuities and a line from Skovoroda to Hegel to Marx. Skovoroda paraphrasing Corinthians,

Sown rotten; raised fragrant; sown hard;raised tender; sown bitter; raised sweet; sown base; raised godly; sown senselesss and blind; raised all knowing and keen eyed.[271]

Other Soviet heroic period films dismiss the corruption and hypocrisy of pre-revolutionary religious institutions and clerics (i.e. Schub, Fall of the Romanov Dynasty, 1927, Bedny (above)) under the subject banner of Lenin’s injunction about the ‘opiate of the masses’. In Earth Dovzhenko plays with contours of a larger body of speculative thought, which may be described as a metaphysical dialogue.

Earth opens with a young woman in a traditional embroidered blouse next to a sunflower. While organized religion and the priest will be denounced, it will not be easy to ignore the grounding of pagan harvest fertility ritual and Judeo-Christian emblematic mysticism in Earth’s roster of poetic imagery and Marxist speculation. Semen is the grandfather of the film’s hero associated with old views of property, family, law, religion and morality. He is also emblematic of the pre-revolutionary older generation of emancipated Ukrainian serfs (1861). He is framed dying with his swaddling grandchild by his side. Every society is an interrelated totality in which no part can be understood in isolation.

Earth Still,

Semen's passing with swaddling baby

Opening Funerals

|

The atmosphere in Ukraine felt like the eve of a volcanic eruption. .

(Ukrainian Neo-Byzantine Painter Oksana Pavlenko on her invitation to lecture in Kyiv’s Higher Art Technical School, VKhuTeln, 1929)[286]

|

||

Sunflower, Georgia Okeefe, 1935 |

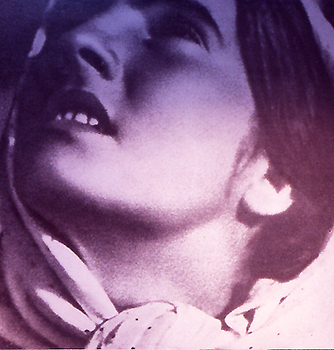

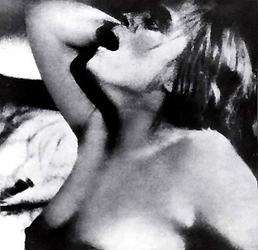

| Perhaps Earth’s most famous image is that of a close-up of a young woman, Dovzhenko’s wife, the actress, Julia Solntseva, next to a sunflower. The delicate eroticized dream-like placement is of a woman’s head next to a sunflower becomes a surrealistic analogue. Compare the Mexican painter, Frida Kahlo’s, hieratic Mexican still life’s or the American modernist, Georgia O’Keefe’s, flower series. They are good contemporary analogues for what Dovzhenko is accomplishing here. |  |

||

Still from Earth, Julia Solntseva next to Sunflower |

Earth invokes what may be called a seminal poem of the Ukrainian renaissance , Pavlo Tychyna’s, “Sunny Clarinets”[288] continuing Dovzhenko’s series of epic allusion, . Like Earth’s opening sunflower, Tychyna’s Sunny Clarinets comes to terms with a violent revolution’s disjunctive events through a connection with a sunflower and neologism ‘sunny’, or ‘sunflowery clarinets’[289]. Sunny Clarinets opens:

|

Neither Zeus, nor Pan, nor Dove-Spirit just sunflowery clarinets, I am in dance, movement’s rhythmicality eternity’s within - all the planets.

I was - not I. Just illusion, dream Encircling - ringing notes of darkness’s fecund garment and well-wishing hands.

I awaken - already I am you Over mine, below mine blaze worlds, worlds race in musicality’s river.

I watched, I bloomed Planets accorded themselves I recognize, You are not Wrath just sunny clarinets.[290] |

||

Dovzhenko's Cubo-futurist portrait of Ukrainian poet, Pavlo Tychyna (1924) |

Tychyna’s bucolic jazz-like image is a synaesthetic trope for a sunflower, “Sunny Clarinets.” The new post-revolutionary world can no longer be compassed by a Hellenic Greek Apollonian cosmology (“Neither Zeus”), Orphic Dionysian mysticism (“Neither Pan”) nor a Judeo-Christian cosmology (“Not Dove Spirit”). Tychyna announces that his revolutionary vision will be compassed through a more modest, ‘sunny clarinet’ grounded in Ukraine’s fecund soil.

| Earth’s symbology is also through the presentation of Dovzhenko’s new wife, Julia Solntseva, and the homology her name makes with the sun (Sontse). Gilberto Perez comments, “The woman’s immobility comes across as the opposite of passivity: it is a resistance to being swayed, an assertion of her intrinsic energy, her own intensity, before the surrounding energies and intensities of nature”.[291] Tied to literary, contemporary aesthetic and symbolic sources, Dovzhenko’s invocation is connected to the modern but also the personal and archetypal. |  |

|||

Three Ages, Fedir Krychevsky, Kyiv 1913 |

Continuing Earth’s first extended sequence, four generations of a village family gather in an orchard. An aged peasant, Grandfather Semen, spends his final moments mmong his great grandchildren. In contrast to Eisenstein’s stereotyped presentation of the old in the Old and the New (1929): fat, ugly and indolent ‘kulaks’ and dirty and mentally deficient rural peasants in need of the Comintern’s guiding hand, Dovzhenko presents a different picture. Joking, eating and playing among heavy laden appleboughs and fallen fruit, four generations of a family are illuminated in halo-like glow. The ‘seliany’ (literally, villagers, not ‘peasants’) are presented with reverence and funereal dignity.

Still from Earth, Apples on bough

|

Harkening to the first French avant-garde or impressionist filmmakers [292] of the 20’s, Dovzhenko presents this scene like much of Earth, surrealistically and through soft focus cinematography. Through a conflation of classical and Judeo-Christian iconography, the scene foregrounds an apple tree, death, knowledge and fallen fruit. Before Semen is to die, there is a commingling in inter-title dialogue of an analogous transition between classical/Christian world views lost in the inter-title English translation. One cosmology passes, another ascends. | |||

"Woman Under Apple Tree", Oksana Pavlenko, 1929. |

||||

Semen’s old friend, Petro, jokingly tells him, “Let me know where you are over there,

Heaven or Hades”[293]. The

intertitles mix not Heaven and Hell but two cosmologies, a Christian heaven with

an earlier classical, pagan, Hades. In 1930, the mixing of metaphoric systems

would not have been lost on contemporary Soviet audiences. During the last ten

years, they had experienced a great disjunctive rupture and revolutionary

societal turn. Dovzhenko will place Earth in a similar transitional set

of culturo-temporal coordinates. He foregrounds not simply the rupture to new

aesthetic forms (i.e. the cinema) but also film’s displacement, appropriation

and continuity with antecedent media.

Expulsion from Paradise Maria Syniakova, 1916

Modernist Iconology

|

Do not trample on the rye, it is alive! (Mykhailo Boichuk to his sister Kateryna on the winter wheat)[294]

|

||

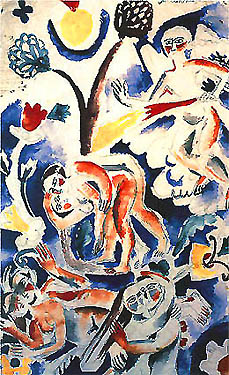

| Marpha and Vanka at Harvest, Kazimir Malevich, 1928-32 |

Earth is composed of a series of classically arranged iconic portraits. Still-lifes and close-ups of different generations of villagers are presented within a larger visual meditation on death, passing of the old and coming of the new. Like the Eastern Orthodox Byzantine icon, Earth’s figures are presented in two dimensional flat tableaux. Rejecting secondary perspective, there is a concentration on the close-ups, emphasizing an aesthetic that Gilberto Perez has characterized as, “all in the foreground”. Perez nuances the ‘painterly’ resonance in Dovzhenko’s aesthetic:

Dovzhenko emphasizes not how things look from a certain viewpoint, under a certain light, submerged in a mise-en-scène, but what Bernard Berenson called ‘the corporeal significance of objects.” Like Giotto, and like his successors in the Italian and northern Renaissance, Dovzhenko strongly engages the sense of touch in images that vividly render the fullness and self-sufficiency, the rounded steadfastness of solid forms. The settled, stable quality of Dovzhenko’s images - one can imagine many of them going on indefinitely - contrasts with the restlessness one finds in Eisenstein or Murnau, filmmakers who, for all their differences, have a quality of the baroque. Something Adrian Stokes said about Piero della Francesca could as well be said about Dovzhenko: compared with his images, those of all other filmmakers are as sea to land. Giotto and Perio may be characterized as painters of the foreground. . .[295]

| To achieve an effect of ‘all in the foreground’, Dovzhenko relies on spatial fragmentation and isolation from the context of a larger space that gives the aesthetic an equality and equipoise not present in other Soviet heroic era filmmakers. In Dovzhenko’s opening presentation and later in the meeting of Opanas with the Party Cell, Vasyl’s death, the Bucolic Lovers and Opanas confronting the priest, figures are presented in halo-like hagiographic close-up. Like the Byzantine icon’s spatial dynamic, background loses perspective. Emphasized instead is a play of line and contrast of soft-focus light surrounding each of the figure’s visage. Halo-like and essentially plastic in nature, Earth’s portraiture contributes to the aesthetic’s elemental mode. |  Earth Still, Opanas with Party Cell |

||

|

|||

Slavic Byzantine Icon, St. Nicholas, 14th C. |

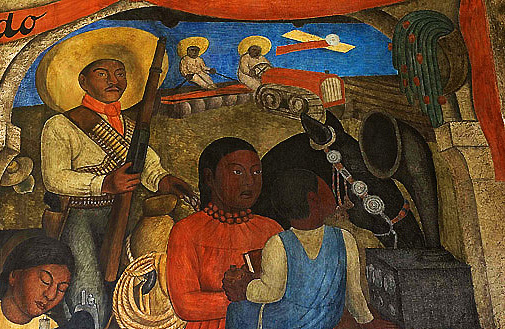

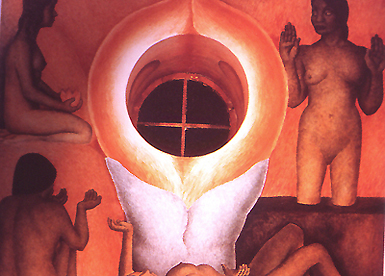

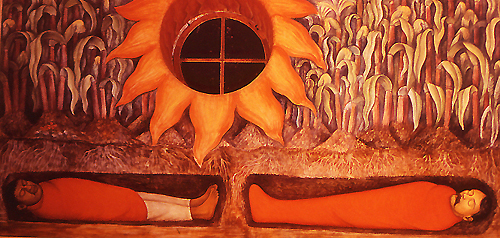

Earth explores iconology on a hieratic level different from Arsenal in more than degree. Dozvhenko lends ecclesiastic reverence to the earth and larger rural populace’s struggle for social justice. A parallel for what Dovzhenko is accomplishing can be found in Diego Rivera’s compatriot, the Mexican muralist, Jose Clemente Orozco’s fresco “The Family” (National Preparatory School, Mexico City, 1926) . Here, a similar rural family to Earth’s is portrayed through codes of neo-Byzantine iconography. In a similar funereal situation and encompassed by revolution, urbanization and modernity’s sea-change, a family bears witness.

|

|

||

Family, Jose Clement Orozco, 1926 |

Liberation of the Peon, Diego Rivera, 1923 |

Contemporary to the period and also drawing on Byzantine iconographic code to present the revolutionary event’s profound nature for the peasants would be the work of the Mexican muralists. For example, compare Diego Rivera’s “Liberation of the Peon” (1923, Ministry of Education, Mexican) or “New School Frescos”, which similarly bathe the Mexican peasant in golden light.

| Largely filmed in close-up or head shots, the emphasis on Byzantine iconology and its head-of-the-saint foregrounding will be present throughout Earth. Not so much presented as reaction shots, the close-ups of the family’s various generations’ faces in Earth are close to Dreyer’s Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) or Hugo Munsterberg’s or Bela Balasz’s contemporary prescriptions about micro-physiognomic gesture and film specificity[296]. Like Dreyer’s close-ups of Joan, physiognomies are presented with dignity, as visages of spiritual austerity. Like Bela Balasz’s early distinctions between theatrical and cinematic possibilities, Dovzhenko’s aesthetic harkens to notions surrounding medium specificity . |  |

||

Still from Dreyer's Joan of Arc, 1928 |

|

|

||

Opanas still, back to Camera |

Earth Still, Iconic Closeup |

Cinematographically, in this extended opening scene Dovzhenko plays with the rules of visual grammar, specifically the ‘eye-line match’ and ‘matching screen direction’. In cinematographically illuminated icon-like religious glow, Earth’s opening portraiture is presented in contrapposto to well-established codes of film grammar. When two camera shots show different persons looking at each other, the first person must look screen right and the second person screen left. If both figures look in the same direction in successive shots, the viewer inevitably has the impression that the figures are not looking at each other and will suddenly feel lost in screen space. Noel Burch comments that, early on, the Soviet heroic period’s directors began to glimpse what these rules implied: that only what happens in frame is important; that the only film space is screen space; that screen space can be manipulated through the use of an infinite variety of possible real spaces, and that the ability to disorient the viewer may take on epistemologic coordinates.[297] Burch comments about Dovzhenko’s opening scene’s subtlety:

It was the Ukrainian master Alexander Dovzhenko, in the opening sequence of his greatest film, Earth (1930), who went on to show how it was possible to construct, with classical spaciality, an ambiguous diegetic space, in the sense that it is essentially and disturbingly uncertain. . .The characters are never seen together in the same shot; they are linked only by their eyeline exchanges. A close reading of this sequence shows a whole series of discrepancies which actually render impossible a reading of diegetic space in keeping with the traditional system of orientation: ‘in the place where’ the orientation of a glance from the old man had enabled us to situate this or that character, we now encounter another; in the course of another series of apparent reverse-angle shots, we encounter still another character ‘in the same place’, and yet, as far as we are able to judge, the hieratic stillness of the scene has been preserved throughout.’ At other moments a shot of a field of wheat seems to be located in an impossible space. [298]

There is a disorientation presented through film grammar’s codes that give rise to questions, “Who are these people - kulaks or peasants? In what context should they be viewed?” Dovzhenko sets up ambivalence through the montage. In close-up, crying and flailing their arms four old women lament. At their sides, men sit in despair. Following Semen’s death, through metonymy and the Kuleshov effect, the viewer naturally makes the association of the women’s grieving with Semen’s death. Surprisingly, the women are not lamenting Semen’s death. They are Ukrainian kulaks.

|

||

Dovzhenko and crew during Earth's filming, 1929, Peasant garb. Centre Dovzhenko, immediate right cinematographer Danylo Demutsky immediate left, asst. director Lazar Bodyk, far right, Vasyl, Semen Svashenko, far left, Khoma Petro Masokha. |

The sequence illustrates Dovzhenko’s ambivalent attitude toward the situation occurring in Ukraine, circa fall/winter 1929-30. The party cell, Marxists and Vasyl wear conventional “Soviet” worker garb. The ‘kulaks’ are adorned in embroidered traditional shirts, which through ‘dress code’ signal an alternate orientation. This make for a complicated epistemologic intermingling because of the immediate cutting with the grandfather’s death.[299]

In Earth, Dovzhenko’s aesthetic mode is syncretic, iconic and complex. There are parallels harkening to the ascendant French surrealism. There is a fascination with a dream playing out through the film. Dovzhenko references impossible spaces by setting up eye-line matches and cuts that exceed possibility’s boundary. Earth references the hereafter’s unknowable surreal space by a type of visual paradox. Through a purposeful eye-line set-up of expectation to objects, people or events that cannot be, Dovzhenko pushes silent cinema’s grammatical borders toward surreality.

In 1930 international surrealist currents were at their apogee. Striving for a union with international communist and revolutionary aspiration, Benjamin Peret’s and Pierre Naville’s journal, La Révolution Surréaliste, advocated linking the surrealist breakthrough with the communist upsurge[300]. In a historical work on the USSR’s formation, Aragon would theorize ‘how the dream was to be engendered’ to achieve collectivization of the countryside on a social scale.[301]

Dovzhenko’s Eastern European dialogue with surrealism was not lost on the surrealists. After viewing La Terre, the surrealist poet, writer and communist, Aragon would write in “Roman Inacheve” of Earth’s aesthetic, delineating affinity with the surrealist agenda.[302] Breton, Eluard and Aragon would advocate that surrealism become more political and communism more surreal in attempting to bring the revolutionary utopian valence of surrealism and communism together. In his memoirs, Ilya Ehrenburg would attest to the French avant-garde’s affinity with Earth’s orientation: “When Malraux was in Moscow (1934), the first thing he hoped to do was to make a film based on one of his novels and discuss this production with Dovzhenko”.[303]

In an Eastern European orbit and constituent of this haunted dynamic of forces is the regional inflection and dialogue that Dovzhenko presents with this ‘different’ surreality. Having room for further comparison with Earth is this ‘other’ surreality’ especially figured in less discussed ‘other’ regional modernist configurations such as Diego Rivera and Frieda Kahlo’s surrealist inflected muralistic searches, the Spanish avant-garde filmmaker, Luis Bunuel or cinematography of Gabriel Figueroa[304]. |

|

||

| The Other Surrealists: Trotsky (sitting), his wife, Natlia Sedova,the Painter Diego Rivera (back right), his wife, the Painter, Frieda Kahlo, Behind Kahlo, the French Surrealist, Andre Breton |

Earth’s muralistic aesthetic has parallel with these less spoken about paths haunting struggles of national emancipation and social revolution. Ripe for comparison are Kahlo’s later pregnant still lifes “Fruits of Life or “Viva La Vida”[305] . Rooted in regional specificity, Dovzhenko’s Earth resonates with this less spoken about social and surrealist confluence and modernist eroto-political set of themes.

|

|

||

Earth Still, Danylo Demutsky's Soft Focus Apples |

"Viva La Vida" Frieda Kahlo (1954) |

In his later literary adaptation of the Earth screenplay, Dovzhenko similarly alludes to these neo-byzantine surrealist coordinates and a series of modernist movements ascendant in the period. Beginning Earth’s later screenplay adaptation, Dovzhenko writes:

Did it really happen, or was it a dream? Have dreams merged into memories, and memories of memories - I’m no longer sure. I only remember that grandfather was very old and I remember that he used to look like one of the images on the icons that graced and guarded our old house.[306]

Dovzhenko’s surreal iconic visual depictions are more explicit in the screenplay adaptation. Grandfather Semen is described in a set of dream-like tropes connecting him with images from Byzantine iconology,: ‘the gleam of his saintly white beard’; ‘all white and transparent from age and goodness’; ‘the way he lay there, like a figure in a painting’; ‘he even seemed to glow a little; ‘at least it seemed that way to me because it was Sunday, and some other kind of holiday as well .[307]

Earth Still, Grandfather Semen's Passing

Grandfather Semen’s passing is surrounded by a peaceful family close-up. In Dovzhenko’s presentation, the images lead to questions regarding a wider contextualization of villagers. Are they kulaks? Ukrainian peasants? Bolshevik communists? Ukrainian nationalists? Repeatedly over the years, in notebooks, essays and addresses, Dovzhenko would emphasize not ‘class types’ in his iconic portrayals but originary codes of personal realism:

Who are my heroes? Father, Mother, Granddad, and Myself. I am Vasyl, Schors, Bozhenko, and Michurin. It is my Granddad who dies in Earth. Shkurat is my father. I am the boy who sits with the girl by the house.[314] . . .The grandfather in Earth is my own late grandfather, Semen Tarasovych Dovzhenko, an honest, kind, and genteel old salt trader.[315] Father Panas (Earth’s Father) - the Ukrainian villager -this is in fact my father, Petro Semenovich Dovzhenko, who in his sixty-seventh year of his life joined the collective.[316]

In Earth, Dovzhenko creates a model, an impression of an idealized reality of a bucolic mode of life that paradoxically never existed but now is passing away. Through Earth’s presented images, there is the sense of lives halted, freed from future destiny. In joining cinema, iconic portraiture and his own personal mythopetic through reference to Byzantine Eastern Orthodox iconographic code, in Earth (1930), Dovzhenko would construct his own surrealistic death mask of an old way of life.

Harvest Still, Earth

Ritual Sacrifice

The cruelties of the past filled needs which we can satisfy now in ways other than those of savages.

(George Bataille, Sacrifice)[317]

From early on Dovzhenko would emphasize qualities associated more with the icon, classical art historical motifs and ‘aura’ of art than spectacle or distraction. Through Earth’s narrative there is a figuring of a pseudo-typological communist displacement and reconfiguring. The communist Christ, Vasyl, brings a new way of life to the village. Paradoxically, for this new way of communal life to be born, Vasyl must be sacrificed.

Vasyl's death among the apple boughs, Earth

In Earth and Arsenal the play with death and the noumenous is with Eastern Orthodox Byzantine iconographic code. Arsenal would show, “Lives of the Saints”, sublimated and displaced onto the Soviet Stakhanovite hero. A constituent part of the period was a contemporary (re)inflection of Byzantine portraiture and (re)examination of Byzantine iconology’s origins, not so much as a way of discarding religious form but an allowance of a more distanced, incisive and parametric critique[322].

|

|

||

| Eve, Maria Syniakova, 1916, Neo-Byzantine Primitivism | Creation of Man, Marc Chagall, 1921 |

Until the Soviet Union’s fall, the revolutionary period was a height of critical and creative redivivus of the previously sacred and unapproachable Byzantine icon. The Russian painter, Alexander Strelkov, published the first and still ambitious syncretic polyglot exploration of the mummy portraits, Faiumskii Portret[323]. Described contemporaneously by the English as the patriarch of Eastern Orthodox Byzantinists, Nikodim Kondakov’s early proto-deconstructive ‘art historical’ work into the icons’ origins was widely translated[324]. Kandinsky, Yermilov, Chagall, Syniakova and Jawlensky drew inspiration from primitive iconic color schema. Tatlin and Goncharova began as icon painters.

Birth of Christ, Natalia Goncharova, 1916

In Eisenstein’s concurrent unfinished masterpiece, Que Viva Mexico, there is a similar conflation of tropes (i.e. Day of the Dead, Catholic Cults of the Saints, anthropological questions regarding religious origins) but also sympathetic iconic depiction of rural masses common to Earth, but proscribed by the period. In the extant footage from Que Viva Mexico, there is a sense that Eisenstein is sublimating, projecting and displacing what was officially impossible to portray in Old and the New and what Dovzhenko was denounced for courageously portraying in Earth.

Still from Eisenstein's Que Viva Mexico (1931)

Neo-Byzantine Modernists

|

Egypt or the renaissance, a Novgorod icon or a piece of African folk art - all this is irrelevant. Art seeks to root itself in the people among whom it has developed, but as soon as a work has been created, it becomes international. (Mykhailo Boichuk, Lectures on Monumental Art)[341]

|

||

Harvest, Zinaida Serbiakova, 1915, Oil on Canvas |

| Earth’s images resonate with what Appollinaire had named in 1910 the neo-Byzantine school[330]. From Earth’s beginning there is allusion to Timofii Boichuk’s period tempera, “Apple Picking” (1919) (see above ) and the Ukrainian monumentalists’ Kyivan revolutionary public frescos . In a bucolic setting there is a similar conflation of classic Judeo-Christian and Byzantine iconic motifs. Advocating a fusion of two influences, primitivism (as expressed in folk culture) and Byzantine art, the Boichuk school formed the largest grouping in ARMU[331]. During Ukraine’s independence (1918), Boichuk had taught at the newly created Academy of Arts at which Dovhzneko was enrolled[332] and Dovzhenko’s early essay, “On the Problems of Visual Art” (1926), shows familiarity with the neo-Byzantine school[333]. The primary exponents of the neo-Byzantine school are valorized; its prescriptions for the contemporary direction of Ukrainian modern fine art validated.[334] |  |

||

T. Boichuk, Near the Apple Tree, 1919-1920 |

At the same time, Dovzhenko is satiric of Soviet heroic realism (what became Socialist Realism). In Earth, this satire is evident. Oxen, horses, swaddling new-borns and watermelons are given Soviet heroic style camera decorum .

|

|

||

Earth Still, Heroic Angles, Awaiting the Tractor |

Earth Still, Heroic Angle Horses Awaiting Tractor |

The centre tableau in Earth’s portraiture is the scene of the tractor’s arrival. In this neo-Byzantine collectivization mural, the sequences surrounding the tractor make up Earth’s central panels. The film possesses little movement before the tractor arrives. Characters are shot in close-up with little depth of field. Landscapes and apples within the orchard have been organized as a series of iconostatic, still-life tableaux to be read iconically and with a painterly eye for composition rather than inter-frame movement that suggests relationships, are montaged.

Detail from Diego Rivera's Mexican Frescos, Dept of Education (1923-1930)

Like Rivera’s public multi-panelled period Mexican frescos (1923-1930), through Earth Dovzhenko constructs a mural of the collective. Boys and girls sit on rooftops; young married women sit on logs; men wait in a state of anticipation; oxen are shot not lowing but from conventional Soviet heroic style high angle awaiting the tractor’s arrival. From a state of ‘historical’ stasis, a collective entity emerges. Close to Diego Rivera’s Marxist iconographic decoration for the Chapel at Chapingo, the panels taken together in Earth form an iconostatic shrine to agrarian abundance and the land’s fecundity (fig. 50). Like Rivera’s heterodox Marxo-philosophic erotic chapel, Dovzhenko’s visual shrine is to the earth’s fecundity.

|

|

||

Germination, Chapel at Chapingo, Diego Rivera, 1926 |

Still from Earth's Final Montage |

Through a set of thematic panels and tableaux, this fecundity is presented in a Marxist yet also heterodox, eroticized metaphoric Judeo-Christian context. Parallels to what Dovzhenko is rearticulating can be found in the Mexican monumentalists (Rivera, Orozsco, Siqueiros). Similar to the Mexican muralists’ public frescos of the mid to late twenties (i.e. the decoration of Mexico City’s Ministry of Education, 1923-28; Chapel at Chapingo, 1926), Dovzhenko synthesizes the national subject matter with Byzantine iconography to create an extraordinary set of kinetic panels.

Desmond Rochfort comments about the similar development of Mexican muralism in this period,

The development of Mexican muralism can be seen to grow out of a Mexican cultural renaissance, the roots of which were clearly present and developing before the revolution. This renaissance synthesized with the political revolution to form a unique relationship between a tide of radical national politics and a cultural rediscovery. . . Nowhere is this better expressed than in contemporary mural painting. To understand this art is to consider and submerge oneself in the spiritual, social, political, philosophical and historical problems of our time, not only in Mexico, but in the panorama of world culture.[342]

Reflecting religious, spiritual but also social traditions and national aspirations, the sentiments that permeate Dovzhenko and the Mexican monumentalists’ works valorize agricultural populations living in a longstanding colonial or imperial shadow. As poetic narrative of a revolutionary impulse, the Mexican Muralists statically and Dovzhenko kinetically create syncretic visual syntheses of agrarian cultures and traditions.

Mechanization of the Country, Diego Rivera, 1926

There are similarities with Earth’s central tractor panel in Rivera’s “Mechanization of the Country” (1926, Ministry of Education, Mexico City ), (fig.51) . In both representations, the hero, is figured in high angle presentations, master of technology. In Rivera’s mural, hydro-electric dams and power stations form the background. Oxen look on amid telegraph poles in Earth. In Rivera’s “Mechanization” a Mexican peasant ploughs up land on a tractor. In Earth, Vasyl rides high as the tractor ploughs through fields . In Rivera’s mural, centre frame, a peasant maiden heartens the rise of two stalks of maize. In Earth, young peasant women bend over to gather up the cut wheat stems into burgeoning sheaves.

Earth Still, Vasyl Bringing Mechanization to the Collective

Wind blows intercut with the movement of soil being turned,. Men shovel or throw grain onto conveyor belts. Wheat is ground to flour, flour kneaded to dough, dough baked to bread. Through montage and close-up, this production process is presented in terms of an appropriation of geometric composition and abstraction of form. In a montage that demystifies and visualizes material production’s process, the village works together with the technology.

Kazimir Malevich, Taking in the Rye, 1912

Dance of the Dead

|

The grove’s wind no longer dances, it rests at night, to reed grass turning, asking softly: All round, who’s this combing braids? Who’s this? All round, who’s this tearing braids? Who’s this? (Taras Shevchenko)[344]

|

||

Earth Still image, Vasyl's Final Dance |

Dovzhenko’s produces visual poetry in Vasyl’s final dance,. With regards to this scene’s formal stylistic eloquence, critics comment on Earth’s limited camera movement and Dovzhenko’s acute sense of its epistemologic implications. When the camera does move, the movement is disconcerting.[345] Camera retreating before him, Vasyl begins his penultimate nocturnal dance.

In an early historical work on film aesthetics, Celluloid: The Film Today [346], Paul Rotha describes the eloquence of this scene that struck a range of commentators. Attempting to capture Dovzhenko’s lyric, Rotha comments:

Quietness again, evening draws on. Rest and peace descend after the labour of the day. Shadows grow long across the screen. It becomes difficult to see. Layers of creeping mist circle over a pool of water. Groups of men and women stand together, holding hands in the cool of the evening. Supreme in safety, a girl leans her head against her lover’s breast. Fingers are entwined with fingers, rough with the touch of corn-stalks. There is perfect stillness in the dusk. Away in the distance, the Kulak’s son is reeling home, dancing drunkenly from side to side of the road. A neighbour follows and tells him that the tractor has been driven across his fields. Elsewhere, Vassily is returning to the village, his heart filled with joy at the success of his day. It is now almost dark and deathly silent. A horse grazes in the dew strewn grass. Vassily stops and wonders as his soul is filled with the greatness of life. Gradually he begins to dance, gently at first and then quickly, movements of joy and happiness. Faster and faster he twirls in the dusty cloud at his feet, advancing set by step up the winding white road. The camera retreats before him as he throws his whole heart into this dance of passionate joy, until he comes near the lights in the village. Suddenly, at the height of his movement, he drops fast in the dust. The startled horse lifts its head. Vassily lies dead.[347]

| The camera’s retreat effect in this sequence suggests the uncanny. Before Vasyl’s night dance, the young lovers were in close-up two-shot soft-focus secular reappropriation of an iconic tableau. The pair were gazing at a giant oak, a giant night sky harvest sheaf. |  |

||

| Earth Image, Couple-Close Up |

With regards to Vasyl’s dance, there is a cutting between matched shots. This signals transitions in time in conventional film grammar. It articulates the hieratic in Dovzhenko’s visualization. Commenting on these sequences’ visual emblematic qualities, Noel Burch speaks about ‘times’ complex rearticulation,

Certain shots, though more closely related to an ‘emblematic’ space/time than to the diegetic space/time proper, nevertheless continue to entertain subsidiary links with the latter (witness the series of shots indicating the passing of the seasons, the quasisymbolic sequence of ‘the lovers’ night, or the shots of the young woman standing by a sunflower. Conversely, other moments which are firmly anchored in the primary diegesis (such as Vassili’s famous dance-and-death or his father’s night of mourning) seem to partake in turn of those emblematic shots, tending to suspend the moment of the diegesis. [348]

As in Zvenyhora and Arsenal, the character of Vasyl has been presented in contrast to another, the kulak’s son, Khoma Bilokin. Throughout the film, Khoma has been presented in traditional shirt, effeminate, indigent and religious (observing church holiday). He is also presented as young and with interests in the land. In name, he is tied with Khoma Brut, the young philosopher from Gogol’s tragic mystery, “Viy”. Vasyl and Khoma are anti-types as in the trilogy’s previous films.

|

|

||

Khoma in Traditional Embroidered Shirt |

Khoma's final parody of Vasyl's Dance |

Dovzhenko’s division is symptomatic of the period’s larger cultural coordinates.[349] In Zvenyhora the nationalist commits suicide. In Arsenal, the film ends in Tymish’s agonized silent scream. Here, the Ukrainian kulak kills his communist double. He is struck down by a figure who may be termed his shadow. There can be no union between these forces. The consummation that does result involves a sublimation and displacement into violence and death. Insofar as there is a synthesis of competing forces, it is through a strange Christian/pagan harvest sacrifice ritual and later, ‘incorporation’ of the communist and what he has brought into the body politic of the rural collective.

Blood of the Revolutionary Martyrs Fertilizing the Earth, Diego Rivera, 1926

Vasyl’s death ensures the future abundance of the larger collectivity or commune if one reads this as a pagan harvest sacrifice ritual. In Vasyl’s death, what he represents is incorporated into the village. The newly constituted elements of this cosmology are incorporated into the rural collectivity. Dovzhenko’s vision is utopian and hopeful. Earth calls for a quasi - Christian/pagan harvest sacrificial incorporation of the communist ethos into the rural worldview and body politic. History and Stalin would show otherwise. Through a Soviet state-constructed famine and genocide, this incorporation would work in the opposite direction.

Sunset Sunflower for Vasyl's Funeral Montage

Closing Funerals

|

||

Earth Still, Closing Funeral |

Similar to Earth’s opening, Dovzhenko ends with a funeral. Young

women carry flowers. The priest prays alone in an empty wooden church. A woman

gives birth. The commune comes together. Celebrated,

censored, criticized by Eisenstein for its longshot of Vasyl’s naked grief-stricken

lover[350], Earth’s

ending is a complex montage - a birth but also a death. If up to now the film may

be seen as setting ground for an eschatologic presentation, the collapsing of

levels now occurs through montage. The outer landscape takes on a noumenous hieratic quality in a sequence that may be described as complex

pathetic fallacy.

Earth concludes with the body of the village coming together to sing new songs. In silent cinema variant, Dovzhenko’s final synaesthetic analogy is aural. The screenplay adaptation reads:

Songs flowed into the procession from all the roads and lanes without a break like streams into a great river - old cossack and oxdriver’s refrains, songs about labour, love and the fight for freedom, and new Komsomol songs, the ‘International” and ‘The Testament’, “The Falcon and the grey-winged eagle have joined arms. Hey! My brother and comrade. . .and then once more, ‘We’ll all go into battle for the power of the Soviets”. They all flowed together into a single shattering sound.[351]

|

|

||

Mykhailo Boichuk Harvest Festival in the Collective, Public Fresco

|

Earth Still, Vasyl's Funeral

|

Zvenyhora’s Duke of Ukraine suicide speech falls on deaf ears. Arsenal ends in a silent Munchean scream. Earth figures the collective coming together and singing in a gesture that harkens again to the silent cinema’s medium limitation. The synaesthetic conceit foregrounds silent film’s specificity. The weight of this larger set of threshold transitions is conveyed through the visualization of a medium specific threshold boundary (silence/sound), .[352]

Like Rivera’s Chapel at Chapingo, Earth’s larger tableau has been one of paradox, ambivalence and surrealistic irony. On the one hand, Dovzhenko has presented a ‘hymn to a new life’. On the other, the only way this could be figured was through a line of funerals, deaths and foregrounded funereal aesthetic. Like Rivera, Dovzhenko has striven towards constructing a visual shrine to a materialist philosophy, politics of collectivization and earth’s fecundity. Paradoxically, the images evoked have been through an essentially Judeo-Christian set of tropes and overt mythologic borrowing.

|

|

||

Censored Images from Earth's Final Montage |

Vasyl's Grief Striken Lover |

Earth’s closing sequence has few parallels in silent cinema in its noetic complexity. Dovzhenko envisions a poetic pictorial synthesis against

a modernist backdrop of the Ukrainian cultural renaissance’s international

aspirations. He fuses a

deeply religious and spiritual

tradition of a historically rooted agrarian culture with a modernistic awareness of ‘collectivization’ and ‘dekulakization’.

Apples on Ground, Earth

Earth concludes with the presentation of paradisaical vegetation - wheatfields, apples, melons, a voluptuous fecundating rain. Apples are restored to the branch outside the town. The fruits of the earth glimmer in newborn splendor washed by falling rain. It is hard not to feel prophetic catharsis. Compare Dovzhenko’s visualization with the revelation of the Divine to Isaiah:

For as the rain cometh down and the snow from heaven, and returneth not there but watereth the earth, and maketh it bring forth and bud, that it may give seed to the sower and bread to the eater[354].

| Earth concludes between coordinates of icon and dream. In the film’s final

image, Vasyl’s lover, Natalka, in soft-focus close-up awakens as if from a

dream. The shot is matched with an earlier shot in the film. With the rest of the

young villagers and in the safety of Vasyl’s embrace, Natalka had found a brief

security under the harvest moon. Like so many period Hollywood endings,

the idealization is ‘happily ever after’. Earth’s final context is left in the foreground, enigmatically iconic,. This is a space of ‘l’amour fou’, between icon and dream, figured through the cinema’s transitioning

representational practices.

|

|

||

| Earths Final Closeup |

Kiss, Vsevolod Maksymovych, 1913, Kyiv

Introduction |Zvenyhora (1928) | Arsenal (1929) | Earth (1930) | Conclusions|

Filmography | Earth Chronology | Bibliographies| Contact

Notes

[221] Dovzhenko, Alexander. Tvory: 5, ed. M. Rylsky Kyiv: Dnipro,

1966. p. 204.

[222] Skovoroda,

Hryhorii. As translated in Lindmark Black, Karen. The Sources of the Poetic

Vocabulary of Grigorij Skovoroda. Ph.D. Dissertation. Bryn Mawr College,

1975. p. 256.

[223] To note, kulak is the Russian pejorative for a

‘rich, well-to-do peasant’. It’s Ukrainian equivalent is ‘kurkul’. Because, the

Earth versions in the West are Russian titled and the secondary

literature exclusively making use of this term, kulak will be used here.

[224] See Fylypovych, Pavlo. Introduction to O. Kobylianska.

V Nediliu Rano Zillia Kopala (On Sunday Morning For Herbs She Dug,

originally, 1909). Republished Buenos Aires, 1954. lv. Formal narrative

parallels have been explored between what early Ukrainian modernist, Ivan

Franko termed Kobylianska’s impressionistic masterwork and Dovzhenko’s Earth.

From an interesting post-Soviet cinema perspective see A. G. Rutkovsiy. “Zemlya

ot O. Kobylianskoi K A. Dovzhenko. Kinovecheskie Zapiski #23 (1994).

(Special Dovzhenko Earth Conference).

[225] For example, “The Boundary Line”. “I will be in

my death throes soon. See that you cover me with earth in the coffin, and do

not dress me. I want to be alone with the soil, like those who died on the

battlefield.” p. 156. Stefanyk has been translated into English. See Stefanyk,

Vasyl. The Stone Cross (trans. J. Wiznuk and C. Andrusyshen). Toronto:

McClelland and Stewart, 1971.

[226] Like Dovzhenko, Holovko would be one of this

period’s minority of Ukrainian writers to survive the purges. Weeds

exists in multiple versions. The post-Soviet Ukrainian uncensored version, comes

closest to Holovko’s original. The earlier English translation (Weeds

Kyiv: Dnipro, 1976) exists in socialist realist prose. Equally maudlin, the

early censored Ukrainian version (1927) is less censored than the English.

There is room for comparison with all of these versions with regards to Earth,

especially in light of its similar editing and Holovko’s early association with

Dovzhenko in the peasant writers’ association, Pluh. A comparison of

censoring practices between film/literature would be desirable as would a

taxonomy of these practices. Following Earth’s initial release, parallels in KINO’s

workers’ film reviews were made to Emile Zola’s naturalistic novel, La

Terre, and the classically oriented idyll, Longus’s Daphnis and Chloe. “Inshi

pro Zemlyu za Zemlyu”. Kino March 1930 (8), 80. Both of these novels had

been translated into Ukrainian and were enjoying a popularity, especially with

regards to the kinship between Longus and Kyiv’s then still permitted

neo-classical school. i.e. Rylsky, Zerov, Drai-Khmara, et al. Of these

resonances with Dovzhenko, ‘official angles’ have been pursued in Soviet

critique but there is room for further comparison, especially with regards to

Rylsky and the neo-classicists’ mode of detached Olympian posture as political

strategy. Rylsky has been translated into English. See Rylsky, Maksym. Selected

Poetry. trans. G. Evans. Kyiv: Dnipro, 1980. For Rylsky’s own take on

Dovzhenko see Ryl’s’kyi, Maksym. Pro Mystetstvo: Derzhavne Vydvo, 1962.

[229] Carynnyk, Marco. ed. and trans. Alexander

Dovzhenko: The Poet as Filmmaker. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1973., p. 274.

[230] Waly. “Soil: Russian Made Silent” Variety

October 29, 1930.

[231] i.e. Prague, Berlin, Hamburg, London and

Amsterdam.

[232] For a Russian translation of this article see Kinovedcheskie

Zapiski #23 (1994). Dovzhenko Conference Issue. ibid., p. 190. For a

reprint of the German original see Siegfried Kracauer. Kino. Essays,

Studien, Glossen zum Film. Frankfurt am Main: Herausgegebe von Karsten

Witte, 1974.

[233] Hall, Mordaunt. “the Screen: Earth”. New York

Times. October 21, 1930 (City Edition). 34:4.

[234] In Ukrainian, “Zemlya”, has connotations of

ground, land, country and nation. Andrusyshen notes. Zemlya: Earth, ground,

land, country, territory region; ridna zemlya, native land; Ukrainska zemlya,

Ukrainian territory; udaryty lykhom ob zemlyu, to drive away sorrow and abandon

oneself to joy; zemlyu topyty, to weep copiously, zemlyak, countryman. Ukrainian

English Dictionary Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995. p. 355.

[235] Carynnyk,

ibid., liii. About the nature and extent of these necessitated cuts

because of Bedny’s article, David Edelman concurs:

A particular pointed article. . .resulted in the

editing of several sequences including the scene where the tractor’s radiator

boils over and is cooled by the collective urine of the peasants, and another

depicting Vassily’s betrothed, naked and crazed with grief, mourning his death.

George Sadoul writes that the

original release time of Earth before censorship was 5,670 ft. (94 minutes at

16 frames/second, silent film speed). Sadoul, Georges. Histoire de l’art du cinéma. Paris:

Flammarion, 1949. After

censorship in the USSR, the film was cut down to 5,200 ft. (86 minutes). According

to Roman Savytsky, the prevalent supposedly ‘uncensored’ version of Earth

circulating in the 1950’s and 60’s in the republics ran 5,589 ft.[237] (93

minutes). For another

discussion of the different versions of Earth see Savytsky Roman.

“Pomiry Zemli O. Dovzhenka” Suchasnist Lypen/Serpen’ 1975 Chastyna 7-8

(175-76). pp. 106-112.

In North America, the 1950’-60’s

widely circulated and still present copies of the film from Soviet providers,

Audio Brandon and Artkino, reduced this to 4,860 ft. (81 minutes).

Reconstructed in the USSR during the Khrushchev thaw, the less censored Russian

thaw version to which Carynnyk refers began to circulate from Gosfilmfond

(Moscow) in North America in the 1970’s at 5580 ft. (93 minutes.) In the

nineties a North American video release version (KINO Red Silents) appeared,

which claimed to be copied from an earlier uncensored version of Earth but, in

actuality, drew on the Russian ‘Khrushchev thaw’ reconstruction. Projecting the speed at the incorrect 24 frames per second in its

video dubbing instead of 16 frames per second, the closer silent film speed,

the KINO video release version reduces Dovzhenko’s originally 94 minute film to

73 minutes. Because of Earth’s concern with stasis and motion, this

speeding up does violence to Dovzhenko’s rhythm. Dovzhenko’s original

conception of the film was predicated on a lyric static, painterly aesthetic.

In the original conception, little moves.

[239] This would explain party policy-centred attacks

that would appear in Pravda and Izvestia. While this event may

have occurred as Dovzhenko’s correspondence with Eisenstein begins shortly

after this time, it may be noted that Carynnyk dates Earth’s

post-production to December. (Carynnyk, Poet as Filmmaker, ibid.,

p. 274.) This would place Eisenstein out of the country. In his Eisenstein

study, David Bordwell dates Eisenstein leaving the Soviet Union for Europe in

August and not returning until after his Mexican debacle in the Spring of 1932. Prior to an early Earth screening in Venice by

the Italian communists, Deslaw comments: They cut the last moments in the

life of the grandfather, the return of the villager to his non-existent home

after picking up some earth (on his knees, the villager in this scene bends

towards the earth and, taking it in hand, raises it to his cheek, so in his

last moments to feel its flavor (smak) and to breathe in our black earth

(chornozem). They even didn’t leave other unique scenes with the sunflowers. .

. Deslaw continues “It’s possible that because of

Kremlin orders, copies of the film were ruined in the Soviet Union but beyond

these borders there exists two copies of Earth before the Venice cuts. In South

America there also exists another copy of Zvenyhora”. Deslaw, Evhan. “O

Dovzhenko i Stalin” Ukrainian Digest (no.6) 1961. p. 78-81.

[240] See Bordwell, David. The Cinema of Eisenstein.

Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993. p. 276.

[242] A 1955 New York Cinema 16 Club Circular

notes that the original negative of Earth no longer exists with prints

taken from an existing dupe negative with a subsequent loss in photographic

quality for which the film in its original form was praised. (Museum of Modern

Art Film Archives). Earth: Russia 1929-30. Cinema Sixteen Notes

The films had undergone a further three-pronged censorship translation and

transcription process. Before being sent to Moscow, the already

Ukrainian-censored VUFKU silent film was translated into Russian inter-title.

In Moscow, being sent to the West, the Russian inter-title version was edited

towards stronger propagandistic lines. Before being sent to various national

boards of censors in the West, the inter-titles were translated to English by

sympathetic western communists or fellow travellers whose first language was

not Russian (i.e. Shelley Hamilton, Jay Leyda, Herbert Marshall). Before wider

release, the National Board of Review and Catholic League of Decency requested

further emendation.

[243] Potamkin,

Harry Alan. “Soil Review, December 1930”. Reprinted in The Compound Cinema:

The Film Writings of Harry Alan Potamkin. New York: Teachers College Press,

1977. pp. 480-481.

[244] The figures come from V. Holubskyvych’s entry on

“Collectivization” in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Toronto: University

of Toronto Press, 1986. For a more detailed background on this period see

Conquest, Robert. The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the

Terror-Famine. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986. For a brief

essayistic overview see Mace, James “The Famine of 1932-33: A Watershed in the

History of Soviet Nationality Policy” in ed. Henry R. Huttenbach. Soviet

Nationality Policies: Ruling Ethnic Groups in the USSR. London: Mansell

Publishing Limited, 1990. For a more general illustrated overview of the

Ukrainian famine see Procyk, Oksana. Heretz, Leonid and Mace, James. Famine

in the Soviet Ukraine: 1932-33 (A Memorial Exhibition Widener Library,

Harvard University). Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986. For a later

published eyewitness account see Hryshko, Wasyl. The Ukrainian Holocaust of

1933. ed and trans. Marco Carynnyk. Toronto: Bariany Foundation, 1983. For

a collection of essays see Krawchenko, Bohdan and Serbyn, Roman. Famine in

Ukraine: 1932-33. Edmonton: CIUS Press, 1986.

[245] Conquest,

Ibid., 3-4.

[246]

Dovzhenko, Alexander. Uncensored Autobiography, 1994., ed. Nebesio,

Bohdan. The Cinema of Alexander Dovzhenko. Journal of Ukrainian

Studies. Volume 19, No. 1., p. 21. There is a different version of this

paragraph in a single page essay “Pro Zemlyu” (On Earth) dated 1930 in

Dovzhenko’s 1964 Complete works. See Tvory: 4, ibid., p.111.

[247] In repeated letters to Eisenstein, Dovzhenko put

this as his desire to see Hollywood, New York, San Francisco and collaborate

with Chaplin. See Tvory: 5, ibid., “Letters to Sergei Eisenstein

and I.O. Solokyansky from Berlin and London” (1930) pp. 325-330.

[248] i.e. Rotha, Grierson, Leyda, Marshall, Ivens,

Montagu, Barbusse, Aragon, Malraux, Mousinnac, Bryher, Bakshy, Potamkin.

[249] On the early U.S. reception of Soviet Silent

Films in America see Vlada Petric’s unpublished NYU Ph.D. dissertation Soviet

Revolutionary Films in America (1926-35). New York University, 1973.

Relevant for further investigation with regards to Dovzhenko are Chap. 3 &

4. “Social Background and Political Climate of the Period” pp. 41-60.

“Political Reaction of American Media Towards Soviet Silent Films” pp. 60-89,

“Ideological Influence of Soviet Revolutionary Cinema on Leftist Film

Theoreticians” pp. 206-240”. And Petric’s Appendixes (V & VI) of early

English books and articles published on Soviet Silent Film through 1936.

[250] Petric,

ibid., pp. 61-62.

[251] Petric,

ibid. pp. 68.

[252] i.e. New Masses, Daily Worker, Film

Front, Nation, New Theatre, Workers Theatre, Film

Front, Workers Film and Photo League, etc.

[253] Magosci, Paul Robert. A History of Ukraine.

Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996. p. 563.

[254] i.e. Amkino.

[255] i.e. Potamkin, Workers’ Film and Photo League,

New York.

[256] In his first KINO diary note (September

19, 1933) which would find its way into the chapter his Soviet cinema history,

Jay Leyda references the Ukrainian famine in an aside with regards to VGIK, the

Soviet film school, then housed in a former Tsarist Russian imperial

restaurant:

On the way out (and GIK

is way out, in a building once the Yar restaurant, huge place, probably the

closest thing to a Tsarist roadhouse) S. told me that Lusha (the cook) had come

to them in the farm famine six months ago, when the small farmers and kulaks

refused to reap their crops. S described Lusha’s swollen belly and sunken face

then in a way that brought famine into the tram. Leyda, Jay. “Witnessed Years” Kino:

A History of the Russian and Soviet Film. Princeton: Princeton University

Press, 1983. p. 301.

Walter Duranty’s early New

York Times review regarding Earth “Moscow in Furor over Kulak Movie”

would cloud debates for the West rather than placing Earth into context.

With regard to his Ukrainian famine reporting, Malcolm Muggeridge would call

Duranty ‘the greatest liar of any journalist I have met in fifty years of

journalism’, Conquest, ibid., p. 320. For a study of the western

resonance of this debacle see Carynnyk, Marco, Luciuk, Lubomyr and Kordan

Bohdan. The Foreign Office and the Famine: British Documents on Ukraine and

the Great Famine of 1932-33. Kingston: Limestone Press, 1988. For Duranty

in particular see pp. xxix-xxxi. lvinn., 36, 39, 202-205, 209-210, 217, 455

n.29, 456 n.108.

[257] Early English translated famine memoir,

emigré, foreign observer and published eyewitness accounts: Ammende, Ewalde. Human

Life in Russia Introd. Lord Dickinson. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1936

(Reprinted Cleveland, 1984). Kravchenko, Victor. I Chose Freedom: The

Personal and Political Life of a Soviet Official. New York: Charles

Scribner, 1946. Solovey, D. The Golgotha of Ukraine: Eyewitness Accounts of

the Famine in Ukraine. New York: 1953. Woropay, Olexa. The Ninth Circle: