Zvenyhora

(1928): Ethnographic Modernism

Introduction |Zvenyhora (1928) | Arsenal (1929) | Earth (1930) | Conclusions

Filmography | Earth Chronology | Bibliographies | Contact

|

Zvenyhora has remained my most

interesting picture. I made it in one breath - a hundred days. Unusually

complicated in structure, eclectic in form, the film gave me, a self-taught

production worker, the fortuitous opportunity of trying myself out in every

genre. It was a catalogue of all my creative abilities. (Dovzhenko, Autobiography, 1939)[6]

|

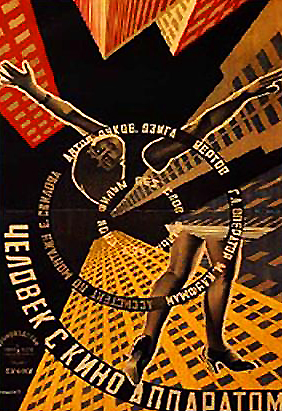

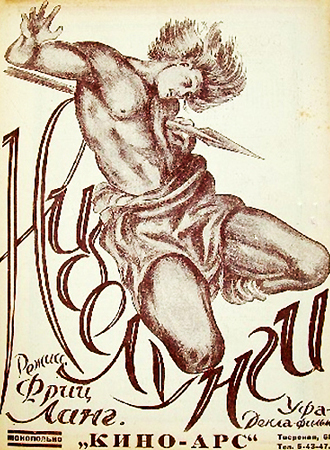

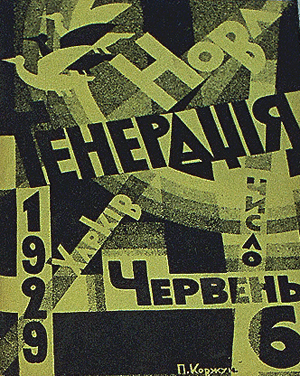

Zvenyhora Sternberg Brothers Poster, 1927 |

At the time of its release in 1928, Zvenyhora was the first and would be the most luxuriant of Alexander Dovzhenko’s silent trilogy (Arsenal, 1929, Earth, 1930). After its April 13, 1928 Kyiv premičre, a flurry of debate on the film was published in Ukraine’s leading cultural, political and literary journals and newspapers.[7] Kyiv’s VUFKU studios compiled a book of essays[8] on the film’s impact by a few leading lights of the intelligentsia.

The expressionist poet and critic, Yakiv Savchenko’s, reaction to the film was not untypical: “At the least, Zvenyhora heralds a larger creative step for our film culture, it stands in a new and authoritative place in its aesthetic development”.[9] Writing in the critical journal, Zhyttia i Revolutsiia (Life and Revolution), Mykola Bazhan, editor of the Ukrainian film journal, Kino, commented, “Well, up till now we haven’t been accustomed to speak seriously about our cinema”[10].

Zvenyhora (1928), Full Movie, 91 minutes

Zvenyhora is a difficult and gnomic film. This has become a commonplace in western film circles. Where mention of the film occurs, the film is more often quoted than discussed; where discussed, more in confusion than toward understanding. In 1961, the drama critic of New York’s Herald Tribune, commented, “Zvenigora has much that will be obscure to anyone not familiar with Ukrainian legendry, and its rather naive acceptance of Communist folklore makes part of what is clear rather absurd”.[11] Less connected with Moscow and Meyerhold than with the Surrealism of Breton, Dada of Grosz, comedy of Chaplin and Sennett and French avant-garde film of Clair, Zvenyhora’s dialogue was also with international modernist aeshetic currents in regional variant.

|

|

|||

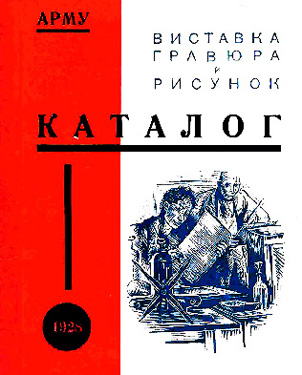

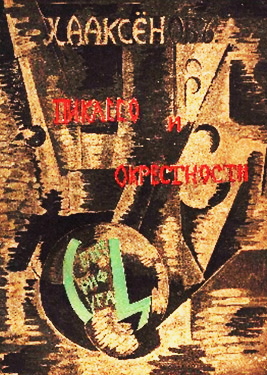

| 1928 Artists Catalog for ARMU, Association of Revolutionary Artists of Ukraine, Constructivist Design | Alexander Exter's Cubist Bookcover for "Picasso and His Contemporaries" 1917 |

The western Soviet film historians who comment on Dovzhenko at any length[12] all recount an early screening at the Moscow Art Theatre. From this event, Zvenyhora is given status and Dovzhenko is confirmed a new ‘auteur’.[13] What is worth noting from the commentaries is the astonishment that the film provoked for the other masters of ‘Soviet Cinema’s Golden Age of Experimentation’ - Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin.[14]

Soviet film historian and early student at Moscow’s VGIK film school, Jay Leyda, writes about Eisenstein’s pronouncements of a March 1928 screening:

‘I beg you, please come’, the VUFKU representative in Moscow repeated over and over on the telephone to Eisenstein, “I beg you - come and see this film they’ve sent us. No one here can understand it, it’s called Zvenigora. . .”

We enter the Hall of Mirrors in the Hermitage Gardens, where the Moscow Art Theatre began their work on the Sea Gull, and where this incomprehensible film is to be projected for us. Here a young Ukrainian director is to receive his baptism of fire. “Is it or isn’t it good? Help us decide,” the VUFKU man implores. . .

I sit down beside Pudovkin. We both had just come into fashion - and weren’t yet venerable. . .in the crush we meet the director - his name is Alexander Dovzhenko.

Onto the three screens of the Hall of Mirrors - the true one and the two side ones that reflect it - Zvenigora leaps!

Mama! What goes on here!. . .

Already I reflect sadly that the film must eventually end and that I’ll have to find something intelligent to say. For us ‘experts’ this is also an exam - But with the tripled image emphasizing the fantasy, the film races on. . .

As the film goes on it pleases me more and more. I’m delighted by the personal manner of its thought, by its astonishing mixture of reality with a profoundly national poetic imagination. Quite modern and mythological at the same time. Humorous and heroic. Something Gogol about it. . .

Pudovkin and I now have a wonderful task: to answer the questioning eyes of the auditorium with a joyful welcome - our new colleague.[15]

Even for a contemporary audience with a knowledge of Ukraine’s history, Zvenyhora was a difficult film. Shortly after the film’s initial furore, Dovzhenko was prompted to reflect on the confusion the film caused for contemporary audiences:

Do I hear the objection that some among our audience didn’t understand our film. What of it? Am I supposed to stand at the front of the theatre before every screening and say: “Dear audience member, when there is something you don’t immediately understand, don’t jump to the conclusion that what is before you is unintelligible or ill-conceived.[16]

Ranging over a millennium of Ukrainian history, Zvenyhora progresses in a disjunctive temporal manner among the October Revolution, real and mythologized events from Ukrainian history, folkloric stories and Slavic pagan tradition. Not unlike the episodic structure of Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) or Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), Zvenyhora (1928) follows an episodic structure that has analogues with Russian Cubo-futurists works and Velimir Khlebnikov’s supersagas[17].

|

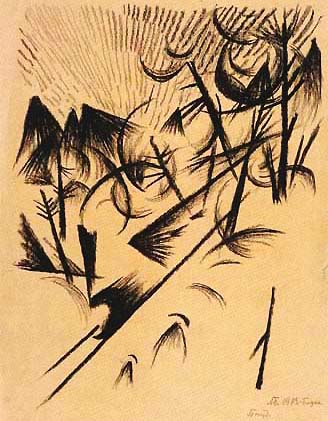

Its imagery is also close to Kino editor, Mykola Bazhan’s “Budivli” (“The Buildings”, 1928)[18] Moving from epoch to epoch, Zvenyhora mixes styles and genres. Zvenyhora’s episodic synthesis of different forms resonates with the period’s search for new structures. | ||

| Mykola Bazhan's Buildings (1928) |

Vance Kepley summarizes the film as a series of disparate sequences. A Soviet critique divides Zvenyhora into thirteen episodic tableaux[19]. The 1983 Kyiv published edition of Dovzhenko’s complete works divides Zvenyhora’s scenario into six parts (the final scenario parts veering completely from the actual print).[20] Staying closer to the North American print, following is a seven part schematic:

Episode 1: A Ukrainian ‘chumak’ (salt-trader) grandfather takes up with a group of ‘haidamaky’ (cossacks) on horseback and together, they progress to Zvenyhora’s mountains (lit., ‘The Ringing Mountains’). There, they look for treasure, fight Poles who hide in trees and are frustrated by a devilish monk. Emerging from a hole in the ground with rosary and lantern, this figure proceeds to haunt the film’s further sections.

Episode 2: Spying a group of traditionally dressed young maidens preparing for the spring pagan fertility ritual of Ivan Kupalo, the grandfather continues in his intermittent nightmare about the monk while presiding over two grandsons, the dreamer and nationalist, Pavlo, and the industrious Bolshevik worker and soldier, Tymish.

Episode 3: Tymish fights in World War I and then joins the Bolshevik forces while Pavlo and the Grandfather dig into Ukraine’s mountain for Zvenyhora’s treasure.

Episode 4: The grandfather relates the ancient legend of the pre-Slavic tribes and the maiden, Roxana, to credulous Pavlo. In a symbolic expressionist sequence, Roxana and her people are subjugated by Turkish and Viking invaders.

Episode 5: Painting a black horse white, Pavlo joins the Ukrainian nationalist forces to fight his brother Tymish’s Red Army troops in the civil war.

Episode 6: After the war Pavlo raises money in Western Europe (Prague, Paris) by a peculiar avant-garde Dadaist/constructivist suicide performance to finance another treasure hunt. The new Bolshevik student, Tymish, educates himself with young workers.

Episode 7: As a train approaches Zvenyhora, the nationalist brother, Pavlo urges the grandfather to grenade and sabotage train tracks. The old man is prevented from doing so by the young Bolsheviks led by Tymish. Ultimately, the nationalist brother, commits suicide. Taken into the train with the Bolshevik brother, the grandfather joins the progress towards a new communist utopia.

Zvenyhora begins with a group of ‘haidamaky’ on horseback in the

countryside. In 1841 Ukraine’s poet laureate, Taras Shevchenko, had written an epic

poem devoted to these haidamaky bands. Closer to Dovzhenko’s period, Ukrainian

theatre director, Les Kurbas, and his Berezil Theatre[21] had

restaged this romantic poem in an experimental modernist variant (1922).

|

Dovzhenko suggests the narrative’s oneiric, surrealistic nature by emphasising the riders’ motion through the use of slow motion. Popularizing surrealism through Europe, the French poet, André Breton, had published the Surrealist Manifesto (1924) a few years earlier. In Zvenyhora’s year of production, he had led the Surrealists into communism to encourage that project ‘of recreating the universe to which Lautreamont and Lenin had dedicated themselves”[22]. | |

| La Revolution Surrealiste (1924) |

During the pre-revolutionary period there was a vibrant cross-cultural travel and dialogue among the artists of the Ukrainian avant-garde[23]. Paris was the centre of the art world.

|

|

||

Alexandra Exter City, 1915 (Paris/Kyiv) |

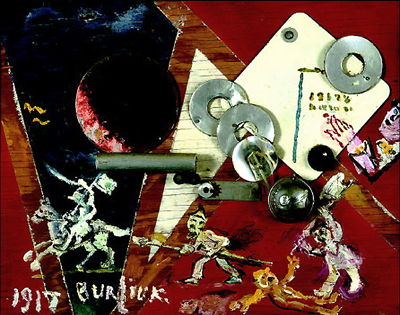

David Burliuk, Revolution, 1917 |

In the sea of changes precipitated by World War I and Revolution, Ukraine had briefly emerged as a nation (1917-19). Cultural renaissance and euphoria filled the air. After the Bolsheviks had overrun Ukraine during the civil war, they displayed hostility toward the Ukrainian language. At this time Dovzhenko was a member of the Soviet diplomatic corps. In the spring of 1922 he became an art student in Berlin returning to Ukraine only after the creation of the republic (1922). During the Bolshevik period regarded as ‘Ukrainization’(1923-33) or ‘Korinizatsiia’ (lit. putting down roots) Dovzhenko returned, the masterpieces of his silent trilogy, (Zvenyhora, 1928; Arsenal, 1929; Earth, 1930), produced out of this liberal crest of Bolshevik policy to bring the Ukrainian populace onside[24].

|

During this period Dovzhenko lived in a building on Pushkin Avenue with the leader of the Ukrainian futurists, poet and critic, Mykhail Semenko, novelist and screenwriter, Yuri Yanovsky, and Kino journal editor, critic and poet, Mykola Bazhan[25]. At this time he was an active member of VAPLITE (Vilna akademiia proletarskoi literature - Free Academy of Proletarian Literature. Emigré literary historian, Ivan Koshelivets, points out that VAPLITE’s meetings were first held at Kharkiv’s film studios, VUFKU and more than a few members had ties with the cinema. Composed of the young cultural intelligentsia, VAPLITE published poetry, prose, art and cultural criticism. | |

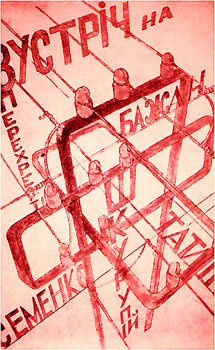

| Bookcover for Poetry Anthology Meeting at the Crossroads, Mykhailo Semenko, Mykola Bazhan and Vladimir Tatlin |

Dovzhenko’s literary and artistic associations in this period prior to the trilogy were with a group that would become the leading cultural figures of the twentieth century Ukrainian cultural and political avant-garde. Later, Ukraine’s great poet of the 1920’s, Pavlo Tychyna, would write introductions to Dovzhenko’s published books. Leader of the Kyiv neo-classicists, Maxim Rylsky, would become the editor of Dovzhenko’s various editions of complete works. The leading lights of the cultural intelligentsia would produce articles, books, painting, sculpture, poetry or novels devoted to Dovzhenko.[26]

As one of the named members of VAPLITE, Dovzhenko was an integral part of a larger intellectual circle. Influenced by the ideas of Mykola Khvylovy (1893-1933), these artists and writers were caught up in national emancipation and revolution. Accused of later being an anti-party and nationalist organization, VAPLITE was to be short-lived. Stalin himself would write Khvylovy and VAPLITE’s denunciation.[27] Necessarily distancing himself from the group, Dovzhenko would later write an apologia for his association with VAPLITE, Khvylovy, and its members (two of whom, Maik Johansen and Yurtyk, (pseud. Yuri Tiutiunnyk), wrote the screenplay for Zvenyhora).

Dovzhenko’s first and longest polemic statement was published in VAPLITE. This essay was not on cinema but visual art. At this time, Dovzhenko was an illustrator for Hart ) and the Kharkhiv art journal, Nove Mystetstvo (New Art, 1925-28)[28].

|

In

“On the Problems of the Visual Arts”[29],

Dovzhenko’s orientation was away from ‘heroic realism’ and Russian

‘Peredvizhniki’ (Wanderers) which were advocated by the conservative

Association of Artists of Red Ukraine, ARKhH (Asotsiiatsiia Khudozhnykiv

Chervonoi Ukrainy) and towards the nascent flourishing of the avant-garde.

|

Dovzhenko’s position was in alignment with ARMU (Association of Revolutionary Art of Ukraine). In his first polemic article Dovzhenko distances himself from the Moscow inspired ARKhH’s orientation towards the nineteenth century Russian social realist painters and later realist art advocated by Soviet officialdom. Dovzhenko advocates the alignment the Ukrainian art ‘front’ with Western Europe and modernism embodied by the umbrella group, ARMU | |

ARKhH and ARMU Comparison, V. Sedliar, 1920's |

The period of Zvenyhora’s production was one of international modernism. Dadaists, Surrealists, Futurists and other European movements were known and emulated around the globe.

|

|

|

||

Vasyl Yermilov. Journal Cover for "Avant Garde" (1929), Kyiv |

Maria Syniakova's Merry-Go-Round (1916), Kyiv, Primitivism |

Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Hair, 1915, Bronze, Kyiv |

In his contemporary novel Macunaima (1928), the Brazilian modernist, Mário de Andradé, would work in a similar manner to Dovzhenko in his cutting and mixing of genre, colonial critique and relationship with more dominant modernisms. In the year of Zvenyhora’s production, the German cultural critic, Walter Benjamin, would write in an essay on Surrealism,

Intellectual currents can generate a sufficient head of water for the critic to install his power station on them. The necessary gradient, in the case of Surrealism, is produced by the difference in intellectual level between France and Germany[30].

Dovzhenko had already spent more than a few years abroad as a diplomatic attaché in Warsaw and subsequently as a student of the plastic arts under the tutelage of George Grosz in Berlin. About this earlier developmental period and Grosz’s influence, Alfred Krautz notes,

This Berlin artist of nearly the same age as Dovzhenko was coining a very personal drawing style by which he was revealing in a merciless and hard-hitting way the social evils of his time, the philistinism of the bourgeoisie, the moral decay of the ruling class and an attack on German militarism. His studio was a center of anti-imperialist forces. Professor Wieland Herze-felde, the brother of John Heartfield, vividly recalls encounters with Dovzhenko in the studio of George Grosz at this time. The stylistic influence of Grosz resonate in the poignant satirical depictions of reactionaries and philistines in Dovzhenko’s silent films.[31]

|

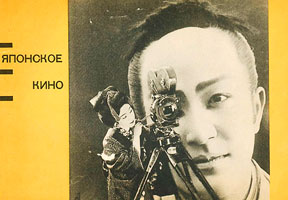

From diary notes, Soviet film historian, Jay Leyda, confirms about the filmmaking climate and interest in European modernist film aesthetics in Ukraine at this time, “When Leon Moussinac visited Kharkov, he had difficulty asking questions (of the filmmakers), for most of the time was taken by the questions asked of him, chiefly about the films of Clair, Cavalcanti, Epstein, Dulac, Man Ray, and Leger.”[32] Much of the European, American and even Japanese filmmaking avant-garde (i.e. Mizoguchi, Ozu, Kinugasa, Page of Madness, 1926) was known to the Ukrainian filmmaking community. | |||

Early Kyiv Studios (VUFKU) Exhibition of Japanese Cinema (1928),Photomontage El Lissitzky |

||||

| The cosmopolitan Ukrainian language film journal Kino (Kharkiv, 1925, Kyiv, 1926-32), devoted thematic issues to German, Japanese, French, American and then vibrant Ukrainian Yiddish cinemas. Isaac Babel, Sholom Aleichem, Alexander Granovsky, Marc Chagall and Natan Altman all had ties to Kyiv’s VUFKU studios. Keeping tabs on the European and American filmmaking communities, Kino had correspondents in the various European but also Asian and American filmmaking centres[33]. |  |

|||

VUFKU Studios Emblem. Design by Dovhzenko's set designer V. Krychevsky |

Prior to Zvenyhora’s production, Kino had profiled the French

filmmaking avant-garde, focusing on Clair, his early films and the surrealist

and dadaist-inspired, Paris Qui Dort (1923), Entre Acte (1924)

and Le Fantôme Du Moulin Rouge, (1924).[34]

Dovzhenko’s slow motion filming in Zvenyhora’s opening recalls a similar

sequence from Clair’s Dadaist succčs de scandâle, Entre Acte (shot

in1924, theatrically released in 1926).

|

In Entre Acte, the Dadaist

nose-thumb at conventional bourgeois representations of reality takes the form

of older, well-dressed bourgeoisie behind a hearse drawn by a camel. Clair

gradually increases the pace until he eventually reaches a normal camera speed.

Cane-carrying mourners move in slow motion strides[35].

Interestingly, Zvenyhora’s cossacks are analoguous with Clair’s critique of a

historical remnant from an older era, the bourgeoisie. This will be emphasized

in Zvenyhora through constant highlighting of the cossacks’ horses and

contrast and visual rhyme with the train.

Up to the revolution, Ukraine did not exist as a nation. It had been integrated into the Russian Empire. Laws prohibiting the use of a Ukrainian language in schools or in literature were in effect. The cultural debates occurring during this period ranged across the plastic arts. As that seventh art closely tied to a double-edged sword of economics and aesthetics, filmmaking was, in many senses, centre-stage. In his famous injunction to the Bolsheviks, Lenin put this as, “Of all the arts, for us, the most important is the cinema”.[36]

In Zvenyhora’s opening images, centre frame within a group of ‘haidamaky’ is a bandura-carrying cossack, a minstrel, or ‘kobzar’

|

The association is with the historical ‘kobzars’, repositories of tradition and the source of folk, historical and religious information. Contemporaneous with Dovzhenko, Vladimir Tatlin would similarly articulate the kobza’s connotations through a modernist Dadaist mixed-media woodblock collage in his yellow and blue relief, “Bandura” (1914-1915). Here, the kobza’s contemporary analogue, the bandura, would be reduced to rough hewn yellow woodblocks against a blue set of boards. Together, background and instrument, form the colors of the then outlawed, Ukrainian flag.[37] | |

Bandura, Vladimir Tatlin, 1914-15, Yellow and Blue Relief |

||

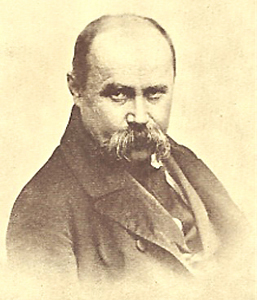

To the Ukrainian audience, the ‘kobzar’ in this opening sequence is a reference to Ukraine’s major poet, Taras Shevchenko, (1814-1861) and his book of poetry named for these bardic singers - Kobzar (1840).

| The visual evocation of

both the centrally placed ‘kobzar’ and ‘haidamaky’ band in Zvenyhora is

a reference to the Oedipal father of Ukrainian letters, Taras Shevchenko. During this same period, Dovzhenko’s colleague and founder of Ukrainian futurism, the poet, critic and ‘enfant terrible’ of Ukrainian belles lettres, Mykhail Semenko[38], had incited a literary scandal. About Shevchenko’s Kobzar, the young Semenko had provoked a cause célèbre by his republication of futurist poems bearing and profaning the same name of Shevchenko’s Kobzar (Semenko, 1924). |

|

|

Taras Shevchenko Photograph circa 1860 |

Made explicit in a letter by himself and screenwriter and novelist, Yuri

Yanovsky, to VAPLITE, Dovzhenko was aware of Semenko’s gesture. He

wrote, “We love Mysha Semenko, author of Kobzar No. 2, but he shouldn’t

be signing our names to his manifestos without telling us”[39].

Earlier, Semenko had made repeated Dadaist attacks on the atrophied aesthetics

he felt Shevchenko’s Kobzar had degenerated among Ukraine’s peasant

masses.

In light of competing views on the status of Shevchenko’s Kobzar,

it is no surprise that on Zvenyhora’s premiere, its images would

provoke, divergent and often antithetical critical reception.

| Dovzhenko evokes Shevchenko through the blind cossack minstrel epic singer. He burlesques cossacks through a Chaplinesque mock-heroic Keystone cops-like routine. The question is not so much veneration or disparagement, but the ambivalent expression of both gestures. A good analogue to what Dovzhenko is doing would be Marcel Duchamp’s “L.H.O.O.Q” (1917). Here, Duchamp paints a mustache on the Mona Lisa. Through its desacralization, the profaning of high art takes on modernist veneration. | ||

|

||

| L.H.O.O.Q, Marcel Duchamp, 1917 |

In long shot and slow motion Zvenyhora’s central character, the old

grandfather, is presented against a grain field and dirt road. He is at once an

unlikely figure for a film’s central character or hero. Far from the heroes of

Stalin’s monumental or Stakhanovite social realism, the grandfather is dressed

in traditional white ‘chumak’ (salt-trader) outfit and pulls a horse and cart.

|

About these characters Dovzhenko would later write:

They were hardly individualized. They were embodiments of ideas and ideologies. I was still operating in the Zvenyhora manner, using class categories, not individuals. . .

(and then a little later as to confound this)

Who are my heroes? Father, Mother, Grandfather and myself.[40] |

|

| Ancient Grandfather, Mykola Nadems'kyi |

||

Described in his autobiographical Ukrainian literary classic of the Thaw, Zacharovana Desna (The Enchanted Desna), the ageless grandfather at Zvenyhora’s beginning presents a portrait of Dovzhenko’s real life grandfather but also an embodiment of the peasant class. Similar to Pudovkin’s film on Gorky’s novel[41], Mother (1926), Zvenyhora presents, albeit briefly, the awakening to consciousness of the Ukrainian peasant class.

| In the grandfather’s walk and

sometimes comic clown-like antics there is also some of Chaplin’s lone prospector in search of treasures in Gold Rush (1925). Here, the treasures are hidden in Zvenyhora. Like Gogol’s subversively sly village beekeeper narrator from his Ukrainian stories, the peasant grandfather will be able to get away with narrating stories not officially ‘allowed’ because of his peasant naiveté and comic antics. |

|

|||

Cinema and Photo, Constructivist Cover with Charlie Chaplin, 1925 |

When we first encounter him, the aged grandfather is presented as a

‘chumak’, one of the wagon drivers who carried grains, salt and fish across the

steppe. Drawn from historical fact, the portrait is of Dovzhenko’s own

grandfather. As presented in Zacharovana Desna, the picture is also a

part of a mythopoetic notion symbolizing an older way of life. About this

wooden cart way of life, Dovzhenko writes in The Enchanted Desna:

I liked to fall asleep on the hay-wagon, and then half waken as it halted in the yard and somebody carried me indoors. I liked the creaking of wheels under heavy loads at reaping times(15). . .Setting off to mow was always a long business. Sometimes the sun would rise before we made a move. There was plenty of noise and running about. Mother found fault with this and that; and now, when she saw me, her voice rose above all the din.

“You’re not taking the boy?. . .Leave him at home, the mosquitoes’ll eat him alive!”. . .

I lay in the middle of the cart, with the backs of Granddad, Dad and the mowers rising around me. I was being taken to the kingdom of grass, rivers and mysterious lakes. Our cart was made of wood only, for Granddad and Great-granddad had been oxcart drivers (Chumaky) in their day and such men do not like steel, they say it draws lightning.[42]

In Zvenyhora, the ‘chumaks’ and their way of life is replaced by railroads and a train. This displacement from wooden cart to the train will be alluded to in Zvenyhora’s final scene. Against the approach of a moving railway train, the grandfather brandishes a grenade. He is then taken aboard by the young Bolsheviks and given a cup of tea. The ‘chumak’ class will not be replaced so much as taken on board to become ‘fellow travellers’ in their own country.

Zvenyhora’s Treasures

It was a country where dumplings simply rolled themselves into the mouth.

(Pushkin on “Little Russia”)[43]

Zvenyhora was by no means the first Ukrainian film to use folkloric, literary or historic antecedent or source. For this we need only look at the list of that era’s silents: Historical Drama, Bohdan Khmelnytsky (Drankov, 1910); Comic Operetta: Zaporozhets Za Dunaiem (Drankov, 1910), Natalka Poltavka (Sadovsky, 1911); Historical Drama: Zaporozhian Sich (Sakhdenko, 1912); or even Literary Biography, The Life of Taras Shevchenko(Chardynyn, 1926). What was singular about Dovzhenko’s use of folklore, history and literary antecedent was his contemporary historo-political savvy and appropriation into a unique modernist mythopoetic. To unpack Dovzhenko’s poetic suggestions as to what exactly Zvenyhora’s treasures entail[44], perhaps it is wise to preface this section by summarizing the folktale from which Dovzhenko’s film takes its name.

The Zvenyhora ‘kazka’ (oral folktale) begins with a poor disenfranchised

peasant wondering how his family is to survive the upcoming winter. Straying

into Zvenyhora’s mountains, the peasant spies a cave where he falls asleep.

Over the hoots of owls and howling wolves the peasant has strange dreams.

Awakening, he finds the cave full of vaults, gold coins, jewellery and

treasure. Stuffing his pockets, the

peasant begins to leave, whereupon the treasure’s guardian, a horrible looking

man, pronounces, “I shed innocent blood for this treasure. Now there is a curse

on me and my riches. The earth will not accept my body. God will not accept my

soul.” In some variants, this figure is Oleksa Dovbush, a historical

Robin-Hood. As the leader of the ‘haidamaky’, Dovbush was said to have taken

from the rich and given to the poor. In some versions, Dovbush also killed many

of his conquests keeping more than his share of riches. In the Zvenyhora

‘kazka’ the peasant empties his pockets with the exception of two gold coins

and puts the rest back into the barrels. Arriving home soon and making good use

of the coins, the peasant begins to prosper. His neighbours begin to talk and

the peasant recalls how he had gotten lost in the woods and stumbled on

Dovbush’s treasure. Taunting the poor peasant, the other villagers provoke him,

saying that if he had really witnessed Dovbush's treasure he would not have

been left without a full barrel. Setting off again, the peasant finds the

barrels only to recoil in horror, finding them full of vipers and snakes. The

story ends with the wind howling “Take only what you need.”[45]

Looking now at Zvenyhora’s visualization, Dovzhenko’s poor peasant meets

a figure analogous to the legend’s Robin Hood-type character, not in

Zvenyhora’s caves but in the film’s opening scene.

|

In Dovzhenko’s version, the Dovbush figure takes on the identity of an evil monk, a Mabuse Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) or Nosferatu (1922) from the annals of German expressionist cinematography current to the period. | |

Zvenyhora's Monk, note the double superimposition |

||

Rather than having the peasant grandfather meet Dovbush as a dead personage, recalcitrant for his sins, Dovzhenko figures Dovbush as alive and the leader of a ‘haidamak’ band, placing the peasant grandfather in the middle of one of his historic raids on Polish landowners. The ambiguity as to whether the grandfather is going back in history or whether he is dreaming this set of events is left open. The grandfather’s quest in Zvenyhora is economic - a quest for riches. The mystery as to who owns the riches, where to dig to find them and where they lie will be riddled with ambiguity. The ‘haidamak’ bands are presented as both heroic and marauders. In Dovzhenko’s folktale variant, Zvenyhora’s riches are never found or as soon as they are in hand, as the grandfather and ‘haidamak’s’ brief holding of the chalice and jewels suggest, they disappear or turn into worthless objects.

In the use of folktale and allegory, Dovzhenko presents an economic enigma. Through the backdrop of early twentieth century Ukraine, the grandfather quest for Zvenyhora’s riches, and the question as to who owns them and whom to fight against, will be explored. Historically at this time, the Ukrainian populace was overwhelmingly a peasant populace.

|

The contemporaneously mythologized, Eisensteinian disenfranchised urban proletariat that supposedly precipitated the revolution did not hold for the Ukrainian steppe. On the eve of the Russian Revolution, Ukraine was considered “the breadbasket of Europe”. Its populace was predominantly rural, and, for the most part, ‘un’ or ‘pre’-industrialized.[46] Judging by the film journal, Kino, rather than proletariat and the city, the problems and debates revolved around the question of peasants and village [47]. For the Ukrainian populace, early Soviet visualizations of an urbanized Russian proletariat (i.e. Strike, 1925; End of St. Petersburg, 1927; Bed and Sofa, 1927) were having a difficult reception. | |

Poster for Eisenstein's October (1928) |

Looking back at Dovzhenko’s Zvenyhora folktale variant, it is not hard to read his conceit as economic and at its base, Marxist. During this time, Soviet Ukraine was in the process of releasing itself from the memories of a cycle of wars, colonial exploitation and anarchy - and embarking on a period as a newly created republic of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. For many Ukrainian intellectuals at this time, it was not a far connection between Soviet Ukraine’s newly created vassalage and an earlier historic relationship.

Digging, archaeologically excavating or looking downward to buried strata for treasure, is a central trope through Zvenyhora . The grandfather excavates unofficial or previously imperially prohibited folklore, literatures, anthropologies and histories. But what is the excavation’s character, towards what purpose and why the official prohibition? In a discussion of psychoanalysis and ethnology in The Order of Things, Michel Foucault speculates on the social unconscious that ethnology presents. Championing ethnology as a discipline able to dissect the naturalized ‘order of things’ in state power or neo-imperial orders, Foucault calls ethnology ‘the knowledge we have of peoples without histories’. His observations are well applicable to the historical, economic, cultural and social renaissance and caesura occurring in Ukraine and Zvenyhora’s subsequent ‘irritation’ and threat to the new order’s establishment.

Foucault writes:

Psychoanalysis and ethnology occupy a privileged position in our knowledge not because they have established the foundations of their positivity better than any other human science, and at last accomplished the old attempt to be truly scientific; but rather because, on the confines of all the branches of knowledge investigating man, they form an undoubted and inexhaustible treasure-hoard of experiences and concepts, and above all a perceptual principle of dissatisfaction, of calling into question of criticism and contestation of what may seem, in other respects, to be established. Now, there is a reason for this that concerns the object they respectively give to one another, but concerns even more the position they occupy and the function they perform within the general space of the episteme. . .[48]

| What is so disturbing to the ‘new’ official culture about the old grandfather’s digging is that the peasant is unearthing or excavating strata of folklore, mythology, tradition and even ‘objects’ that allow a national identity’s visualization. In the ‘caesuras and dividing lines’ that these narratives refract, they allowed critique of what would otherwise be an uncontested, progressive or naturalized teleology of a neo-imperial mythology. In Zvenyhora, the grandfather brings to the surface histories of peoples who imperially, economically and politically were not given the ‘official’ right to be called peoples. |  |

|

Zvenyhora's Ancient Grandfather |

In microcosm, this excavatory trope visualizes the ‘caesura’ brought to the surface by the events of the world war, the revolution and the fall of empire. The caesura opens the question, ‘What are the consequences and implications of being without ‘official’ rights to language, culture or history and what these seemingly naturally allow?’

Foucault continues:

Just as psychoanalysis situates itself in the dimension of the unconscious (of that critical animation which disturbs from within the entire domain of the sciences of man), so ethnology situates itself in the dimension of historicity (of that perpetual oscillation which is the reason why the human sciences are always being contested, from without, by their own history). It is no doubt difficult to maintain that ethnology has a fundamental relation with historicity since it is traditionally the knowledge we have of peoples without histories; in any case, it studies (both by systematic choice and because of the lack of documents) the structural invariables of cultures rather than the succession of events. . .[49]

Zvenyhora provides a visual analogue for this study of ‘structural invariables’ of an officially prohibited culture. Contemporaneously, a larger fissure and subsequent ‘neo-imperial Bolshevik’ suture was historically occurring. It could be seen in Mykhailo Hrushevsky’s historical investigations[50], the economic analysis of Volubuiev[51], the Ukrainian Cultural Renaissance’s irritating of orthodox ideology[52], or the equally ethnological and suppressed Jewish Renaissance[53]. All of these ‘fissures’ posed a threat to the ‘mythos of union’ and ‘unity’ of the new imperium. They foregrounded ‘difference’ not similitude. The similitude that they did foreground was the wrong one, suggesting a continuity between the Romanov imperium and its rearticulation by Bolshevik culture through a ‘politically correct’ Marxist rhetoric.

| In later orthodox Soviet film histories Zvenyhora became marginalized - a footnote. It presented a threat to official communist histories. Even for something like an ‘avant-garde’ film canon (i.e. Soviet heroic age, Eisenstein, Pudovkin), Zvenyhora and its representative grouping crossed an ‘allowed’ horizon of possibility. To many intellectuals and emigrés of the time, ‘Soviet Union’ would become the new catchphrase for Russian chauvinism and a cloaked imperialism masquerading under a politically correct trope - socialist utopia. The republic’s voices that would not fit the Soviet general line would subsequently be repressed and then erased. |  |

||

Zvenyhora's Stalin-like Officer |

|

In Zvenyhora. the officer’s comments to the grandfather are: “You grandfather, are a real engineer. But digging is forbidden here. Chase the old man away. Set up a guard.” The threat that the grandfather’s ethnographic digging and historical participation perform are not so much in unearthing evidence as denaturalizing foundational ground of an accepted, uncontested past and ‘order of things’ to make possible a critique of a seemingly politically correct ‘epistemological’ order. | |

| Zvenyhora's Grandfather with Officer |

Again, Foucault is useful:

Ethnology, like psychoanalysis, questions not man himself, as he appears in the human sciences, but the region that makes possible knowledge about man in general. . .The privilege of ethnology and psychoanalysis, the reason for their profound kinship and symmetry, must not be sought, therefore, in some common concern to pierce the profound enigma, the most secret part of human nature; in fact, what illuminates the space of their discourse is much more the historical a priori of all the sciences of man - those great caesuras, furrows, and dividing lines which traced man’s outline in the Western episteme and made him a possible area of knowledge. It was quite inevitable then, that they should both be sciences of the unconscious: not because they reach down to what is below consciousness in man, but because they are directed towards that which, outside man, makes it possible to know, with a positive knowledge that which is given to or eludes his consciousness.[54]

From a Marxist perspective, what becomes troubling about Zvenyhora’s economic conceit, is its early ambivalence towards ideas of ‘proletarian’ revolution and ‘Union of Republics’. The film’s visual tropes engender spectatorial observations towards ideas of economic vassalage. Ruled by some form of imperialism for the past two hundred years, Zvenyhora’s eternal peasant is not a member of the urban proletariat but like the majority of Ukraine’s population at this time, a rural peasant. Theoretically, Marxism was supposed to first take hold in more technologically advanced nations. It had taken hold in one of the least technologically advanced with a large disenfranchised rural and peasant population.

|

Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Vertov and Schub would narrativize problems of the ‘proletariat’. For Ukraine, the images and subsequent historical myths would not hold. As has been commented by emigré dissident historians (i.e. Koshelivets, Berest), the grouping of Soviet masters (i.e. Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Dovzhenko) has also to do with a political construct. A central tenet of Soviet revolutionary Marxism was the dicta that a society’s economic relationships provided a key to understanding that society’s nature and character. What would be the consequences of asking this question: If the treasures of Zvenyhora (Ukraine), the largest foreign and former colony of the Russian Empire, were being exploited and disappearing from the peasant class’s hands, was the newly centralized SSR then no less guilty of the sins of imperialism than its predecessors | |

Poster for Vertov's Man with a Movie Camera (1929) |

Dovzhenko visualizes this question through the trope of digging. In an intricate sequence, the montage intercuts among inter-titles reading “The Revolution is in Danger”. Miners throw iron-ore; men scythe grain; the old grandfather digs; a mechanical hammer hits a hot steel bar showing the construction of Soviet socialist utopia’s construction. To pull the revolution out of danger, various aspects of society work together. In the later “Roxanna Sequence”, the central image of war upon war and conquest after conquest will be a ritualized, balletic and symbolic chopping of heads by consequent lineage of historical victor upon victor. Ironically, this repetitive head chopping motion is visually rhymed with the Soviet hammer flattening steel. The earlier rhythmic motion was meant to suggest the positive ‘flattening of steel’ to build a socialist utopia. Through an uncomfortable parallelism, Dovzhenko forces suggestions that saving the revolution means economically disenfranchising or cutting off a political body’s head. Pulling the revolution out of danger means a death and decapitation, but whose? What type of new structure is to be built?

|

Following this sequence, Dovzhenko visualizes a monumental horrific tower, a half-constructed Babel. Lines cross lines, but to what purpose ? Except for a fat officer showing up on a white horse proclaiming, ‘My hand creates miracles’, this remains a mystery. The sequence is followed by a series of explosions crushing a set of bridges.

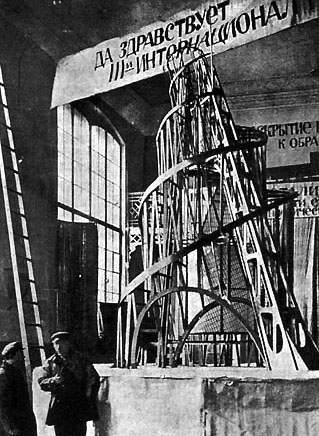

In an earlier sequence, Dovzhenko had shown the lyricism of the peasants working in a pastoral harmony. Here, the camera rises in an industrial elevator-type structure. Line against line anarchically cross. A monolith is being constructed. As to its organization, purpose, or even place in Zvenyhora’s schema, it is difficult to discern. Not with any sense of geometric harmony but pronounced chaos, the structure for the socialist utopia that Dovzhenko envisions is closer to a creaky tower of Babel. Similar to Italian modernist, Giorgio De Chirico’s, industrial landscapes with giant naked girder structures and crane hooks, Zvenyhora’s notable absence is man. The structure that Dovzhenko envisions is in antithetical relationship to the utopian aspiration of Vladimir Tatlin’s revolutionary and ordered harmonics in his unbuilt “Monument to the Third Internationale”(1920)[55].

|

Or, if not antithetical, then parodied. Giving an example of these types of metaphorical Soviet architectural structures, Igor Golomstock comments:

The dominant in the structure of the future Moscow was to be the Palace of the Soviets. The largest church in Moscow - the Church of Christ the Saviour near the Kremlin - had been pulled down shortly before, and it was on this site that the stepped tower, 415 metres high and crowned by a 100-metre statue of Lenin, was to be erected. Taller than the recently constructed Empire State Building, it was to house the supreme organs of Soviet power and the apartments of the Leader. . .Sceptics pointed out that in bad weather Lenin’s head and outstretched hand would be hidden behind the clouds, but this failed to diminish the great enthusiasm. . .Both the architecture as a whole and the symbolism of the decor were intended to express the power of the country of victorious socialism.[56]

Similar to Dovzhenko’s unfinished behemoth in Zvenyhora, the Palace of the Soviets was never finished. As utopian possibility, this shining red path is overtly presented in Zvenyhora. Complexly, this representation is undercut through necessary secondary signs. More often than not, it is parodied or placed into an iconic situation in which irony and dystopia cannot help but suggest themselves.

Aleksander Rodchenko, Superstructural Abstraction (Photo, 1928)

In Zvenyhora’s road building sequence at a construction site, horse-driven carts carry soil. A group of workers struggle with hammers building a road. The others struggle with shovels. Suspending a board in the air and using the workers’ efforts to walk an overbearing path, a man easily walks a tight-rope over them. The visual parody is of a worker-base, neo-colonial superstructure. Previously, the horses carried the cossacks and the grandfather majestically, nodding in agreement with their master’s aspirations. Here, the horses are crippled by heavy loads and obese mustached officials. In an allusian to Social Revolutionary writer Ivan Franko’s utopian social revolutionary aspirations in his poem “Pavers of the Way”, Dovzhenko has the inter-title pronounce, “Roads are not built by unclean hands.”[57]

Dovzhenko’s allusion to Ukraine as an economic satellite of a veiled Russian imperialism calling itself ‘International Communism’ called to question what would be historically relegated to the unspeakable - the communist claim that Soviet power and ‘union’ offered a viable alternative to imperialism. For the republics’ intelligentsia of this period, one of the questions in 1928 was whether the republics at this stage of the revolution would become mere economic satellites? Was a cloaked Russian imperialism working under the rubric of a politically correct neo-colonial oppression under the name of communism?

‘October’ and the fall of empire had different connotations for the republics’ intelligentsia and populace. After hundreds of years of being dominated by Polish, Austrian, Hapsburg or Russian imperial empires, Ukraine had experienced a year of freedom. When the economist Mykhailo Volubuiev published his comparative study in which it was pointed out that, because of its statistically increased neo-colonial burden, Ukraine’s position was worse now under the USSR than in the tsarist empire, it was not looked on kindly by the Bolsheviks.[58]

Zvenyhora was later denounced and marginalized by historic sources. These prescriptions would be followed as source material for film historians in the West. To glance at an early ‘English’ language piece of elegant constructivist critique entitled Soviet Film History, the Soviet hagiographer as film historian comments on Zvenyhora:

Around this work on national themes there develops a sharp class struggle, a political struggle. The bourgeois nationalists of all hues and shades try to make use of the national themes for their own ends. Under the mask of nationalist romanticism and idealised feudalism, there was concealed the advocacy of the restoration of capitalist and landlord rule in the Ukraine. In this struggle against the reactionary nationalistic elements the best masters of the Ukrainian Soviet cinema have emerged and developed, notably such a great master as Alexander Dovzhenko. Only after the heavy burden of the legacy of reactionary moods disguised in romantic forms has been disposed of, was the Ukrainian cinema able to grow into a progressive art, into a realist art that is “national in form and socialist in content.” . .In Zvenyhora one may recognize already the future Dovzhenko, the author of such outstanding works as The Arsenal, Earth, Ivan, although in this first big production he still pays tribute to false romanticism, subsequently eschewed by him, as a survival of bourgeois nationalism.[59]

There is a binary of perspective here that encourages an elision. These types of conjectures would marshall Zvenyhora and the cultural groupings it represented to a historical absence. Soviet pronouncement would be embraced through an acceptance by an early generation of western film historians and fellow travellers[60], who would take up a de-historicized Marxism in their differently oriented political struggles.

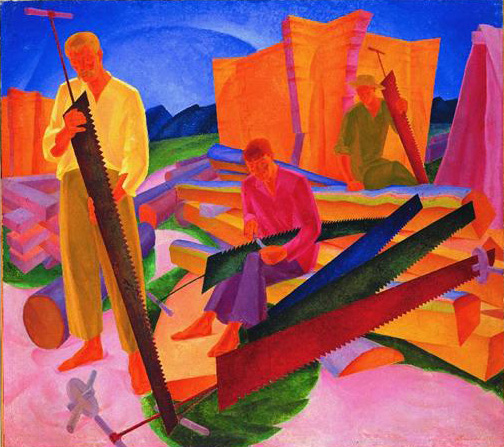

Alexander Bohomazov's Sawyer's (1929)

In what is considered ‘the history of Russian and Soviet Film’, Jay Leyda, would write about Zvenyhora, “It bears little relation to Dovzhenko’s basic film-ideas, and in later years he omitted it from the list of his work.”[61] Leyda is mistaken. His pronouncements establish citational genealogies and are followed by most future western Soviet film historians. More interested in setting up a dialectic with capitalism than examining historical fissure, this accumulation and re-circulation of data would contribute to the muting of an archive.

To unpack the implications of Arrosev’s seemingly ‘sensible’ comments on Zvenyhora, the binary that is forwarded is that ‘the nationalist romanticism of Zvenyhora conceals an advocacy of the restoration of capitalist and landlord rule in Ukraine’. The binary is between antithetical ideas of ‘Capitalism’ with that of ‘Communism’; it is a binary that makes structural sense but puts the republics’ material historical realities to pasture.

Writing about ‘other’ unrealized paths for the revolution within the Ukrainian context, James Mace comments:

Ukrainian national Communism was in a sense the successor of a particularly national brand of socialism that had evolved long before the revolution of 1917. Such an ideology, first systematically expressed by Mykhailo Drahomanov in the 1870’s and later cast in a Marxist framework, arose in response to the particular situation of the Ukrainian nation. The propertied classes in pre-revolutionary Ukraine were overwhelmingly non-Ukrainian, while the Ukrainians were almost wholly a nation of peasants who were not yet free of the vestiges of serfdom and who lived under a government that promulgated laws against printing materials in the Ukrainian language. The Ukrainian peasantry thus provided a natural constituency for those who could articulate both their national and social grievances. The Ukrainian national intelligentsia created an amalgam of nationalism and socialism capable of expressing the aspirations of the nation’s rural majority, enjoyed widespread popular support, and was able to establish an independent Ukrainian Peoples’ Republic. Although Ukrainians were unable to maintain their political independence, they could effectively block the establishment of any regime that did not take into their aspirations for national liberation.[62]

Prior to this period, Dovzhenko was a supporter of what is now a little spoken of other path for the Revolution, National or Ukrainian Communism, articulated by the Ukrainian Borotbist Party[63]. Against a cloaked Russian imperialism, the Borotbisty’s agenda was for a third path or independent communist state. In opposition to an early Russian Bolshevik ‘central committee’, the Ukrainian Borotbisty, with which Dovzhenko associated, saw little need for the nascent socialist revolutionary Ukraine to assume a role of an economic vassal state, or Zvenyhora-type natural resource base The ambivalence in Zvenyhora’s images and association with the Ukrainian national communists is in evidence in Dovzhenko’s 1939 autobiography. In order to be reaccepted into the CP(B)U[64] or Internationale, Dovzhenko plays apologist with acrobatic justification to answer for his rank and file[65] Borotbist Ukrainian communist association. He writes,

Early in 1920 I joined the Borotbist (Ukrainian Communist) party. This action, wrong and unnecessary as it was, happened in the following way. I had very much wanted to join the Communist Party of Bolsheviks of Ukraine but considered myself unworthy of crossing its threshold and so joined the Borotbists, as if entering the preparatory class in a gymnasium, which the Borotbist party, of course, never was. The very thought of such a comparison seems absurd now. In a few weeks the Borotbist party joined ranks with the CP(B)U, and in this manner, I became a member of the CP(B)U.[66]

The list of Ukrainian Borotbists, their association with the Ukrainian literary and cultural intelligentsia and most, if not all, of the party’s leading theoreticians and associations and ties with Dovzhenko is numerous. Suffice to say, most of Dovzhenko’s Borotbist colleagues would be coopted into the CP(B)U, silenced or imprisoned. The mention of the existence of an independent Ukrainian Communist Party would be made anathema. By 1931, while many of his lesser-known Borotbist colleagues were systematically in the Gulag or liquidated, Dovzhenko, internationally well-known, was prevented by Stalin from making further films in his country. Granted a Moscow internal exile, he was later made to rewrite and denounce his personal history and association by his own hand.

Dovzhenko’s was forced to write his autobiography as a condition of application for party reacceptance. He mentions Zvenyhora in this ‘autobiography’ in 1939,

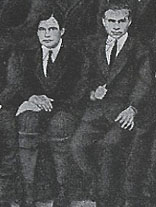

| “The script (of Zvenyhora) was written by the writer Johansen and the not unknown Yurtyk (Tiutiunnyk). There was a lot of devilry and blatant nationalism in the script, and so I rewrote about ninety percent of it. The authors then demonstratively removed their names from the credits. This was the beginning of my parting of ways with the Kharkiv writers.[67] |  |

|||

Dovzhenko seated next to Maik Johansen (longstockings) circa 1928, VAPLITE Membership Photo (Detail) |

Dovzhenko selects his facts (substitutes Kharkiv writers for the then Stalin

denounced VAPLITE) and confesses to past ‘mistakes’ in order to be readmitted

by the Communist Party.[68]

Ironically, this version of events was taken at face value by most western

Soviet film historians[69].

Along with the majority of destroyed, censored or suppressed material from Ukraine’s renaissance of the 20’s (poetry, plays, prose, polemics, film and fine art), Zvenyhora would also be proclaimed by Stalin as an example of ‘bourgeoisie nationalism’. Subsequently, it would never make it to the West until long past Dovzhenko and Stalin’s death.[71] The visual evidence in Zvenyhora could not easily be erased. Later, it became marginalized by subsequent generations of Soviet critics and tacit agreement in the West.

Sacré Du Printemps

Zvenyhora’s second major sequence presents the ancient grandfather participating in the Slavic celebration of ancient pagan origins, marking the end of summer solstice and beginning of the harvest - Midsummer’s Eve, or in the Slavic variant, the Festival of Ivan Kupalo. Well-known in the West is this festival’s slightly earlier Parisian Ballet production, Sacré du Printemps.

|

||

Dancers from Diagheliv's Production of Stravinsky and Nijinsky's Sacré du Printemps (1913) |

Dovzhenko’s evocation of the Kupalo ritual is similar to Diagheliv's earlier succès du scândale of composer Igor Stravinsky and choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky Sacré du Printemps (1913). Both find roots in the ethnographic but also the oneiric, archaic and uniquely modern. Figures in this sequence of Zvenyhora and in the later Roksana sequence also find striking parallels with Nicholas Roerich's Sacré du Printemps costume designs . More than documenting ethnography, the presentation of these rituals dialogue with an earlier awakening and ‘rebirth’ peculiar to the period. Dovzhenko visualizes the Kupalo ritual’s details alluding to folklore, the ‘khorovod’ or ancient form of folk dance, but also winking at the 1860’s historical ethnographic revival as evident in the writings of Gogol, Kostamorov, Kobylianska, Kotsiubinsky and early Ukrainian ethnographers.

|

At a riverbank’s edge, young women gather in traditional embroidered garb. In

the hope that doing so will improve their chances of marriage, other maidens

run barefoot in bedewed fields. Taking a wreath off her head and flinging it

onto the water’s surface, one young woman in a boat watches her wreath float

down stream. The portraiture refers to Kupalos’ eve folk traditions of young

women adorning their hair with freshly-cut flower garlands and releasing the

garlands later to the fates to see who whom they were destined to marry.

In an early ethnographic work, W.R.S Ralston comments:

In the evening, after the ‘Khorovod’ games are over, the maidens go to a stream and throw their wreaths in, singing all the while:

I will go to the river Danube,

I will stand on the steep bank

I will throw my wreath on the waters:

I will go afar off and see,

Whether sinks or sinks not

My wreath in the water.

If the wreath swims steadily, without running ashore, its late wearer will marry happily and live long; if it circles around one spot, there is reason to fear some misfortune, a broken engagement or an unrequited love; and its sinking is a very evil omen, foreboding that he or she who wore it will either die soon, or at least go down to the grave unmarried.[72]

Dovzhenko has the ancient grandfather move carefully through rushes. As a young maiden watches in horror, the old man picks up the wreath.

Sacré Du Printemps Costumes, still image, circa 1929

The Political Unconscious of Set Design

Beside the cottage cherry trees are swinging

Above the cherries May-bugs winging,

Ploughmen with their ploughs are homeward heading

And lassies as they pass are singing.

(Shevchenko,“The Cottage”, 1847)[73]

Automobiles drag around the village

Sheep and spokes fly here and there

The only cherry trees swinging are in your head.

(Semenko, “The Village”, 1929)[74]

Immediately after Zvenyhora’s brief lyrical sequence in which the audience’s sympathies have been engendered towards the value of the surrealist and oneiric, the grandfather’s two grandsons and other main figures in Zvenyhora are presented. Pavlo, the Ukrainian nationalist dreamer, lies on a cot in a traditionally embroidered shirt and blowing bubbles out of a straw. The image is jarring. The previous Kupalo sequence had presented liberatory dream variants and encouraged a positive association with ‘the dream’. The second brother, Tymish, is visualized repairing a shoe. He is the subtle parody of the proletarian ideal.

This is the first and last time the two brothers will appear together in the same scene in Zvenyhora. They are the progeny of the same grandfather but a split has occurred. Progressively building through the narrative, Dovzhenko will complicate and confuse the two brothers through abrupt and seemingly ‘misplaced’ narrative editing. Rather than weaving an unconnected tapestry of visual sequences, Dovzhenko builds a complexity of argument and association that is achieved through montage. At times, the brothers become indistinguishable, at other times, a spectrum of opposition.

The violent intra-psychic division and figuring of brother against brother is a central endemic theme to this period of Ukrainian cultural history. The figuring of conflict among family members has antecedent in other representational media (literature, film, theatre, critique, the visual arts). One need only look at the motifs of this period’s surviving plays, poetry or visual arts. Burliuk, Boychuk or Syniakova’s paintings[75]; Khvylovy’s polemics; the early poetry of Semenko, Tychyna, Shkurupii, Bazhan; the work of theatre director, Les Kurbas, or the playwright Mykola Kulish’s Ukrainian tetralogy[76] all provide analogues of this theme.

At the time of national rebirth, cultural renaissance and communist revolution,

the intellectuals of Dovzhenko’s generation came to political and social

consciousness - aspirations at first mutually complementary, but then

increasingly exclusive. The widening degree of polarity and growing sense of

solitude between these forces forms a subsequently suppressed stratum of

Dovzhenko’s aesthetic.

In this early scene, all three figures occupy the same house, the traditionally

decorated “Ukrainska Khata” or village home that figures on a number of

levels in Zvenyhora.

|

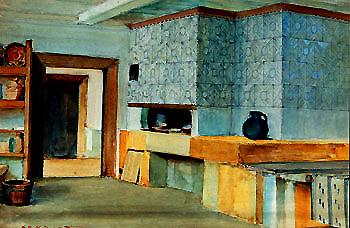

Prominent in the single room’s interior design are the traditional wall draperies (Kilims), embroidered table coverings (Rushnyky), wall decoration and calligraphy (Rospys), prominent icons, ceramics and a ‘pich’, or stove, on top of which the old grandfather sleeps. It is not a proletarian or urban apartment such as the room presented in Abram Room’s Bed and Sofa (Tretia Meschanskaia, 1927), or even earlier three-walled stage proscenium-like spaces of Russian pre-revolutionary master, Yevgenii Bauer’s, bedroom melodrama Silent Witness (1914). His space is closer to the rural masses. | |

| Vasyl Krychevsky, Watercolor for a traditional village home | ||

Dovzhenko repeats this same gesture and trope later in written stories, (i.e.‘Khata’) and diaries:[77]

Poor little cottage, what haven’t you seen in this world, who hasn’t robbed you, beat you up, shot at you? What people haven’t spent the night? It’s hard to understand how you stand at all, how you look out of your dark windows on God’s earth. What has happened, what thoughts and songs are no longer sung, and how they weep. . .[78]

In Zvenyhora, this allegorical space’s disruption is figured through set design. An awkward background map of the various ‘fronts’ in Ukraine and the White Army’s ill-placed portrait of one of the Romanovs is placed into the room’s interior. The home’s interior structure is not so much taken from realism’s tenets or naturalism and peasant way of life, but from a designed politico-cultural stance[79].

An important Ukrainian journal that Dovzhenko could have read at teacher’s college was the Kyiv published (1909-14) Ukrainska Khata, Ukrainian Home. Mykola Sribliansky (pseudonym Mykyta Shapoval), one of the journal’s editors, summarizes the journal’s dialogue with the Ukrainian variant of modernism:

Modernism in Ukrainian criticism refers to that current of literary-social thought that appeared in Ukrainska Khata (Ukrainian House). To a certain degree this is true. It was Modernism but not in the sense of ‘newness’, because khatianstvo (‘housism’ or ‘domesticity’ with the complex association referring to the journal and currents it inspired) never had anything to do with decadence in literature, nor with Modernism in religion. Our Modernism was a reappraisal of the Ukrainian movement, and our relationship to Ukrainian history, a reappraisal of our relationship to our revolutionary contemporaries, who created the revolution of 1905, a reappraisal of our liberation ideology and the search for a new ideology of liberation.[80]

In presenting the “Ukrainska Khata”, or home, in Zvenyhora, Dovzhenko articulates a dilemma and debate that preoccupied the writers of the early modernist journal, Ukrainska Khata. What characterizes Ukrainian modernism? Elucidating the resistive context, George Luckyj provides the historical background:

Concerning the repeated attempts by the tsarist administration to hinder, suppress and ban the growth and use of the Ukrainian language, literatureand culture, the arrest of Shevchenko in 1847 with the explicit order that he should be prevented from writing or painting, the notorious pronouncement of the tsarist minister of the interior, Valuev, in 1863 that “there never has been, is not, and never can be a separate Little Russian language,”(Ukrainian) and the consequent ban on practically all Ukrainian books except belles-lettres, this all culminated in the 1876 prohibition of all Ukrainian publications, except historical documents and censored belles-lettres, and the simultaneous ban on the importation of all Ukrainian books from abroad.[81]

Living within the historic shadow of the draconian cultural measures of the Ems and Valuev decrees, Dovzhenko’s visualization harkens to Ukrainian modernism’s search for an ideology of liberation. As alluded to earlier with the journal, Ukrainska Khata, this ‘avant-garde’ gesture was achieved through a resistive focus on the folk’s domestic space. Dovzhenko visualizes the domestic space as a form of transgression. A good analogue for this is North American ‘feminist’ or ‘gender’ conceptualism of the 1970’s and early 1980’s where the ‘domestic space of the kitchen’ and ‘traditional women’s handicrafts’ are reappropriated and foregrounded.[82]

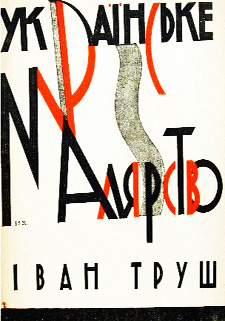

|

In an early review of Zvenyhora, the expressionist poet, Mykola Bazhan, highlighted the political importance of Dovzhenko’s set design and collaboration with artist and professor, Vasyl H. Krychevsky.[83] Krychevsky was mentioned in a series of articles for, among other sources, the journal, Zhyttia i Revolutssia[84], the film journal, Kino[85], and the earliest Ukrainian book[86] devoted to the significance of Zvenyhora. In the first book published on Ukrainian cinema, issued in a bilingual edition of Ukrainian and French, along with Vertov, the actress, Julia Solntseva, and Dovzhenko, prominently featured among VUFKU’s luminaries would be one of the studio’s set designers - Vasyl Krychevsky.[87] Preceding Zvenyhora’s Ukrainian release, VUFKU’s KINO had published two profiles on Krychevsky. The first focused on this cultural figure working in the cinema, profiled in tandem with Dziga Vertov, and Dovzhenko’s future cinematographer, Danylo Demutsky. A little later, Kino would devote a piece to “Fine Artists and the Cinema[88]”, focusing on Krychevsky and a discussion of folklore, cinema and aesthetics. | |

| Vasyl H. Krychevsky, Zvenyhora's Set Designer | ||

Prior to Zvenyhora, Krychevsky had worked as set designer on a now mostly lost and Bolshevik CP(B)U destroyed grouping of Ukrainian silents made after the Revolution: Taras Shevchenko (Chardynyn, 1925) based on the life of the poet and starring Ambrose Buchma in the role of Shevchenko (Buchma would later be given the interesting casting choice of the role of the gassed soldier in the opening scene of Dovzhenko’s Arsenal, 1929); the children’s film, Young Taras, (Chardynyn, 1926); Taras Triasylo (Chardynyn, 1926), a historical drama based on the seventeenth century haidamak uprisings, starring again Buchma as the cossack’s leader and again finding echo in both Zvenyhora and Arsenal; Two Days (Staboviy, 1926); Borislaw is Laughing (Ron, 1927) based on the earlier social revolutionary writer, Ivan Franko’s, novel.[89]

More than isolated masterpieces different from the general line of ‘Soviet

Golden Age’ cinema (ie. Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Vertov, Schub), Dovzhenko’s

trilogy presented discourse unacceptable in later definitions of Soviet Heroic

Age Avant-Garde film. The published evidence of these ‘other’ silents

(1923-1932) comes from contemporary cultural journals[90] and

(‘samvydanny’) emigré cinema workers’ memoirs. Ironically, these memoirs and

early denunciations of these films[91] are

the remaining evidence of these films’ subject matter.

After the 1917 Revolution, Vasyl Krychevsky[92],

was, along with Dovzhenko and many of the Ukrainian cultural workers, a

participant in a later suppressed national rebirth.

|

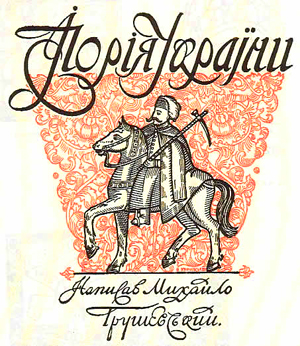

Art historian, architect, painter, graphic artist, set designer, master of applied and decorative art, Krychevsky was a recognized figure by the time he came to work for Dovzhenko. He had designed state buildings and monuments based on folk architecture, was singularly recognized for founding modern Ukrainian book design and had re-articulated traditional folk ornamentation and motifs in a variety of media. At the behest of Ukraine’s president, the historian, M. Hrushevsky and during the brief year of independence (1917), Krychevsky had designed the state emblems, seals of the UNR (Ukrainian National Republic) and currency. In 1906 Krychevsky also provided illustrations for Hrushevsky’s History of Ukraine, considered one of the sources for Ukrainian history and only allowed to be cited in Ukraine after the Soviet Union’s fall. | |

| Vasyl Krychevsky's Bookcover for Hrushevsky's History of Ukraine, 1912 | ||

Prior to his role as VUFKU set designer, Krychevsky had played a role in

traditional Ukrainian handicraft techniques revival. Many of these historically

(re)newed artifacts find their way into Zvenyhora. An adherent to Ruskin

and William Morris’s view on the relation of arts and crafts to everyday life,

Krychevsky served as an instructor during the national rebirth conducting

traditional cloth and kilim weaving workshops, ceramics schools and furniture

building. He had also amassed one of the more important repositories of

traditional folk art (over 600 objects) in Ukraine, housed at President

Mykhailo Hrushevsky’s Kyiv residence. During the Bolshevik offensive,

Hrushevsky’s important manuscript collection was burned and Krychevsky’s

artifact collection, destroyed.

In an early article about Krychevsky’s aesthetics in a political context, Mykola Bazhan distances Krychevsky’s use of ethnography from a minstrel charade or colorful curiosity. Bazhan places Krychevsky’s ‘arts and crafts’ rearticulation into a dialectic with previous colonial portrayals of Ukrainian culture by Drankov and Khanzhonkov who saw ‘little’ Russians as colorful primitives interested only in the quartet of ‘horilka’ (whiskey), ‘hopak’ (dance), ‘Shevchenko’ and ‘sharovary’ (baggy trousers).[93] About Krychevsky’s Zvenyhora role, Jay Leyda would comment, “Professor Krychevsky, the artistic supervisor, had a nervous breakdown” during filming.[94] In contrast, Kino editor, Mykola Bazhan, would emphasize that Krychevsky was not so much interested in ethnography, as rearticulating ethnography to bring out a submerged political valence.

Vasyl Krychevsky's Constructivist Design for the Series "Ukrainian Painting" (1928-31)

Roksana

|

||

Ancient Maiden, Drawing for Sacré du Printemps, 1913, Nicholas Roerich |

The outlines of Zvenyhora’s Roksana section is taken from Ukrainian history. Born Nastia Lisovska in Rohatyn, Galicia (1505), Roksana is captured by Crimean Tartars (1520) and sold to the Ottoman sultan, Suleyman I of Canuni. Roksana captivates the Turk’s imagination and the sultan makes her his first wife. Veering into legend, Roksana becomes a heraldic figure, betraying Turkish husband and freeing the Sultan’s captured cossacks. Dovzhenko’s Roksana does not follow orthodox retelling. It does follow in the epic lament and ‘oral tradition’ of the ‘Dumy’ genre: captives versus foreign or colonial oppressors, in this case, Ottoman Turks. The theme of a foreign conqueror is not unique to Roksana but follows a historical line from the Ukrainian epic tales of historical lament, the ‘dumy’.

|

Sitting on the grass next to his nationalist grandson, the ancient grandfather, bard-like, recounts a story. Intertitles read: “Listen to a secret. A great treasure is hidden here in Zvenyhora[95] - in ancient time when strangers walked our lands they were led by military men”. Following these intertitles, the narrative flashes back to the historical legend of Roksana, a Ukrainian woman captured by Crimean Tartars and sold into the Turkish sultan’s harem. The subject of an opera by D. Sichysky (1908), a play by H. Yakymovych (1869) and a book by O. Nazaruk (1930), Roksana has a history in popular Ukrainian mythology preceding and following Zvenyhora.[96] | |

| Zvenyhora's ancient grandfather | ||

In Zvenyhora, Roksana is conflated with temporally disparate historical narratives linked by similarity of theme: the Duma of Maria Bohuslavska; an earlier arrival of Polovtsians and Varangians to Kyivan-Rus (circa 870 A.D.); the subsequent historical controversy surrounding Kyivan-Rus’s origins (18-20th centuries) and an interweaving with later historical periods involving cossacks and the ‘haidamaky’ raids.

| Kept alive in ethnographic, folkloric, ‘narodny dumy’ (literal. thoughts of the people), oral or bardic-contexts, these narratives have in common contested histories or submerged social critique prohibitive in earlier imperial contexts (i.e. belle-lettres, history books; Valuev and Ems Decrees). The aesthetic is ethnographically surrealist. In a Bretonian sense, it is surrealist in presenting a dream-like, utopian chronicle of events. Not so much national consciousness as national ‘unconscious’, the orally told narrative advances a history of a geographical set of boundaries which are denied status as a country. In the previously discussed Foucauldian sense, the narrative is ethnographic, recounting the asynchronous history of a land without an ‘officially’ sanctioned history, “structural invariables of a culture rather than the succession of events”[97]. Through the peasant grandfather’s narrative, a submerged or unconscious social history is presented. |  |

|||

Polovtsian Prince Igor, Anatoly Petrytsky, 1926 |

Through Zvenyhora’s presentation of competing histories - one imperial, official, hegemonic, colonial and written; the other ethnographic, marginalized, oral and submerged - the concern is not so much with presenting histories as it is to elucidate borders or formal structures of culturo-social unconscious. Through Zvenyhora’s ethnological presentation, Dovzhenko denaturalizes or ‘makes visible’ colonial borders of power/knowledge. In a two-shot, a cossack-attired child shoots a toy-arrow against a towering empirical warrior. In the humorously impotent gesture, it is not difficult to witness the tiny cossack’s allegoric nature and relationship between a nascent nation state and succession of imperial force.[98]

The central gruesome image of the Roksana sequence is chopping of heads. In its multiplicity and repetivity, the ritualized beheading suggests history’s movement through bloodshed and war. Through at times triple-layered exposure and ritualized battle, one man symbolically lowers a sword, the other lowers his head. History progresses with the victor chopping the vanquished’s head.

The Roxana sequence also complexly dialogues with ‘the glyph’ and long stone tablets.

Detail from Scythian Battlescene, Gold , 430-390 BC, Dnepr Region, Ukraine

As early historical markers of chronicles of war,.[99]

Dovzhenko composes elements in a moving rectangular visual panorama that is

suggestive of narratively sequenced scenes on ancient stone tablets (i.e.

paying tributes, slaves with oxen and carts, battles, dragon ships, battles).

By using an arsenal and range of Melies-type film trickery - double and triple

exposure, layering of events, slow motion, intricate camera masks and an

operatic German expressionistic emblematic style - Dovzhenko layers historic

myth and legend. By having a camera mask block out top and bottom so that the

viewing area takes on a long rectangular composition, Dovzhenko highlights the

hieroglyphic nature of his aesthetic. The representation is an example of

ancient ‘visual narrative in time’. Dating back to the ancient Assyrian-carved

battle chronicle tablets, the meta-commentary is on history’s construction and

recording. Prefiguring and paving the way towards the cinema, the allusion is

to ancient victors’ battle chronicle tablets.[100]

| In terms of aesthetic style, there is a debt to German expressionism, Wagnerian opera and Dada. In form and content, Dovzhenko alludes to Wagner’s ring cycle, specifically, Fritz Lang’s recent epics based on Wagner, Niebelungen Saga (1924) Siegfried’s Death (1924) and Kriemhild’s Revenge (1924). In the Roksana sequence, the bumbling aged grandfather casts himself as the dramatic hero. Far from Siegfried’s position, the grandfather mimics the gestures of the king of dwarves, Mime. In Lang’s Niebelungen, Siegfried is inflected as Germanic, heroic and fearless. Dying from a spear wound where a leaf previously alit, this is the only vulnerable place on his Teuton’s body. In Zvenyhora, Roksana takes not Siegfried’s analogue but, ironically, the knife-thrower against Teutonic Siegfried evocation. Parodically, Roksana’s knife refuses to dent the antagonist. With Roksana waving her arms, standing on the Viking boat sinking into the sea, there is the sense not of the heroic or sublime but of a mock-operatic travesty of Lang’s proto-Fascist solemnity.[101] |  |

||

| Poster from Kino-Arkhh for Lang's Niebelungen Saga (1924). Dovzhenko will parody and pay homage in the Roksana sequence. |

Ukrainian Constructivist Dada

Colonial syllogism: No one can escape from destiny. No one can escape from dada. Only dada. . .

(Tristan Tzara, Seven Dada Manifestos, 1924)[102].

After the civil war sequence, both brothers find themselves in different countries and with different agendas. Pictured at a workers’ technical school, Tymish, the converted Bolshevik brother, writes on a blackboard. He tries to formula out Zvenyhora’s secrets through engineering’s quadratics. An inter-title tells about the nationalist brother, Pavlo, “Meanwhile, the refugee cossack walks in Prague, sweeping the streets with baggy trousers”.

|

|

|||

Zvenyhora's Worker Brother |

Zvenyhora's Nationalist Brother |

For the contemporary audience, the sequence paints a Rorsach test, determinant of and reflecting back the spectator’s point of view. The later historical critique advocates a strict good/evil binary between the brothers (Bolshevik brother, good/Nationalist brother, evil).[103]

Dressed in ‘sharovary’, Pavlo walks in an arc among a western dressed crowd surrounded by racing car paths of a busy cosmopolitan street. Pavlo’s promenade also highlights the early quintessential figure of modernist Europe, the flaneur. Prague is presented as a post-civil war refuge for the fleeing ‘bourgeoisie’ and Whites, but also the regrouping Ukrainian nationalists. Dovzhenko pictures these varying trajectories of revolution. Pavlo and the traffic are framed in longshot - points on an motive trajectory. Like Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling in their dadaist film orchestrations of abstraction, Rhythm 21-25 (1921-1925) and Diagonal Symphony (1921), Dovzhenko abstracts object reality into constitutive form[104]. Here, reality is reduced to a few thick black lines and geometric shapes.

|

|

Kazimir Malevich, Suprematic Composition, 1921, Kyiv |

This motif of geometric abstraction recurrs in the ‘revolving’ doors used by the bourgeoisie clamouring to get into Pavlo’s lecture performance. Conscious of Western European avant-garde improvisations that used real objects for abstract form (Leger, Man Ray), the revolving doors convey the idea that the revolution’s momentum is out-of-control.

During the twenties, Dada and Constructivism were prominent in Europe. Moholy Nagy comments,

The Constructivists living in Germany (Theo van Doesburg, El Lissitzki, Hans Richter et al.) called a congress in October of 1922, in Weimar. Arriving there, to our great amazement we found also the Dadaist, Hans Arp and Tristan Tzara. This caused a rebellion against the host, Van Doesburg, because at that time we felt in Dadaism a destructive and obsolete force in comparison with the new outlook of the Constructivists. Doesburg, a powerful personality, quieted the storm and the guests were accepted to the dismay of the younger, purist members who slowly withdrew and let the congress turn into a Dadaistic performance. At that time we did not realize that Doesburg himself was both a Constructivist and Dadaist.[105]

The confluence of these two seemingly antithetical aesthetic philosophies may seem odd. In Zvenyhora’s Nationalist-Suicide performance, there is an analogous Constructivist-Dada convergence. The intertitle introduces the segment with: “The Duke of Ukraine will read a lecture on the destruction of the Ukraine by Bolsheviks. After the lecture he will shoot himself with his own revolver before the eyes of a respectable audience”. Pavlo’s gesture will be violent, Dadaist and destructive. He walks to the podium with an exaggerated step and decorum. The spatial constructions emphasize balance and symmetry. From a clear glass jug, the Duke pours and drinks a glass of water. Envisaging the stage as a dynamic constructed volume, the cubes, cones and abstract shapes create an environment of geometric form. Foregrounding materials of construction and stereotyping Soviet constructivist theatre set design, the stage is reminiscent of Exter’s constructivist designs for Famira[106] or Protazanov’s film, Aelita: Queen of Mars (1924).

|

.jpg) |

||